This is a guest post written by Michael’s wife about her experience working as a doctor at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital on September 11, 2001. They cleared the hospital and waited all day for injured victims to show up, but nobody did. She wrote this about two weeks later.

This is a guest post written by Michael’s wife about her experience working as a doctor at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital on September 11, 2001. They cleared the hospital and waited all day for injured victims to show up, but nobody did. She wrote this about two weeks later.

See Michael’s 9/11 diary here

At first it was a fire.

From the patient lounge on the AIDS/Tuberculosis ward of Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, the prison guard who was there to guard my incarcerated patient announced, somewhat casually, “Hey, one of the twin towers is on fire.” We all looked up, puzzled. One of my co-interns asked “which one?”, but could only remember that the one his mother worked in had the antenna. We went to the lounge to look at the TV, and there was the one with the antenna, a thick, concentrated stream of smoke streaming from a big hole about 3/4 up. He went to the nurses’ station to call his mom.

Patients, family, nurses, and doctors were now all standing in front of the television in the lounge, watching the plume of smoke. Some people went to the window, which, being at the top of a large hospital at the top of Manhattan, looks all the way downtown, past Central Park, the Chrysler Building, and the Empire State Building all the way to Wall Street and the Trade Center. In the mornings, after about an hour of work, I can see the sun rise and glint pink off the Twin Towers, and think, Mike’s down there. Tuesday was a clear day, and we had a great view.

I called Mike, who works on Wall Street, about ten blocks from the towers. He picks up the phone immediately and says “We’re OK.” News is starting to come in. It’s not a fire, it’s a bomb. Some people think it was a small plane that hit the tower. An accident? Someone else asks. No one really knows. Downtown, no one knows either. Mike is trying to email his clients, who work on the 85th floor of the burning building. I tell him I love him and we hang up.

I try to go back to my regular morning business. I find my med student. This morning I’m going to teach him how to put in iv’s. I get the stuff together, and we start to set one up, using the bottom of a tissue box as our first iv-needing victim. Then there’s a collective gasp from the lounge. A plane just hit the second tower. More people rush to the window. We run to the television or the window where you can see both towers, smoke pouring from the top of them like blown-out birthday candles. My friend O—, whose mother works in the tower with the antenna, looks pale. An announcement comes over the speakers calling all of the heads of department of the hospital to an emergency meeting. My resident shows up, who hasn’t heard any of it. I explain that it looks like two planes crashed into the World Trade Center. “By mistake?” he says. “I don’t think it’s an accident,” I say.

Things start to happen very quickly. One of the second-year residents shows up to tell us that the hospital is in disaster mode. I am on call; this means that I’m going to be admitting people into the hospital today. I’m told to expect to be busy for the next few days. All elective surgeries and procedures are cancelled, and the operating rooms will be open and ready for any injured. We should try to discharge as many people as possible from the hospital to leave more beds open for the wounded. Any extra doctors on non-critical services are being pulled to help triple-staff the emergency room.

Then I get paged by my brother-in-law. I call back and after two or three tries I get through. My sister-in-law, Kim, gets on the phone to find out if I’ve talked to Mike. I say that I did, but that was before the second plane hit. Kim says that Jim, Mike’s brother, really thinks that Mike should get out of downtown as soon as he can. She sounds scared. I try to call Mike’s office, but all the phones are down. In the meantime, I’m trying to talk over my patients with my resident and find out if we can get any of our patients out of the hospital. We come up with a list of three people who can probably leave. Mike’s sister in Boston pages me. She wants to know if I’m OK and if I have heard from Mike. I try to call Mike again. I get his co-worker, Nadia, who says that she can’t find Mike, that she thinks he may have left the building. I feel like she just punched me in the stomach.

Then I’m paged by the MAR (medical admitting resident) about my new admissions. They are trying to get as many people as possible out of the ICU’s and out of the emergency room. She tells me about three new patients, all of whom are on the floor and waiting for me to see them (usually you find out about patients you will be admitting long before they actually arrive to your care). One of them is coming out of the ICU because they need a bed but is still pretty sick. The MAR says I should try to check on him soon because he’s “not that stable.” That’s doctor-speak for dying more quickly than slowly.

We start rounds. My attending physicians seem relatively unaffected by the whole thing and we start rounds like it’s a regular day. Except for the fact that we can still hear people yelling news from the patient lounge, and the TV blaring with voices that we can’t quite make out. For the next two hours, we sit in rounds, listening to patient presentations, and my attendings have an academic discussion about treatment of pneumocystis pneumonia. I don’t hear any of it. The only thing that is in my mind is that Mike left his office and no one has heard from him. And next to and towering over Mike’s subway stop is the World Trade Center.

I get paged again to Kim and Jim’s number. But all the hospital phones and cell phones are down. I go back to rounds, where the discussion continues. I get paged again, so I leave rounds and go down the hall to where there are pay phones. There are people in the hallway crying and a man on the phone next to me saying “Its OK, its OK, its OK,” into the receiver. I call Jim and Kim’s number and get their voicemail. I go back to rounds. Ten minutes later I leave rounds again, go back to the same payphone, and get their voicemail again. This time I leave a message, telling them to please have Mike page me if they hear from him. I tell them that I love them and I hope they are ok. I’m sure this is the first time I’ve every used the word love with my in-laws.

The resident who is transferring one of his patients to me comes in to rounds to tell us about her. But first, he tells us that both of the towers have fallen. “You mean collapsed to the ground?” someone says. Everyone looks numb, but no one else says anything. We go on. All I can think of is Mike. Both my feet seem to have fallen asleep as I realize that I would never be able to do any of the things I do without him. I could not be a doctor, could not continue my internship, could not be a good friend, could not be myself. We’ve been together for six years, married for three months, and it dawns on me that what we have become is so much better than who we are individually. I think about what it would mean to lose that. A tear hits the page in front of me and I discover I am crying.

I leave the room, without even being paged first– a giant break in attending rounds protocol, so much so that I actually pretend that I’ve been paged, looking down at my beeper at a number I can’t even see. I go back to the same payphone. I pick up the phone and miss-dial the number twice before I can put the right numbers in the right sequence to call Kim and Jim. Kim picks up the phone, she says that Mike is there, that he and Jim went out to try to get cash out of an ATM. They are all ok. Mike and Jim come back from the store and Kim puts Mike on the phone. Hearing his voice makes me realize how tired I am and how much I want to be with him.

Mike asks if I can leave the hospital. They want to drive out of the city to someplace safe and want me to come, but all the roads are flooded with people trying to do the same. Mike starts to tell me about what it was like leaving downtown but breaks down. Later, he tells me how he left Wall Street and traveled within two blocks of the towers to find a subway to take him uptown. He tells me about seeing some people fall out of the towers, and some people jump, holding hands. How thousands of other people were just standing, out in the open, watching, unable to move or look away. He wants me to come home soon. I tell him I don’t think I can leave the hospital for the next few days. I tell him I love him. I have to wait to stop crying before I can go back to rounds.

Rounds are ending, thank god, and the rest of the day passes in a daze. I am busy, frantically rushing to get all my work on the patients who are in the hospital already done so that I can be ready when more arrive. We keep waiting for people, keep asking if anyone has shown up yet in the emergency room, if ambulances have brought up any survivors. The answer is always no. The smoke plume from downtown shifts directions, and the whole hospital starts to smell like smoke. “Is something burning?” one of my patients asks me. “Yes,” I say, “Downtown.” Televisions in every patient room are on, blaring, with news from the disaster. My friend O— hears from his mom at around 1PM. She was evacuated safely.

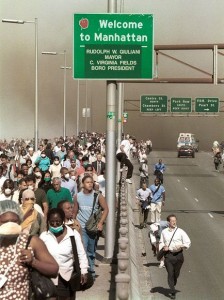

We can hear helicopters and planes screeching overhead, ambulances and firetrucks below and see all the traffic stopped going up the West Side Highway. There is a bomb threat on the George Washington Bridge, which is a few blocks from the hospital. We all eye it from the windows as we go about our day. All day, as I come across people, the greeting is always, “How are you doing? Do you know anyone down there?” We are all trying to both get our work done and call relatives, friends, anyone we know who might have any reason to be downtown. As we work, our friends are streaming out of downtown, ash covered, heads down, not looking back, a gray pilgrimage pouring over every bridge, up the FDR and West Side Highway away from the disaster. There are no cars, so they walk on the five-lane highways and avenues, and soot drops on them as they go. From the hospital, we can look down and watch them pour over the GWB, having walked the length of Manhattan in their dress shoes and suits to go home to their families in New Jersey.

Mike actually got on the subway before the buildings collapsed, before the subway stopped running. So he came up to midtown on a train of people, half of whom knew what was happening and half of whom had been on the subway since Brooklyn and were still living in the New York City where none of this was possible. They only made it to midtown though, and then Mike ran though Central Park, leaving dusty footprints in the jogging lane, to Kim and Jim’s apartment on the upper West Side.

At one AM, September 12th, I’m finished with all my work. I haven’t gotten any more new admissions since those I heard about in the morning when we first went on disaster mode. All of my patients are “tucked in” for the night. But no one is sleeping. The patients on our service, many gaunt with AIDS and haunted by traumas, past and present, are wandering the halls of the ward, staring at each other as they pass by, iv poles in hand, walkers pushed in front of them. Roommates who have ignored each other in spite of being five feet apart through their entire hospital stay are talking to one another.

The ER is like a ghost town. Eerily silent, yet full of doctors, nurses, social workers, many of whom just showed up at the hospital that morning to see if they were needed. The surgery interns are sitting on empty gurneys, swinging their legs over the side and waiting for patients who aren’t coming. Occasionally someone will say “I can’t believe it.” Or “its like a movie.” The only loud sounds are the telephones, which the social workers are answering, telling caller after caller, all in tears, that we haven’t seen their wife, son, partner, mommy, that they haven’t been sent to our hospital.

Downtown, we hear that they set up a triage center and the building fell on it, killing all the emergency workers, including the disaster coordinator for the state of New York. Then they set up another one and then rubble fell and destroyed it as well. I keep thinking that if I hear anything worse than what I’ve just heard I will break down, be unable to do my job. But then I do and I just get more numb. I desperately want someone to hug me so that I can just cry and stop pretending to be a doctor.

I go to the resident lounge to find out what I should do next. All day, I’ve actually looked forward to finally being able to do my part for the people caught up in this nightmare. But when I get to the lounge it is full of residents watching TV with tears in their eyes. I ask one of the chief residents what I should do next. There is nothing. No survivors are beating down our doors. The thousands of people who walked out of the financial district, looking like ghosts covered with white ash, don’t need our help. Like my husband, they are home with their families, trying to put words to what they saw. The other thousands who were still in the buildings at the time of their collapse are beyond our help. They tell me to go home and sleep.

So, at 1:30AM, I take a gypsy cab from the hospital to my apartment. I share it with my friend R—, who spent the entire afternoon looking for her grandmother who works on the forty-fifth floor of tower two. It turns out that her grandmother had been late to work that day, which saved her life. She was in the lobby when the plane crashed into her tower, and was able to get out safely but had smoke inhalation and couldn’t contact her kids (or grandkids) until around 7PM. On our way home we pass a large FedEx truck, surrounded by police cars, firemen, and dogs. As the cab slides silently past, I am sure that it will blow up. It doesn’t.

I crawl in to bed with Mike at 2AM. He is not asleep. I get the hug that I’ve needed all day, and say a quick prayer of thanks that I, unlike so many people tonight, have someone to come home to. Then I feel selfish for thinking that. Mike has fallen asleep when a truck rumbles down Amsterdam and he awakes with a start. “I thought it was a plane,” he says. At four AM I get back up to go back to the hospital. I cry as I dress, and step out of my door into a ghost town, where nothing is open, there are no little tin coffee carts on my street to sell me breakfast, and no cabs. I take the subway back to the hospital. There are very few morning commuters. At the top of Columbia Presbyterian, my friend Jeff and I walk to the window and look downtown. There is a hole in the sky, and below it a red glow. Smoke pours into and out of that hole in the sky. The Empire State Building, always dwarfed, looks huge and vulnerable. I am afraid for it.

The next few days are still a blur. I spend all day Wednesday in the hospital, where we still have hope for caring for some of the victims as the digging begins, and again I am sent home early in the morning on Thursday because there is no one to fix. I sleep four more hours that night, and then my schedule changes, so that on Thursday evening I leave the hospital before it is dark for the first time in a week. My blurry eyes look around at a different city. On the street, there are flags in every window. On the subway, people are deferential, and try to give everyone some personal space. In shops, on the sidewalks, and street corners, people speak quietly, and it is not uncommon for someone to be crying as they go about mundane tasks. Church, temple, synagogue and mosque doors are all flung open, with signs that say come in to pray in many languages. Many shops are closed, and on those shop fronts, on bus stop overhangs, and on the sides of buildings all over the city are the missing signs. The faces of people who didn’t walk out. What they were wearing, how tall they are, how much they weigh, which tower, what floor they were on.

Over the next week, we, the City of New York, the New Yorkers, Gotham, learn that we actually are one group. That though we are the most diverse city in the world, we do belong to something. That something is terrible and tragic and stunned, but at least we aren’t alone. We greet friends and acquaintances we haven’t seen yet with “How are you doing. Did you know anyone down there?” When the phones are working we continue the calls to friends and colleagues who we haven’t heard from. We flinch every time we get an answering machine. We go to Union Square and light candles in front of the pictures, the poems, the paintings that are our response to what has happened to us. We clean our apartments and sweep up the white dust that seems to be everywhere. We look up into the sky with dread every time we hear an airplane, we walk quickly past tall buildings, we jump at loud noises that were part of regular life in Manhattan just a few days ago.

Now, weeks later, I cry when I read the paper. Mike, who sat at home with nothing to do the first two days after the disaster, has returned to work to watch the market fall and fall and his co-workers go to funeral after funeral. He came home for the first week with his clothes smelling like smoke. He is less on edge. We are more able to talk about things other than what happened that day. But we still don’t have a name for it. Its funny, but no one in New York seems to refer to it as the attack, and the bright logos and big adjectives used by the news networks seem unbelievably inappropriate in our gray, solemn city. We call it “Tuesday” or “the 11th” or “the disaster” or just “what happened.” We still cannot really describe what it is like to wake up to a world where none of the rules you thought applied to your life, or your safety, or your ability to see the people you saw today again tomorrow, work anymore. Our eyes have been opened. We look at the people we love now and realize that every day with them is a blessing and we should live with the knowledge that it could be our last.

Also See: Michael’s annotated diary from 9/11

Post read (9121) times.

Ok, so it’s no secret I’m pretty sweet on SIGTARP, the Norse God of Financial Accountability.

Ok, so it’s no secret I’m pretty sweet on SIGTARP, the Norse God of Financial Accountability.