Every once in a while I read a finance article that sticks in my head and never goes away. An article about the historical intersection of debt and the United States from the New Yorker from four years ago by Jill Lepore is just one of these.[1]

Every once in a while I read a finance article that sticks in my head and never goes away. An article about the historical intersection of debt and the United States from the New Yorker from four years ago by Jill Lepore is just one of these.[1]

The USA of IOU

Jill Lepore’s article explains that in many ways the United States was founded of the debtors, by the debtors, for the debtors.

We know from English literature that the United States represented a fresh start for insolvents from the lower and upper classes, which makes sense when we learn that both Dickens’ father went to debtor’s prison and Trollope’s father fled England to avoid it.

What I didn’t know is that as many as two-thirds of Europeans arriving in the Colonies were debtors, paying their way as indentured servants. The colonial governments of Virginia and North Carolina for their part, eager for laborers, passed incentives by promising 5 years’ worth of debt protection. The founder of Georgia, James Oglethorpe, specifically started the colony as a debtor’s refuge in 1732, as an alternative to English debtors’ prison.

Lepore makes the interesting comment that Founding Fathers Jefferson and Washington were so up to their necks in debt to London bankers that the Declaration of Independence from England not only served democratic Enlightenment ideals but also their own balance sheets.[2]

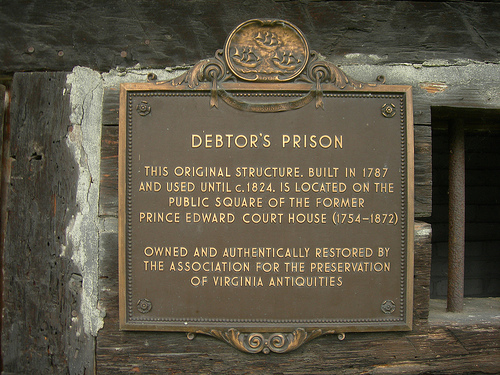

Debtor’s prison

Before reading Lapore’s article I had no idea that the English tradition of locking up debtors in prison jumped the Atlantic and came to the American colonies and the young United States. Debtors through colonial times and the first 40 years of the Republic routinely got locked up in brutal prisons, – often for very small amounts. There the debtor would stay, half-starved and dependent upon alms from passers-by, until someone – usually a relative – paid the debt.

New York became the first state in the nation to outlaw debtors’ prisons in 1831, paving the way for other states to follow suit.

Debtors’ prisons largely predated proper bankruptcy law, which makes sense as bankruptcy would always be preferable to prison.

Bankruptcy for Traders vs. Everybody Else

You are not going to believe this[3], but in the 1800 to 1830 period, financial traders typically received preferable treatment, by law, over everybody else, when it came to insolvency.

If you were a stockbroker in 1800s Wall Street, for example, or you engaged in financing merchandise shipping and trade, or trading in agricultural commodity futures[4], you could declare bankruptcy if the business went awry. But, if you were not a financier, you had no way of getting clear of your debts, and you might face debtors’ prison.

In essence when debts became overwhelming, Lepore explains, a bankruptcy law in 1800 allowed financiers to declare bankruptcy and receive a fresh start, freed of their debts. Presumably lawmakers justified this disparity through a logic similar to today’s “Too Big To Fail” principal. If the brokerage houses in turn of the 19th Century Wall Street couldn’t work through their financial distress, well then my goodness, what would happen to the economy????[5]

Since the bankruptcy law only applied to traders, everybody else was liable to be thrown into debtors’ prison. Indefinitely, in fact, until their debts got paid. Not until 1841 did Congress pass a permanent bankruptcy law so that ordinary folks could declare bankruptcy in the event of insolvency.[6]

So, if you were wondering whether the bailout of Wall Street in 2008 while Main Street suffered represented the nadir of financial inequality and injustice, you’d be wrong. Early 19th Century injustices were even worse. There, doesn’t that feel better now?

[1] Here’s a Scribd link to the article as well.

[2] Before reading Lepore’s piece I knew about the historical train of thought that the Founding Fathers were greatly motivated by selfish private interests, such as keeping taxes low and protecting their own private property, something that British sovereignty increasingly impinged upon in the years leading up to the Declaration of Independence. As a recovering banker, however, I find the we’re-up-to-our-necks-in-debt-let’s-cut-ties-with-our-bankers argument plausibly intriguing. I’m sure Jefferson and Washington were great guys and all, but any time you can simultaneously establish a radical new experiment in non-Monarchical government based on Enlightenment ideals and wipe out your personally huge debts at the same time? Wow, I mean, that’s a two-for-one. You kind of have to do it.

[3] Yes, that’s sarcasm.

[4] Yes, the concept and use of commodity futures are not hundreds, but thousands of years old.

[5] Does this sound familiar to anyone?

[6] Lepore relates the story of a clever insolvent who found a loophole in the bankruptcy law of 1800 that offered unequal treatment between traders and everyone else. With extraordinarily large debts that had previously landed him in jail, her hero John Pintard managed to get a temporary reprieve from prison through a loophole in the debtors’ prison laws. He took out an advertisement in a newspaper that he was doing business as a stock broker. Pintard then traded a single stock, pocketed the fifty-eight cents profit (later donated to charity), and filed for bankruptcy as a trader.

Post read (9573) times.