First, my confession

Before this week, I had never watched Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life.

I know I should not admit this in a public place.

I know this will land me on the Un-American watch-list with the data-miners at the NSA faster than shouting my support for Al Qaeda in Times Square.

But there it is, the cold truth. I had never watched It’s a Wonderful Life.

Well, nothing unites the themes of Christmas and suffering bankers as well as this movie, so I sat down to watch it with my eight year-old this week.

Little did I know I would soon be writing a blog post about a) Bank runs and b) The origins of Bankers Anonymous.

***SPOILER ALERT***

For other people who have never seen It’s a Wonderful Life (like me, living under a rock, clearly hating America’s freedoms) I will divulge plot points of this movie that’s played constantly on TV since 1946. Ok, thank you.

***END SPOILER ALERT***

Ready for snark

I settled in to my couch with a bag full of Harry & David’s chocolate caramel popcorn (aka Yuppie Cracker Jack) in one hand, and a metaphorical pen full of snark on the other. A syrupy-sweet movie about finance that everybody loves? I knew I was going to hate it.

The first scene certainly opens up the film to snark. The starry night, with a couple of disembodied voices, looks worse than an iMovie my eight year-old would make on a bad day.

With those kind of movie production values I’m going to slash through this movie faster than a pint of dulce de leche on a Friday night home alone.

But then I started to relate to the George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) character

He doesn’t dream of being a banker. He’s eager to travel, to have adventures, to break away from his hometown.

In fact, he’s really not a good banker at all. He is what I call “improvident and cheerful,”[1] and runs the Bailey Building and Loan Association nearly into the ground a few times as a result.

Bailey’s also no saint. When the ultra-capitalist Potter tempts him with a job offer to work for The Man, Bailey nearly goes for it. Even knowing Potter’s unethical behavior, Bailey wants more money to provide for his family and to gratify his ego.

As a father and husband Bailey takes his blessings for granted. He complains to his wife about his drafty old house, with a faulty wooden banister ornament. He resents his young children for making demands on his time, or for practicing the piano loudly as he seeks peace and quiet at home.

When the children in Bailey’s household become especially annoying, I silently looked daggers at my eight year-old on the couch as if to say, “See how you are?” She just smiled back sweetly and continued making compound interest calculations on her notepad. (Good girl.)

I sympathized with George Bailey’s woes. I also started to appreciate the movie’s solid presentation of a few key banking concepts.

Solid banking concepts – fractional reserve lending and bank runs

A) Fractional Reserve Lending

In the first bank run on the Bailey Building and Loan Association – on the eve of George Bailey’s honeymoon – we learn the basics of fractional reserve lending.

Banks never actually hold your money in a vault, as George Bailey explains, but rather they lend it out to others.

One household’s deposits, Bailey explains to his frightened customers, are lent as a mortgage for “Joe’s house, that’s right next yours, and the Kennedy house, and Mrs. Maklin’s house, and a hundred others.” At any given moment, most deposits do not remain in the bank, or even in liquid securities or cash. Instead, banks these days hold about 8 to 10% of their total funds in accessible funds, and try to loan the rest out at a profit.

Because all banks, just like the Bailey Building and Loan Association, operate on a fractional reserve lending policy, all banks also run the risk of a bank run.[2]

B) Bank Runs

When Potter calls in a large loan, and probably as a result of a Potter whispering campaign, the people of Bedford Falls lose confidence in Bailey’s bank. When the depositors of the Bailey Building and Loan Association fear for their accounts, they demand their money in full, an impossibility for a fractional reserve lending bank that isn’t covered by depositor’s insurance.

We get a sense for the panic that sets in when people lose confidence in fractional reserve lending. Banks that are not too big to fail simply cannot meet the demands of depositors if they all want cash returned at the same time.

Rock Bottom

George Bailey’s faults warmed me up, the accurate banking concepts earned my trust, and then Bailey hit rock bottom and I am completely captured…

On Christmas Eve morning, the unthinkable happens. Bailey’s uncle misplaces $8,000 just as the bank examiner for the Bailey Building and Loan Association arrives. The bank, always thin on capital, will go under without the $8,000. Bailey’s nemesis Potter – who surreptitiously pocketed the money himself – alerts authorities to the missing money, leading to a warrant for Bailey’s arrest.

The stress breaks Bailey, pushing him to reject his family, drink too much, crash his car, and contemplate suicide.

Suddenly I realize that I am George Bailey.

My George Bailey moment(s)

My own ‘bank run’ and business failure played out over a longer period of time than one night, from the Fall of 2008 until the end of 2011.

Up until this point with Bankers Anonymous I haven’t wanted to share the story of my investment business, nor the origins of this blog, because nobody cares for a banker pity-party. Many people suffered far more than me in the Great Recession, and I cannot compare my own losses to theirs. But the pop-culture phenomenon of It’s a Wonderful Life – the entire plot hinges on a banker pity-party! – encourages me to at least share my story.

I started my investment company in 2004, and it began to grow in earnest in 2006. When the jitters of the Summer 2008 turned into the wholesale panic of the Fall of 2008, a majority of my investors requested their money returned.

Two of my institutional investors, both “Fund of Funds” firms[3] requested their entire investment back, each request within a week of each other. It turns out, both Fund of Funds clients had been wiped out of capital by redemption requests from their own investors. Simultaneously, a few of my early individual investors also asked for capital returned in the Fall of 2008.

Although I didn’t operate a bank, my nascent fund was hit by a “bank run” just the same. Too many folks needing their money back all at once meant that other investors demanded their money back, just to avoid being left holding the bag. Just as depositors do with the Bailey Building and Loan Association.

My remaining investors, many of whom were friends or family, didn’t ask out of the fund, either out of their belief in me or an unwillingness to abandon a sinking ship. But by hanging on to these remaining investors I would end up leaving them with illiquid pieces of a dying fund. By the end of 2008 I realized that to be fair I needed to return money to everyone in the fund at the same time.

The fund manager or banker, subject to a bank run from his investors, rarely seems like a sympathetic character in popular culture. If I hadn’t lived it myself, I could easily think that the person unable to meet immediate demands for cash was irresponsible with money, or an idiot, or a crook.

Well, I’m none of these things.

And George Bailey’s predicament hit home for me.

Unlike George Bailey, I couldn’t stop the bank run.

Not suicide, but a kind of living death

I never spent a George Bailey Christmas Eve getting drunk, crashing my car, and looking over a bridge contemplating the end. I’m relatively lucky that I’m not really wired like that.

Instead, I spent three years, from 2008 to 2011, thinking about my own business failure. First, I made the phone calls to say that you could not have all your money back right away. Later, I made the phone calls and wrote the letters to say that you should expect losses now, and your money remains at risk of more losses over time. I liquidated assets as best I could, knowing the range of outcomes was between mildly crappy and terrible, depending on how well I did. Three years of phone calls and letters to people who had believed in me, keeping them updated on my attempt to turn a smelly dung heap into a useful compost pile.

Three years, walking around, feeling like an fool.

A few examples of my mindset

Just about every waking hour, and many hours asleep, I returned to the ‘bank run’ on my fund, and the subsequent losses for investors, and the loss of my entrepreneurial dream.

Having dinner with my wife. How do I look my investors in the eye again?

Playing with my growing daughter or holding my newborn. I can’t believe I had to shut down the fund. How could I have fucked it up so badly?

Moving to a new city, finding a wonderful home and neighborhood with compatible friends. Why is a smart guy like me so stupid? Do they know what a fucking failure I am? The important thing, of course, is to not let anyone in on my failure.

What do you do for a living?

Whenever any new acquaintances asked me during those three years about what I did for a living, I would mumble something vague about ‘winding down my fund, trying to figure out the next step.’ Something in my tone no doubt implied I didn’t seek any follow-up questions. My mysteriousness probably gave the mistaken impression that I had plenty of wealth and didn’t really worry about ‘working for a living.’[4]

On the contrary, I obsessed about ‘working for a living.’ How come I failed to provide for my family? What could I possibly do next? I was too gun-shy to start another investment company. Yet I found facile objections to all other professional directions as well.

Occasionally someone close to me would point out how blessed my life seemed. I would smile and try to nod in agreement, but inside I certainly didn’t feel blessed. What about my business failure? Aren’t you forgetting about that? Because I’m not.

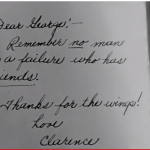

An inscription to make me weep

At the end of the movie, George Bailey’s guardian angel Clarence gives a book to Bailey, with the inscription:

Remember no man is a failure who has friends.

George’s wife Mary saves him by appealing to the townspeople of Bedford Falls. Remind George of your friendship, she urges, and they bail him out financially, as well as spiritually, expressing their love for him on Christmas Eve.

At that point in the movie, cynical me is blinking back tears and snuggling closer to my eight year-old.

After watching me dwell daily, even hourly, on my business failure for three years, my wife took a page from the Mary Bailey strategic playbook.

For my fortieth birthday she asked my closest friends and family to each write a letter expressing appreciation for my friendship. The result, presented to me in 2012, stunned me. One after another[5] after another[6] after another[7] stunned me with love[8] and thoughtfulness.[9] You mean, despite my failure, I am worthy of love?

It’s A Wonderful Life captures this kind of moment on film.

These letters’ effect on me

First, of course, waterworks. Stomach-churning, ear-roaring, and eyesocket-wringing tears.

Second, I had the letters bound into a book. What’s the one physical possession I would grab and take underground with me when the zombie apocalypse begins? This book.

Third, I met with a web-designer friend that week about starting a blog called Bankers Anonymous.

Discovering the Bankers Anonymous motto

At the beginning of the first bank run, as he steels himself to save the Bailey Building and Loan Association for the first time, George Bailey glances at a picture of his father. An inscription next to his father’s photograph reads:

All that you take with you is that which you’ve given away.

Well, I started Bankers Anonymous eighteen months ago to try to give away some financial knowledge I have gained.

Engaging in a dialogue about finance seems the best way I can think of for preventing the next great bank run, the next Big Crash. If we better understand Wall Street and how it’s regulated, maybe we won’t repeat the same errors.

If we better understand our own personal financial situations, maybe our households won’t be so devastated by the next Great Recession.

Those ideas are what I’ve been trying to give away, and in the process I’ve been able to take with me so much. Every time a reader comments on my posts or sends an encouraging email, I feel the truth of that inscription at the Bailey Building and Loan Association.

If you celebrate Christmas, and you find yourself begrudging the trip to the mall to acquire an ugly tie for your colleague or the must-have Skanx doll for your pre-teen daughter, all I can suggest is a return to that inscription from It’s a Wonderful Life.

“All that you take with you is that which you’ve given away.”

Peace to All.

[1] Bonus points to anyone who recognizes where that phrase “improvident and cheerful” comes from – without referencing The Google, of course. If you need a hint, I’ve linked to the book here.

[2] All banks except banks covered by deposit insurance such as provided by the FDIC in the United States. But that coverage did not come into effect until June 1933, presumably after the scene of the initial bank run in It’s a Wonderful Life, which probably takes place in 1932 or early 1933.

[3] A “Fund of Funds” pools together investors such as Endowments or Foundations or individuals and in turn allocates their capital to managers like me. The problem is, and was, that the Fund of Funds do not control their own capital. When the original endowment, foundation, or individuals asks for money back, the Fund of Funds requests a redemption from the manager. See related podcast/post “What the $%& is a Fund of Funds?”

[4] Nope, not wealthy. The reality is that my wife is a doctor, and we live in a city that’s affordable on one good salary.

[5] “You’ve made it easy when I’ve needed something and returned the favor of needing things from me, which is no small thing.”

[6] “You and your family make me very very happy, and I know you will do so until I die.”

[7] “You are like a brother to me.”

[8] “You have at age 40 what people of my generation traditionally have worked for their whole lives.”

[9] “Give yourself the gift of being able to fail and struggle and shine and succeed, often simultaneously.”

Post read (12997) times.