I enjoy and look forward to your advice every week. I am about to do as you (and a lot of other smart people) recommend and move our investments to several diversified equity index funds. My question: would you still suggest no index bond funds for someone in our age bracket? I am 71, and my wife is 65. We have a comfortable railroad pension and this year I started my Required Minimum Distribution (RMD.) We have modest money to transfer ($145,000) from Morgan Stanley to I was thinking Vanguard.

–Bob in San Antonio

Thanks, Bob for your question, which refers to my recent exhortation that 95% of people should have 95% of their money invested 95% of the time in diversified 100% equity index funds, and never sell.

The quick answer to your question is yes.

I still would give you the same advice, although with a few caveats. The first caveat of course is that this advice is free, and you get what you pay for!

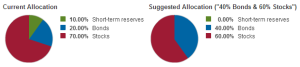

Also, I don’t know your full situation so I’ll make base-case scenario assumptions and you can fill in the details. The key to the choice to remain 100% in equities (instead of bonds or some other fixed income) is your time horizon. Above a 5-year time horizon (my minimum for ‘investing’) then people should be in diversified equities rather than ‘safe’ bonds or savings.

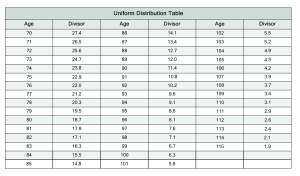

Now, you are 71 and your wife is 65, which puts your expected remaining lives (according to this Social Security actuarial table) at 13.4 and 20.2 years respectively. Given the way probabilities work, you should want to maximize your investment account for 20 years or longer, at least to support your wife (who is likely to outlive you). If you have heirs, your time horizon will be longer than even 20 years, and might really be measured in many decades.

I’m assuming all along that you will not have to sell the funds in your account, and you won’t be spooked by market volatility, which can and will be substantial over the next 20 years. At the worst moments, sometime in the next 20 years, risky assets like stocks could lose 40% of their value from their peak, the sky will look like its falling (it won’t be), and you have to know yourself well enough to know whether you could stomach that kind of volatility without selling.

Pensions & Social Security act like a bond anyway

Another factor specific to your situation that makes 100% equities even more acceptably prudent is that your railroad pension looks and smells and acts like a bond. Meaning, it probably pays the same amount every year without any volatility, or maybe it adjust slightly upward for cost of living changes. Social Security works the same way. The fact that a huge portion of your income is fixed income and bond-like and safe and snug should make you even more comfortable with the idea that you can remain exposed to volatile equities.

Without your pension & social security – If you had only your equity portfolio to cover your expenses – you might be forced to sell some equities to cover your costs at an inopportune time, and then 100% equities would be less of a slam dunk.

Adjust for RMD?

Speaking of selling, the RMD could change your decision (and my advice) slightly.

You know you’ll have to withdraw some required minimum distribution (RMD) each year, based on the IRS rules and your expected lifespan. A reasonable case could be made that you should keep at least one year’s RMD in cash, since you know your time horizon on that amount of money is very short. Many reasonable people might advocate a few years’ RMD in cash for the same reason.

I think its just as reasonable, however, to decide instead to keep the account fully invested in 100% equities, betting that equities will outperform bonds more years than not, and that your twenty year time horizon still justifies the decision.

The deciding factor between these reasonable scenarios, in my mind, is how ‘comfortable’ the ‘comfortable railroad pension’ really is. If your lifestyle costs are fully covered by the pension, and the retirement account subject to RMD rules is just extra money, then you can think of that investment account as intergenerational money. If you have heirs or a favorite philanthropy to pass money to, for example, then the time horizon for your account can be measured in decades, and you should undoubtedly stay 100% in equities. I’m confident that with a 20 year time horizon or greater, there will be more money in the end via equities than there would be if you invested in bonds.

With plenty of interim volatility, of course.

Good luck!

Michael

Please see related posts:

Hey Fiduciaries: Is It All Financially Unsustainable?

Stocks vs. Bonds – the probabilistic answer

Post read (1536) times.