Podcast: Play in new window | Download

I recommend listening to the audio version of this interview…It’s the best part!

Michael: Hi, my name is Michael, and I used to be a hedge fund manager.

Peter: My name is Peter Kovac, and I’m the author of Flash Boys: Not So Fast.

Michael: Flash Boys: Not So Fast came out recently on Amazon[1] and is of course available, and is a response to Michael Lewis’ book named Flash Boys in which I’d characterize you as disturbed enough by his version of high-frequency trading or algorithmic trading to try to correct the record, which you have done, and I have reviewed. I just thought it would be interesting if we could talk through some of the issues.

I’m assuming for the purposes of this that people are familiar with the broad outline of Flash Boys. The hero of Flash Boys is this guy Brad Katsuyama and he doesn’t end up as a hero in your retelling. I describe him – kind of paraphrasing your words – as he’s either a dupe for not really understanding how equities trade in 2012, or he’s mostly a salesman. Is this a correct characterization of your view of him, or am I being overly aggressive?

Peter: Michael Lewis kind of channeled the entire story of Flash Boys through him. And so I’m really responding to the way that Lewis has portrayed Katsuyama. In Lewis’s portrayal, it does kind of seem like he’s a dupe. He seems like the guy who is the head of a major equities desk, yet apparently is unaware what the fee structure is across the market and he has to Google it. He makes very large trades that have huge price impact on the market, and then is unable to explain them. So it really seems to me like it is Michael Lewis who set him up this way and I’m just responding to how he’s been portrayed in the book.

Michael: Okay, I’m not an equities guy, so I learned stuff from both Michael Lewis’s book about how the equity market does or might work, and I learned stuff from your book about how the equity market does or might work. I’m assuming lots of people listening to this know even less than me. But what’s the traditional role of a guy like Katsuyama or a legacy Wall Street equity trader? Can you describe that a bit before we get to what is “algorithmic” or how HFTs or high-frequency traders get involved?

Price Impact

Peter: Sure. Let me describe specifically the role that Lewis has put Katsuyama into here, which is to take a large order a client has, and the client says this order is too large for me to handle myself. I don’t have the specialized expertise. I don’t know how to put that order into the market, and not create a huge price impact. Price impact is a really fancy way of saying what you learned in Econ 101.

In Econ 101 you learned that if you have a big change in supply or demand it’s going to affect the price. And so if you have a really big order you want to place in the market, obviously if you’re going to be selling a lot of shares, the market is going to drop in price as you’re selling those shares. If you’re buying a lot of shares, the demand is increasing and the market is going to go up.

If you aren’t doing this every day of your life, there’s a chance you’re going to screw it up and not do it as well as it could be done. The function of a trader like Katsuyama in Flash Boys is to take some institution or individual’s large order, and as Lewis says, work on it for hours in the market to try to put a little bit of it out now, a little out later, trying to minimize the impact on the supply-and-demand dynamics so that way you can get a price that’s fairly reasonable.

Michael: Okay, so we would call that maybe block trading by Wall Street. They have a big block of shares they need to sell into the market without moving the market. And he found or at least as Lewis describes he could no longer do that in 2011 or 2012 when he’s reporting on this story, because prices react extremely quickly, in ways that suggest there’s some kind of conspiracy or the markets are not as they a ppear when he tries to trade. Is that an accurate description of Lewis’s version?

Peter: I think so. I think he makes a couple of trades and he sees the market reacting to his trades. Happy to go into those trades. He kind of explains why it’s very reasonable the way the market reacted. But he sees the market react to those trades, and then suddenly instead of being the master of price impact, the master of trying to work these orders over many hours, he says I’m the victim of this price impact. He looks to blame someone.

Michael: Can you tell me in your words what role high-frequency trading firms – because that is your background – interact with somebody like Katsuyama or the rest of the market?

Market Makers

Peter: I can speak to how my firm would have interacted with him. My firm was an electronic market-making firm. What that means is at any given moment we stood ready to buy and to sell any particular security. Whenever you say I want to go out and buy shares of IBM, you may have wondered “It’s funny that when I go out to buy some shares of IBM there’s someone out there who wants to sell them to me at the exact same time. That’s very convenient.:

The reason there is, is there’s a function in the market called a market maker. That person’s or firm’s job is to provide those prices on a continuous basis. And the way market makers make money is if they’re saying we’re going to buy shares of IBM at $164 and we’re going to sell them at $164.01. Then if the market doesn’t move all day long, and equal numbers go and buy and sell, then I’ll make a penny every round trip. That’s how they make their money.

Someone like Katsuyama who then comes into the market and says today I have to buy three million shares of IBM will place an order in the market to buy and we would have orders in the market that are willing to sell. So when his orders come into the market to buy, they would interact with our sell orders. We would never know we were interacting with him. It’s completely anonymous. We would never see his order. We would never know how much he wanted. We would simply get a report back telling my firm you placed an order saying you were willing to sell 10,000 shares. And someone has bought 10,000 shares from you.

We might say great, you know what? We’re going to place another order to sell 10,000 shares because that’s what we do. We put in another order to sell 10,000 shares and then maybe he comes back again and buys 10,000 shares from us. He would be doing that throughout the course of the day, from us and many other firms who are market makers. By the end of the day he has completed his transaction, and hopefully we were able to buy those shares back at a slightly lower price. And we didn’t lose our shirt on this whole transaction.

Michael: I’m familiar because I sat on a trading desk of a bond desk, which is not the same as stocks, but the way the bond desk works is just as you’re describing. We’re trying to buy it at one price and sell it, it being the bond or the stock or the security, slightly lower than where we sell it. And we don’t have a fundamental view on whether that share or that bond is going up or down. We’re just trying to make a tiny difference between where we buy it and sell it. That’s what I understand is a market maker.

I think that you’re describing that what you do is basically the same thing. Although in Lewis’s telling of it you’re doing something fundamentally different. Maybe that’s kind of the heart of the difference between Lewis’s version of high frequency trading and your version. Am I getting that right, that what you’re describing is exactly like a faster and narrower spread basis, but it’s exactly like what I witnessed and participated in, as a bond trading market-maker. Is there anything fundamentally different about what you guys are doing?

Peter: Not particularly. One of the differences is that in the US equities market, unlike the bond market, there are even more constraints on the price that anyone can transact at in the market. For example, in the bond market different brokers might give you different prices. Where in the equity market, you as a customer, by law, are entitled to get the best price in the market. So it makes it extremely competitive and it also protects the consumer.

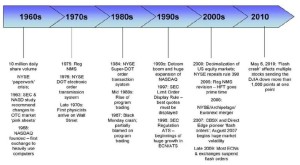

One distinction I would make with what Michael Lewis is saying is that he doesn’t actually distinguish among the many different types of trading strategies, so broadly looking at it, he never actually defines high frequency trading. He kind of casts a really broad net and if you look at that broad net, you’re basically saying high frequency trading is more of a technology or technique. It’s almost like saying e-commerce.

It sounded like it was a very specific label in 1996, but now pretty much every single company, even your brick-and-mortar boutique down the street has an ecommerce profile. Same thing with high frequency trading, where guess what, a lot of people are trading with computers. A lot of people are trading rather frequently.

There’s a whole variety of different strategies and approaches that are in the high-frequency trading world. Lewis kind of blurs the lines and smears them together and as a result he comes out with a message saying high frequency trading is bad.

But at other points in his book he says actually high frequency trading is good, but just a couple different aspects of it. So what I’m referring to here is market making. It’s what I know best. And I don’t think any credible person in the market would ever say that market making is a bad business. Althought, Lewis does make some allusions to market making having some nefarious aspect, but I’m not really sure what his point is there. Mainly, he’s targeting the high-frequency trading industry with his front running allegation.

Michael: What you’re saying is one version of high-frequency trading is market making, trying to make the tiny spread between where you buy it and sell it, and essentially the service is providing liquidity to buyers and sellers, and the business model is to buy slightly lower than you sell.

But I think you’re also saying there’s an entire world of other strategies which involve buying and selling securities quickly, that aren’t providing liquidity in that same way.

Because some of the conspiracy ‑‑ the credible part of the conspiracy theory that Lewis is talking about rests on the idea that hardly any of us who are not in the world of high frequency trading can even grasp what the strategies are. Can you give an example of some strategies without giving up the secret sauce of your own firm, but give us something concrete that we can think about?

Peter: Would you like a market-making strategy or something beyond that?

Michael: Market making I’m going to describe as buy it here, sell it here plus a tiny bit.

Peter: I’m most familiar with market-making strategies but I can kind of speculate on something else. Let’s say you had a strategy where you say whenever I see FedEx is increasing in value by 1% over the course of a day, then I’m going to buy UPS. That’s kind of a pairs type strategy where you’re trading two related companies and you’re saying based on one of these companies moving, another company is going to move.

It’s not necessarily a market-making strategies but it’s one where you’re saying I think that this other component of the market should move because its leading indicator is moving as well.

Michael: The theory being FedEx and UPS are essentially in the same business. What’s good for FedEx is probably good for UPS. And FedEx is moving without UPS responding, so the logical thing is UPS should be moving in that same direction.

Peter: Correct.

Michael: The frequency with which you would need to purchase UPS, we’re doing this on a millisecond basis or a minute basis or over the course of an hour?

Peter: That’s a great question. Let’s say you have this theory that FedEx should always be worth about two times UPS exactly. As soon as you see that it’s worth 2.01 times you’re going to buy UPS because UPS needs to increase in a bit of value to be on par with FedEx. In that example you’ll be watching and every time you see FedEx pick up a little bit more you say now I need to buy UPS. Or if FedEx kicks down you say FedEx is worth 1.99 [times] so now let me sell some UPS and kind of put that back into balance in terms of my portfolio. You wouldn’t wind up doing a lot of trades. But in the end ‑‑ this is a classic strategy that Wall Street has been running since the last century.

Michael: But in the case of algorithmic trading, it’s just sped up, and it could be done in the space of less than a second, in milliseconds?

Peter: Exactly and it’s for much smaller quantities. Instead of someone saying I’m going to wait until they diverge by 5%, and then I’m going to make a big bet on this, which is the way you would have seen it play out on Wall Street, say 30 years ago. Now you have someone saying I’m going to make a lot of smaller bets, when there’s a smaller divergence.

The advantage from a trading perspective is that a lot of these smaller bets you’re less likely to lose a lot of money if your bet goes south. For the market, you could argue that it’s keeping these prices a little bit more closely aligned because you’re doing more frequent adjustments rather than someone doing a large adjustment on a periodic basis.

Profitability

Michael: Which brings up one of the examples I really liked about your book, which is a response to the claim from high-frequency trading critics, the fact that these firms are not unprofitable enough. Or that is to say that on almost every single trading day they’re reporting profit, which in the normal world you go “that’s impossible!” Nobody is that good without there being a trick. Show me the magic trick or the cheating. That’s the allegation.

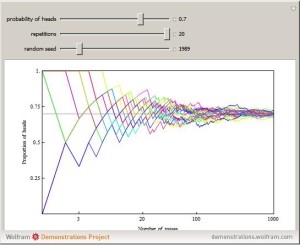

What I really liked about one of your responses to that was here’s why it’s not cheating: We’re doing 1,000 trades, and even if we only have a 51% chance of making some money, when you apply the law of probability over 1,000 different trades, when you make money 51% of the time and lose money 49% of the time, you’re going to end up profitable pretty much every single time. I’m probably butchering your language around that, but maybe you can express that better than me. That was one of the strongest arguments in favor of consistent profitability, was the law of large numbers and probabilities applied to small trades done many times.

Peter: Thank you. You characterized that perfectly. Interestingly enough, just last week, there was a professor from the University of California Santa Cruz who did a research paper that was highlighted in the Wall Street Journal, where he went through one of the firms that Lewis had singled out for this winning record. He went through all their filings and said it’s actually incredible that they lost money on that day, given the law of large numbers.

As you said, the law of large numbers does explain this and it seems counterintuitive at first, but the way I like to explain it to people is if I think about baseball. Over the past 22 years the Yankees have won just 59% of the time. It’s a bit better than even but not much better. If you win slightly more often than you lose and you do it consistently for all of 162 games in the season, you’re likely to come out ahead. They’ve only had one losing season in the past 22 years. That’s kind of remarkable. It’s just 162 times with a tiny bias toward winning, and it comes out to a winning season every time.

The opposite is also true. During the same time the Pittsburgh Pirates won only 45% of the time. They had 20 losing seasons out of the past 22, applied over 162 games.

Now, if you’re trading not 162 times a day but 10,000 times a day, 100,000 times a day, it becomes more and more inevitable that you’re either going to be guaranteed to make money or guaranteed to lose money. The losing money is also another interesting side of the discussion because any firm that is around right now, who is doing this, and is doing it successfully, by definition is making money.

If they had a slight bias to losing money on their trades, they’re already gone. And that’s happened to a number of firms. Some of the people you’ve heard of because they were well known at one point and then they started to lose just slightly more often than they won, and they’re gone. The firms you hear about now of course are going to be the ones with consistent results.

Lastly, there’s another way to think about this, which is that if you are more of a service provider, as opposed to a speculative risk taker, then it also makes sense. If you’re a market maker you’re getting paid for the service of making a market. You’re not speculating on the markets and so the example I gave is if your entrée into the art world is selling greeting cards, you’re selling cards. You’re going to make a penny or two per greeting card. But you’re not going to really lose money. It’s greeting cards, not a high-margin business.

If you are an art investor, you may spend a couple million dollars on a piece of art. It may turn out that that piece of art in ten years is the hottest thing on earth. And now it’s worth 20 or 30-million dollars and you made a huge killing. Or it may turn out that it’s not worth anything at all. It’s a different business model.

When you’re comparing the results of an electronic market maker who’s doing the service repeatedly, 100,000 times a day, million times a day, whatever it may be, versus someone who is making multi-million-dollar bets on obscure derivatives, you’re going to come up with different results.

Michael: Makes sense. I’d like to return to your example of the Yankees. As a Red Sox fan that hurts. I’d like to say A-Rod was a cheater. And don’t mention Big Papi or Manny Ramirez and their PED scandals.

Peter: Definitely no Bucky Dent.

Michael: And please don’t mention Bucky Dent.

Front Running

Michael: On the issue of cheating, Lewis’s main allegation is that a main part of profitability of high-frequency traders is you’re front running and front running is not super easy to define, but I’ll take a stab at it. You can correct me. It’s in the role of market maker a customer comes in to trade and you use the information you gain from their sale or purchase to anticipate that that security is going to respond to that flow. You can either buy ahead of them and sell it to the customer at a higher price or sell ahead of them and purchase from the customer at a lower price. In any case, using the information of the customer flow to make profitable trades. I don’t know if that’s the only definition but that’s my words for front running.

Lewis says this is the main business of high-frequency traders. They’re getting information in a millisecond that’s coming into the exchanges. They’re responding to it quicker than anybody else can. Getting in front of the customer flow, and making guaranteed profits. Tell me why this is wrong.

Peter: First, I think you explain what front running is pretty accurately. Sadly, it did happen in the past and it can still happen today. But in a very different way, and that’s when a broker has a customer’s information on their order. And that particular broker who received the order trades ahead of the customer because they have that information.

What used to happen was the broker would get that information. They would look at the price and quantity on the customer’s order. And then they would go out and trade in the market for their own account, buying or selling ahead of the customer. And then they would turn around and then from their own inventory sell those shares back to the customer at a higher price.

The key things that they relied upon there was the ability to see the price and quantity of the customer’s order, and to be able to give the customer a different price than what the market price was. Those are the key things that they needed.

Lewis doesn’t try to explain how those elements could possibly be present in the current market. And the reason he doesn’t try to explain it is it’s probably because it’s impossible to do so. So you can’t explain how someone is determining the price and quantity of the shares you desire. In today’s market, the orders are anonymous. So if you submit an order to your broker, and that broker then submits it to an exchange, no one in the rest of the market ever knows the quantity of your order or the price of your order.

Even if your order trades against the market maker, that market maker still does not know what the price and quantity on your order were. All they receive is a report that says you transacted this many shares. That’s it. They don’t know what the price of your order was. They don’t know the quantity on your order. That information is never available to them.

As a result, they never have the information that will be a prerequisite to any front-running scam. Beyond that, the issue of manipulating the price to give the customer a different price in the market is also not possible. When Reg NMS came into effect, we have this requirement that the customer must get the best price that is displayed in the markets.

The only way someone can change that price is by buying every single share in the market. So just to be very specific here; if you place an order to buy Microsoft at $49, and Lewis is alleging your front runner is going out there and is going to buy all the shares at $49 ahead of you, and then sell it back to you a penny higher.

They would have to go into the market and on every single exchange buy every single share offered. They may wind up buying 30,000 shares, a million shares, in order to allegedly front run your order of 500 shares. That’s the only way to possibly move the share price. Obviously, that doesn’t make any sense. It’s ridiculous.

Further, if they did move the share price, guess what? There’s already another million shares behind that at the new price point, so they would be the ones selling them back to you. Someone else is already first in line to sell them back to you. It’s impossible for a would-be front-runner to be able to manipulate the price.

It used to be possible when the brokers had more discretion on the pricing. But in today’s market it’s simply not possible. And Lewis never took the time to understand how the market works, what these rules are about price protection in the market, which makes his allegations completely impossible.

I guess the last thing I would say is that he kind of justifies the whole thing by saying you can’t really prove or disprove this because the data doesn’t exist. It couldn’t exist to prove or disprove. And that’s completely false. The data is out there.

We would have a homework assignment for our trainees to look at a particular trade that a strategy did in the market, and explain exactly how the market reacted; what happened after it; what trades occurred after it. All the data is there.

You can get it from a Bloomberg terminal, you can get it from your own systems. This is the industry in the world that is the most awash in data, and it’s completely ridiculous to say that one cannot find any data to substantiate his claims. The only explanation that makes sense for that is that there isn’t any data to substantiate his claims.

Michael: How about this; why do large buy-side firms believe the thesis? That if you’re Putnam or Fidelity and doing large-block trading, do they believe that high-frequency trader are front running them or do they not believe that? Or are they not sure?

Peter: I think there’s no single answer because I think there’s a variety of opinions. That’s something that is very interesting and Lewis kind of glosses over that. For example, Vanguard came out and said all of these changes from electronic markets are good. We’ve seen that our price to complete a trade has decreased by half a percentage point. It’s incredible for them to say this is how much more efficient the markets are nowadays.

The SEC has estimated that for institutional investors, the people you’re talking about, their cost has fallen by about 40% on their trades since 2003. That’s the cost of actually transacting in the market, not the processing after the fact. Literally, the pricing they’re getting in the market versus what they desire has improved by that much. I think on the whole the industry realizes the benefits of the current market structure, and of electronic market makers.

You do have people who are complaining and I think that’s unfortunate, but it’s also understandable. People do have a tendency to blame someone else when things go wrong. It’s very convenient when you take a little risk on your trade, and it goes against you ‑ it’s much more convenient to blame someone else than it is to take responsibility for it. It’s kind of the mantra on Wall Street.

Michael: Yeah, if things go badly it’s the fault of the market. If things go well, it’s because of my brilliance for sure. That’s the only way to get paid.

[1] Actually, the book came out almost a year ago at this point, but I have been slow in uploading this interview! My apologies all around.

Please see related posts:

Book Review of Flash Boys by Michael Lewis

Book Review of Flash Boys Not So Fast, by Peter Kovac

Book Review of Inside The Black Box, by Rishi Narang

and upcoming audio interviews:

with Peter Kovac, Part 2 – Dark Pools, IEX, Disruption, Blowups

and Peter Kovac Part 3 – Cheating and Morality

Post read (885) times.