This post could leave you feeling strange, bewildered, or skeptical, as it does me. I know I’m outside of my comfort zone.

Tim Urban’s posts on AI

A reader sent me a series of Tim Urban papers on the coming Artificial Intelligence revolution. Reading the two-part series (Part I, and Part II) is one of those mind-bending experiences that people otherwise achieve by paying a lot of money, traveling to Bali, and using exotic mild-altering substances.

As the Keanu Reeves character once said in the movie Speed: “Whoa.”

And sure, there’s the economic impact to consider from Artificial Intelligence, which we can somewhat easily imagine. But then there’s the impact beyond that, the part that leaves me feeling shaky.

In myriad industries – data management, financial trading, the military, manufacturing, robotics, and gaming to name a few – artificial intelligence experts are training computers in intelligent functions. The economic impact is massive and promises accelerating gains.

In myriad industries – data management, financial trading, the military, manufacturing, robotics, and gaming to name a few – artificial intelligence experts are training computers in intelligent functions. The economic impact is massive and promises accelerating gains.

Of course we use artificial intelligence already in everyday life in ways unimagined just ten years prior, before the widespread use of iPhone-type devices and apps. My mapping app tells me the best route to drive my kids to school. Siri responds to my voice to tell me who won the World Series in 1918. (If you need Siri to answer that last one, sigh, you know nothing.)

In a paper resulting from a National Bureau of Economic Research conference in September 2017, “Artificial Intelligence and Economic Growth” economists attempt to grapple with the Artificial Intelligence revolution. Is it something that will offer incremental improvements in automation, with the analogy that we move up the automation foodchain, like from the plow to the tractor to the combine-harvester in the 19thand 20thCenturies?

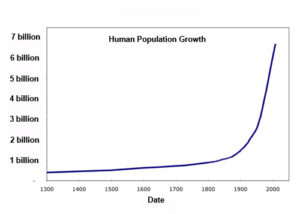

Or does AI instead change the rate at which we innovate, such that economic development occurs at an accelerating pace? Change in this second case happens exponentially – like we see in graphs of population explosions, or the spread of infectious diseases. If AI helps automate physical production – or even more compellingly – automate idea production, then an exponential economic growth explosion due to AI seems increasingly plausible.

The economics paper argues that one big effect will be economic gains to people who control capital versus people who provide labor. That makes intuitive sense since increased automation favors the investor over the worker. From a financial perspective, the innovators who achieve the biggest breakthroughs in AI will likely reap huge rewards. So, plausible long-term effects of AI include accelerating economic growth and accelerating inequality. Which, okay, sounds like a path we’re already on.

The economics paper argues that one big effect will be economic gains to people who control capital versus people who provide labor. That makes intuitive sense since increased automation favors the investor over the worker. From a financial perspective, the innovators who achieve the biggest breakthroughs in AI will likely reap huge rewards. So, plausible long-term effects of AI include accelerating economic growth and accelerating inequality. Which, okay, sounds like a path we’re already on.

But the most intriguing part of Tim Urban’s papers has to do with the question of whether artificial intelligence advances so quickly that we achieve the Singularity? And if so, when? And then what?

The Singularity

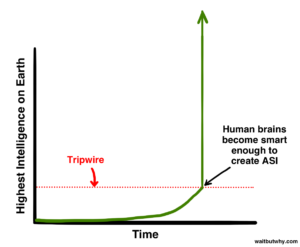

The Singularity, if you’re not a sci-fi or artificial intelligence nerd, refers to that future moment when machine or artificial intelligence gains enough self-learning momentum that it becomes “unbound,” no longer limited to human input or human-level intelligence to advance. It simply surpasses us and keeps on gaining intelligence.

If that happens, we don’t have a good way of understanding the economic (not to mention moral, environmental, or existential) implications. On the positive side, a super-intelligent machine could solve problems that humans simply can’t solve. On the negative side, what guarantee do humans have that a super-intelligent machine wouldn’t disregard our humanity, in the pursuit of solving whatever task it’s working on? The “turn the computer off and turn it back on” hack that the IT department always tells us to do won’t work when the super-intelligent machine knows that trick in advance.

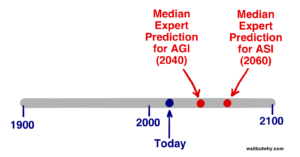

Here’s a bewildering and unsettling thought, as suggested by Tim Urban, who himself builds on the work of other futurists and data scientists. The Singularity may happen in my lifetime.

The “in my lifetime” statement is a crazy-sounding claim, except that it’s backed by a sort of rough consensus belief among computer scientists, economists, and experts on the rapidly observable change in computing power and artificial intelligence technology over recent decades.

Normally I don’t go in for this kind of fuzzy futurism, except for one thing. AI advances are driven by the mathematics of exponential growth. And the mathematics of exponential growth leads us to previously unexpected results. Bear with me here for a moment on an analogy from finance, where I am more comfortable.

Normally I don’t go in for this kind of fuzzy futurism, except for one thing. AI advances are driven by the mathematics of exponential growth. And the mathematics of exponential growth leads us to previously unexpected results. Bear with me here for a moment on an analogy from finance, where I am more comfortable.

Things that Compound Grow

A guiding principle of this blog, my book on personal finance, and everything I try to teach about finance is that the exponential growth of invested money leads to an unexpectedly wealthy future. Since exponential growth occurs in technology, artificial intelligence, and other areas of economic growth as well, I have to be open to the unexpected future there as well.

Machine computation speeds have increased by a factor of 10 raised to the power of 11 (10 with 11 zeros after it) since World War II, comparing the giant vacuum tube machine of 1943 to today’s fastest computer. Most lay people know a popular version of what’s known as Moore’s Law, which observes that computing power doubles every 18 months. Miniaturization, memory storage, and costs all improve in similarly exponential ways. Continuing our compounding improvements in AI, futurists estimate that computers are on pace to match total human intelligence somewhere between 2045 and 2080. From there, rapid advances would likely far surpass human intellectual capacity.

As Tim Urban concludes in his paper, the big issue in artificial intelligence really isn’t economic gains.

Nor is the big issue whether China or some other country is getting ahead of the United States in research into AI. That last issue is kind of like worrying about who will finally capture the Iron throne when Winter is Coming.

No. Rather, if Urban’s summary understanding of our best minds on AI are right – if you give some credence to the Singularity possibly in our lifetime – then the real question Urban asks us to ponder about the Singularity is:

Will It Be A Nice God? 1

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

High Speed trading and D&D alignments

Book Review on Book By Ric Edelman

Book Review: Flash Boys, Not So Fast, by Pete Kovac

Post read (369) times.

- This kicker of a phrase is taken directly from the end of Urban’s Part One, and frankly is just too good not to repeat. ↩