Warning: This is a story about customer service in the banking industry, so reader discretion is advised. Do not read if you are prone to high blood pressure. Also, this is not an apocryphal story. This actually happened to me this week.

Warning: This is a story about customer service in the banking industry, so reader discretion is advised. Do not read if you are prone to high blood pressure. Also, this is not an apocryphal story. This actually happened to me this week.

The Background to the Problem

One of my businesses became inactive last year, so at the end of the year I closed out my checking account for that LLC with Capital One. This Spring I filed articles of dissolution with the Delaware Secretary of State (where the LLC was created), as well as with the Texas Secretary of State (where I was doing business.)

Also this Spring I received a statement from an old $25,000 Capital One Line of Credit affiliated with this business entity. It showed a $0.02 balance owed, a mistaken leftover from the last time I used the line, probably about two years ago. A few months back I tried to close the line in person at the branch but the branch manager said they didn’t handle business lines of credit there, and she gave me a number to call to sort it out with Capital One customer service, over the phone. So far, so good.

Two Pennies

I’m enough of a detail-oriented person when it comes to my businesses that I decided to get in touch with the bank and definitively close out the line of credit.

Two cents is silly, and the result of a bank error from a few years back, but it was a loose thread that I needed to tie off, and anyway it’s probably not a good idea to have open lines of credit that I’ll never use, especially since I had dissolved the business.

Also, I’m a Mary Poppins fan, and a finance-guy, so how can I not appreciate the ironic, iconic importance of two pennies (Tuppence), when it comes to banking stability?

Like I said, I had visited my bank branch to close the account, but the manager told me to call customer service. Evidently Dick Van Dyke was not available at that time.

The Tragedy of Antigone

I called the customer service telephone number at Capital One provided by my branch manager. After receiving an automated voice menu in which “close my line of credit account” was never an option – on the second time through the automated voice menu, I think I pressed ‘1’ for loan account balance – and reached a human.

On her request I gave my first and last name and account number and explained that I needed to close my line of credit.

“Please hold for someone who can help.” Click.

Okay…another two minutes pass.

“Hello, this is Antigone for Capital One, can I have your first and last name and account number?”

Of course she can. Again. Not a problem.

I explain that I would like to close my line of credit associated with one of my business entities which has been inactive for a long time, and that the associated checking account has been closed for months.

This is where the drama begins.

“Uh, do you know you have a balance on the line? We will not be able to close it.”

“I know that. It’s 2 cents. That’s been on there for a couple of years. After I transferred money from my checking account to pay off the balance, the 2 cents showed up. Probably a day’s interest accrual or something like that, by mistake.”

“Ok, but the system won’t let me close the account if you have a balance.”

“But it’s a mistake by the bank,” I replied. “The line always automatically deducted monthly payments from the associated checking account. I made sure to request a full payoff of the line when I closed the checking account.”

“Ok, but the system won’t let you close the account. You’ll have to go into the branch to do it.”

“I have another Capital One business checking account, and I have a Capital One credit card, maybe can you take the 2 cents from there? I’d really like you to have the 2 cents. I understand this is important.” (Because, again, “Tuppence”)

“We can’t do that. You’ll have to go into your local branch.”

“Well, I went to close the account at the branch, but they said they couldn’t close business lines of credit at the bank. It has to be done over the phone, and this was the number the branch manager gave me. Maybe you could just check with someone?”

“Ok, could you please hold and I’ll check?”

“Ok.”

5 minutes of hold music. My soul begins to ache. I can feel the already-advanced process of telomere shortening in my chromosomes accelerate. Antigone returns.

“I’ve checked with my manager, but there’s really nothing that can be done if you’ve got a balance on that line.”

“I understand. But you see, the branch says they can’t close it, and now you say you can’t close it. And I’m afraid if I go back to the branch they’ll say the same thing again. Could you please just recheck, because we’ve got an insolvable problem. I’m really trying to get you your two cents, and I really want to keep your records up to date. But this is beginning to bug me.”

“Ok, let me put you on hold again and call your branch directly to see if I can get them to help you close the account. What’s the address of your branch?”

I look it up online and provide her with the correct address. Then, hold music for another 8 minutes.

Entire civilizations, like the Whos of Whoville on specks of dust under Horton’s protection, grow, flourish, and perish in the interim. Red giants become white dwarfs. And our little blue orb floats alone and unnoticed, two-thirds of the way out on the spiraling Milky Way galaxy.

“Hi, Michael? I reached the branch, but Cynthia who answered the phone said she couldn’t do it, and the branch manager was in a meeting. The best thing is probably to just go down there.”

At this point in the call, 18 minutes into my epic quest to close the Tuppence Line, I’ve moved – in my mind – into full-blown unhappy mode.

The NSA, undoubtedly monitoring this (and every other call we’ve ever made) will have registered a voice-tone recognition alert that the customer on the line, me, is no longer ok with how things are going. Although I am still calm and mostly even-keeled, the absurdity has become too much.

“Antigone, listen, I’m not upset with you, but can you see how this whole episode really doesn’t work, from a customer service perspective? Can you get the absurdity of this? Are you a Mary Poppins fan? I am. Do you remember the Tuppence Song with Dick Van Dyke as the old banker? I understand the importance of 2 cents. Even though it’s a bank error, I really want to pay it, but I can’t. You won’t let me. And even though I’ve now spent 18 minutes trying to help the bank, you won’t let me. And to leave it unresolved like this is really unsettling.”

I urged Antigone to try to elevate the problem with a manager, and to figure out a way to solve the problem for the customer. She promised she would “open an inquiry” with a manager and someone would get back to me. We ended the call.

The Law and the Higher Law

I really don’t blame Antigone. She remained positive and polite throughout the call, albeit ineffective. She isn’t the main problem.

Antigone’s stuck in a bank that values ‘the system’ and ‘efficiency’ – whatever that means and at whatever the cost – over human judgment.

Why do people hate their banks? We hate banks because we sense, rightly, that banks respond to a single set of laws. At every turn, bank customers must be treated a certain way, and therefore be reminded that they are subject to non-negotiable societal laws around process, automation, and efficiency as understood by the company.

Sophocles’ character Antigone, of course, argued that a higher law prevailed over traditional societal law.

In classic Greek theater, the name Antigone has become short-hand for loyalty to a higher moral law – the right to honor our dead – over fealty to a flawed societal rule, punishment for challenging the ruler. I swear I’m not making up Antigone’s name as a customer service rep at Capital One.

I see in my interactions with her and Capital One this week as encapsulating certain fixed rules of customer service in an extremely anomic corporate world. I get it that my bank has a ‘system’ rule about closing lines of credit with outstanding balances.

I don’t expect Capital One’s Antigone to break out of her proscribed role and commit professional suicide, as Sophocles’ Antigone commits bodily suicide, in honor of a higher law.

But for the love of Oedipus’ cursed lineage and Polyneices’ unburied body, can I please get a human being with some power to be reasonable about the higher-order goal of customer service at my bank? For fuck’s sake.

And now I will start an argument with myself.

The Bishop and the Banker – Is Automation a Tragedy?

James Jones, the Bishop of Liverpool, England – a sometime commentator for the BBC such as in this program on prisons – interviewed me last month for an upcoming program the BBC will call “The Bishop and the Banker.”

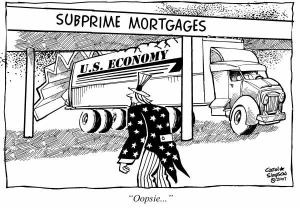

The main thread of his interview query was the following: “By automating the mortgage lending process in the lead-up to the 2008 Crisis (and presumably beyond) did we lose the ‘humanity’ in bank/customer relationships? And his follow-up point by implication: can we reintroduce ‘essential humanity’ to the mortgage lending process?

My answer to the Bishop was essentially “No.” Of course, you don’t just say “no” to a Bishop, so I said more than that, but really that sums it up.

No, I don’t think automation is the key culprit of the 2008 Crisis, and therefore ‘reintroducing humanity,’ to the lending relationship is not the key solution.

During the interview I talked about the price of tomatoes, as an analogy for mortgages. Yes, sometimes modern tomatoes are tasteless cardboard things, but they also come cheaply and affordably. Few people would choose to pay $9 for tomatoes, which is the price we could probably retail them in bulk if we returned to the labor-intensive ‘humane’ way of growing tomatoes – in our back yards.

Adam Smith’s point about the division of labor in pin-making still prevails. Incredible gains come from splitting up the task of producing the pin-head from the pin-body. Efficiency in human production generally is a good thing, with great customer benefits. Few people, if they understood all the consequences, want to take out super-expensive mortgages, even if George Bailey of Bailey Building and Loan Association kindly oversees the whole process himself.

What I think the Bishop missed, so I’ll reiterate my initial response to him here, is that the efficiencies of mortgage lending since the early 1980s are totally awesome. Why? Because my 2.75% interest rate 15-year mortgage is totally awesome. And that kind of rate is not at all possible from the ‘humanizing’ Bailey Building and Loan Association. Without all the efficiencies of this dehumanizing specialization, mortgages right now would probably cost 8-10%.

This interview came back to my mind this week, however, as I smacked up against the ultimate dehumanizing experience at Capital One Bank. Am I a hypocrite for believing strongly in the efficiencies of mortgage lending when it benefits me, but railing against dehumanized customer service when I’m on the receiving end?

I would still answer the Bishop the same way, but my heightened blood pressure from Capital One gave me a new chance to reconsider his question.

I still don’t think we should blame 2008 on the dehumanization of mortgage underwriting, although I need to be careful to figure out why efficiency works in one context and not the other, aside from how it affects me personally.

How to reconcile this, aka how not to be a self-serving hypocrite

Can a bank be both efficient (cheap mortgage money is good) and humane (torture me for Tuppence is bad)?

One solution it seems to me is that Antigone, and all of her customer service cohort, needs more power to use human judgment. She should never have to spend 18 minutes with me on the phone – in addition to whatever follow-up time she spent afterwards – trying to solve a problem worth two cents to the bank. She needed to be trusted with business judgment, which clearly nobody in her chain of command has thought to give her. To be thwarted twice in her quest to over-ride the ‘system’ means the earthly law of systemic efficiency needs to be trumped by the higher-power law of human judgment.

I think we hate banks because for the most part we sense that there’s no over-ride of the system available for person-to-person judgment. I’m enough of an Adam Smithian to want total bank efficiency, but I also want to avoid the absurdities of bureaucratization.

The NSA treatment

In my imaginary non-existent poll of bank customers this week – 98% of people reported disappointment with their bank’s customer service. Why is that?

At base we suspect, rightly, that the bank couldn’t care less about us as individuals. Furthermore, banks operate within such a highly regulated environment that their entire frame of reference is to fit customers into neatly defined market and regulatory segments.

We don’t think of ourselves as bits of data, but the bank does, and we can’t change that.

Which reminds me:

Among the most frightening aspects of the recent NSA phone-tracking revelations is the creeping fear that we could, any one of us, be caught up helplessly in a faceless bureaucratic nightmare.

Personally, I prefer my spies to use common sense, actual evidence, the justice system, and human judgment before choosing who to target for snooping on the phone and internet. Apparently, however, all citizens’ private behavior can be subject to the same anonymous tracking, classification, treatment. This doesn’t sound like a good direction for us all to go in.

Advanced efficient technology, whether for snooping or banking, has temporarily outstripped our societal ability to set up limits to the system.

The 2008 mortgage crisis also felt like it came from this same uncomfortable place of valuing the anonymous efficiency of the system. At least a part of the Occupy Wall Street movement responded to this terrible feeling that we are just data-points, adrift in a cruel economy.

If hyper-toxic CDOs rip financial holes in our biggest banks, and 6 million people suddenly get laid off in a 2 year period, who can you appeal to? Two million homes get foreclosed upon by robo-signing attorneys. $80 Billion of public funds get pledged from one day to the next – to prop up systemically essential banks still paying bonuses to their employees. The efficiency of the “system” must be preserved at all costs, but what about the basic humanity? What about what’s ‘right’?

I don’t yet think the cruel automation of Skynet – whether in banking or the NSA – has permanently won this war. But we’ve got to figure out a few higher laws that trump the lower-order laws of the system. We need a new Sophocles to remind us of what’s right.

Postscript to my Tuppence Debacle with Capital One

After I’d written most of this post, a representative from Capital One Bank called me today to tell me, in a treacly voice reminiscent of Bill Lumbergh in Office Space, that he’d resolved the problem for me. “We’re just going to go ahead and forget about that two cents, hmmMK? It seems it was from two years ago, so even though technically it’s still owed we’re just going to go ahead and take care of it on our end, hmmMK? Is there anything else I can help you with?”

Um. No. You’ve been a big help already. I refrained from telling him a less Julie Andrews version of the phrase “Go Fly A Kite.”

If you’ve got tuppence for paper and string, you can have your own set of wings, with your feet on the ground, you’re a bird in flight with your fist holding tight (da dum dum) to the strong of a kite. Ooooh, let’s go fly a kite.

Post read (21819) times.

In my imagination, traditional banking used to be the best business. You’d get to close up shop at 3pm on a Friday. This, despite the fact that bank customers get paychecks on Fridays. Sorry folks, we’re closed because we have to have our people inside the vault, counting all that sweet, sweet, money.

In my imagination, traditional banking used to be the best business. You’d get to close up shop at 3pm on a Friday. This, despite the fact that bank customers get paychecks on Fridays. Sorry folks, we’re closed because we have to have our people inside the vault, counting all that sweet, sweet, money. But man-oh-man if somebody can figure out how to do that function – maybe through a combination of nanotechnology, blockchain software, and laser-beams – I am gone, baby, gone from my bank.

But man-oh-man if somebody can figure out how to do that function – maybe through a combination of nanotechnology, blockchain software, and laser-beams – I am gone, baby, gone from my bank.