I’m visiting my parents on Cape Cod this month. My father recently turned 90, and my mother decided to open the long-buried safe where my father kept his coin collection. This offered a brief moment of Geraldo Rivera-type drama. What treasures, buried for decades, would we discover? Tune in after the commercial break…

Ok! We’re back! And…

The haul fills less than half a shoe box. Mom got a quote from their local coin and stamp shop. This long-buried treasure is worth $728. At least, that’s what the dealer would pay for it. Smaug’s glittering horde this is not.

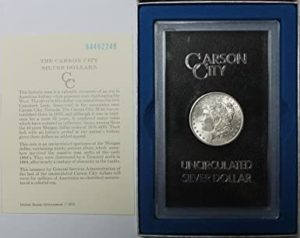

For nerdy numismatists among you, I’ll briefly describe the coins: a ¼ ounce gold coin; an 1877 U.S. Trade Dollar; two Carson City Morgan Silver Dollars (uncirculated, 1883 and 1884), five Peace Dollars, circulated from 1891 to 1934; three Spanish Carolus III Reales, ranging from 1784 to 1806; and two French Indo-China coins, issued a little more than 100 years ago.

I spent some time trying to figure out how much this little collection would cost to accumulate today. I checked Ebay.com, but also specialist sites like Coinquest.com, Greysheet.com and ApMex.com. And then some books I’m about to mention.

The collection would cost between $1,300 and $1,600 to put together.

In other words, the quote from the dealer is about half what it would cost to acquire the collection.

I bought two books at the dealer’s shop, a blue-covered “Handbook of United States Coins 2021: The Official Blue Book 78th Edition” and a red-covered “A Guide Book of United States Coins 2021: The Official Red Book 74th Edition.”

Both books have the same author and the same publisher. Both provide a comprehensive catalogue — lists upon lists upon lists — of coins and prices. They are basically the same book, with one crucial difference. One is for collectors (retail) while the other is for dealers (wholesale).

The issue comes down to what the finance world knows as the “Bid-Ask Spread.” In other words, the difference between how much retail purchasers pay to acquire the asset — the “ask”— and how much dealers will pay to take it off your hands — the “bid.”

Comparing the blue and red books side by side is fun. It would cost you about $39 to acquire my father’s 1927 silver Peace Dollar (the ask.) But the dealer will pay just $21 for the same coin (the bid.) It would cost you about $210 to acquire my father’s 1884 Morgan dollar (the ask.) But the dealer would pay just $150 for the same coin.

Sometime in the 1980s, probably at the same time gold prices were rising rapidly, my father became interested in coins. A mania for precious metals and coins has long cursed unsophisticated financial minds, like my father’s, but interest spikes particularly in moments of increased fear — such as the recession in the early 1980s. And also after gold and silver increase rapidly in price. In other words, moments like this one. Which makes his lapses of financial judgment in the 1980s relevant for us in the 2020s.

The problem with coins as investments is not that they are inherently fraudulent, per se. The idea that a dealer will charge an extraordinarily large bid-ask spread is not the same as fraud. Bid-ask spreads, in many cases, are fine. The issue is a question of degree, as well as a question of unequal information. Smaller spreads are obviously better for the purchaser/investor/collector, while bigger spreads can be better for the dealer. Assets with a huge bid-ask spread, like collectible coins, become inappropriate in part because of their inefficiency in trades.

Unequal information about the bid-ask spread gets to the heart of where mere inefficiency slides gently, maybe imperceptibly, into fraud. If the purchaser/investor/collector does not know that a huge big-ask spread exists and likely will persist in the future, rendering the asset extremely inefficient, then we should worry about fraud.That was one of the issues in the multi-state enforcement action against precious metal marketing company Metals.com earlier this year. They targeted the credulous and frightened, mostly elderly conservatives who watch and read right-wing media, and mercilessly charged markups so large that they constituted fraud.

My father’s own coin collection, as it exists in 2020, I mostly consider harmless. I mean, it wasn’t a good investment. But there’s an aesthetic and maybe intellectual pleasure to collecting old things, and that’s fine. My view is that because of their historical and aesthetic significance, his coins are preferable to accumulating a thousand dollars’ worth of Beanie Babies. Although it is, admittedly, more difficult to hug coins than Beanie Babies.

Coins don’t work well as investments. But they are OK as collectibles, I guess, because people like what they like.

The details had been a bit lost in family history, but my mother told me that, in fact, my father and his business partner had been defrauded on coin investments in the 1980s. My father’s memory is not good anymore, so I called up his old partner, now 80, to find out more.

A well-trusted accountant had introduced them to a pension advisory group, which helped them invest some of the firm’s pension in rare coins, approximately $50,000 worth, according to my father’s partner. Around the time they figured out that a motel investment (also totally inappropriate for my father and his partner’s level of sophistication) had gone sideways, they were contacted by the state attorney general investigating their pension advisor.

Unsurprisingly, in the end, they had paid huge markups on their coins. My father’s partner estimated they took a 30 percent loss on that portion of the pension, in the course of cutting ties with the advisor. That actually sounds to me about what one would expect, even with no outright fraud. That’s pretty much just the bid-ask spread. The motel was a larger percentage loss on a bigger investment. In the end, employee pensions were made whole on the losses, but my father and his partner took losses in their own pensions — as the business owners who should have known better.

Seems about right.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Please see related posts:

Metals.com – The Long Con and The Short Con

Texas Bullion Depository – What Exactly Is The Point?

Post read (188) times.