The United States does not currently issue bonds with maturities longer than 30 years, but the idea of super long-dated national debt is back in the air. Long-dated, as in bonds due in 100 years. One reason 100-year bonds are kind of neat is that nobody alive right now ever needs to worry about paying the principal back!

The United States does not currently issue bonds with maturities longer than 30 years, but the idea of super long-dated national debt is back in the air. Long-dated, as in bonds due in 100 years. One reason 100-year bonds are kind of neat is that nobody alive right now ever needs to worry about paying the principal back!

Setting snark to the side (for just a moment), Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, in an interview in December, appeared open to the idea of 50-year or 100-year bonds, floated by financial newspaper Barron’s back in November 2016.

Barron’s followed up in February with the report that Mnuchin asked his staff at the Treasury department to look into the pros and cons of 100-year debt.

Some of the best reasons for the United States to issue 100-year bonds fit reasonable, prudential, debt-management principles. Other reasons facilitate wackier scenarios. I’ll describe both.

Some of the best reasons for the United States to issue 100-year bonds fit reasonable, prudential, debt-management principles. Other reasons facilitate wackier scenarios. I’ll describe both.

But first, who would buy 100-year bonds from the United States? Buyers are not typically individuals like you and me, but rather institutions that have to make payouts far in the future.

Barbara Mckenna, Managing Principal of Longfellow Investment Management Co, a Boston-based firm managing over $9 billion in assets, noted to me last week that buyers of ultra long-dated bonds tend to be pension funds and life insurance companies, institutions which need assets to match their liabilities, stretching into the future for many decades.

These were the buyers for Austria’s 70-year debt issued in late 2016 at a rate of 1.53 percent. Ireland and Belgium both issued 100-year bonds earlier in 2016 presumably to that type of buyer as well, both reportedly with a 2.3 percent coupon.

“Feed the ducks while they’re quacking,” we’d often say in my old bond salesman days, when we issued new debt. There’s an element of that to justify the US issuing 100-year bonds. Right now, the pension funds and insurance company ducks would happily quack for extremely long-dated US Treasuries, so we might as well satisfy their hunger.

The three most legitimate reasons for the US to issue ultra long-term debt are:

- To ease “rollover” risk,

- To fund ourselves at historically low rates, saving money, and

- To facilitate long-dated corporate bond issuance

First, if your country issues mostly short-term debt, as ours does, the “rollover” problem happens constantly. If you have, on average, more long-term debt including for example 100-year bonds, you’ve gone some way toward relieving your rollover problem.

Next, the cost-savings from long-term low rates could be significant. A few numbers can help put this into context.

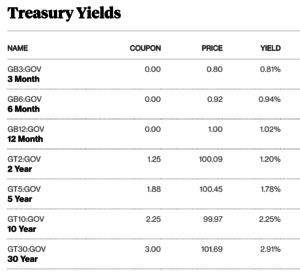

The federal government currently owes approximately $19 trillion to all creditors, and paid $433 billion in interest on its debt last year.

The federal government pays 2.26 percent on all of its debts, as of March 31, 2017, an extraordinary low rate.

15 year ago, the average interest rate on long-dated bonds was 8.27 percent.

10 years ago, the average interest rate on long-dated bonds was 7.55 percent.

Right now a 100-year bond – depending on a variety of factors such as the size of issuance and the demand from investors – could cost something like the current rate on 30-year bonds, or approximately 3 percent per year. McKenna agreed with me that a 100-year bond “probably would not be dramatically different from a 30year bond in terms of yield.” It might cost the US government a bit more, although it also might cost less.

While a 3 percent 100-year bond would represent a higher rate than the US currently pays on average over all, locking in that rate for a long-time probably offers big interest cost savings over the long run.

While a 3 percent 100-year bond would represent a higher rate than the US currently pays on average over all, locking in that rate for a long-time probably offers big interest cost savings over the long run.

We’ve got close to $2 trillion in long-dated bonds outstanding currently, due between 10 and 30 years from now. To point out some simple math (albeit simple math with a lot of zeros involved) a 1 percent drop in the average interest rate on a trillion dollars in long-dated bonds saves $10 billion per year in interest payments.

The third reason for 100 year bonds – and this reason appeals more to bond nerds like me, concerned with smooth-functioning capital markets – is that private corporations can issue more long-dated debt if there are long-dated US Treasury bonds to compare them to. Bond traders really like corporate bonds to match the length of government bonds, as it makes hedging and trading those corporate bonds much easier.

So 100-year US Treasury bonds aren’t crazy, could be issued affordably, and offer some capital market advantages.

Now, you’ve been patient with me and my bond math, so let’s get a little crazy. For readers interested in historical bond trivia – and yes, I’m talking to both of you – ultra long-dated bonds have interesting ties to global catastrophes.

England issued perpetual bonds to finance itself during the Napoleonic Wars, and 100-year debt to finance itself during World War One.

I think of this global catastrophe and 100-year bonds because a time may indeed come in the medium-term future when we have trouble rolling over our debts.

If we were in a shooting war with China – or even just a nasty trade war – for example, we might have trouble with the fact that Chinese institutions own approximately $1 trillion of US sovereign debt. Heck, if we get into a shooting war with North Korea this week or next week we might face rollover trouble, as a signal from Chinese institutions displeased with our unilateral military actions.

If we were in a shooting war with China – or even just a nasty trade war – for example, we might have trouble with the fact that Chinese institutions own approximately $1 trillion of US sovereign debt. Heck, if we get into a shooting war with North Korea this week or next week we might face rollover trouble, as a signal from Chinese institutions displeased with our unilateral military actions.

Fortunately, our current President has deep experience with the inability to roll over debts. He ran his casinos into the ground this way. Given his experience, he stated his plans for federal debt issuance while still a candidate, just last summer.

“I’ve borrowed knowing that you can pay back with discounts. I would borrow knowing that if the economy crashed, you could make a deal.”

Oh, sweet mercy, please, no. But then a few days later candidate Trump clarified, default isn’t really necessary. “People said I want to go and buy debt and default on debt. I mean, these people are crazy. This is the United States government.”

I was starting to feel better.

But then he continued,

“First of all, you never have to default because you print the money, I hate to tell you, okay, so there’s never a default.”

Ah, yes. Thank you Mr. President for clarifying your views on sovereign debt.

Dear Treasury Secretary Mnuchin: Can we please issue massive amounts of 100-year bonds quickly before anyone re-reads these quotes and thinks about them too closely?

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and the Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

Trump and the coming Financial Crisis

Book Review: The Making of Donald Trump by David Cay Johnston

Post read (625) times.