Q. We have a number of investments through Vanguard – small, mid and large cap, some real estate and bonds. All have low costs. Our advisor (from another provider) recently suggested we rebalance, moving some small and mid-cap to large-cap funds. She said we should do this via “loss harvesting.” I have tried to read up and look at the funds online to figure what funds would be smart to sell. But the information provided is confusing (and seems to change) and it seems somewhat complicated. Any advice on how best to proceed such as what metrics to base the decision on?

B. Dempsey, San Antonio TX

A. The goal of tax loss harvesting is, through a careful series of sales, to offset some gains you might have from selling an asset with losses you might incur in the same calendar year. Losses that offset gains can leave you with a smaller tax bill. This is especially relevant if you have highly appreciated assets, or assets that were gifted to you that were bought at a much lower price. (Having a “low basis” in investment lingo.)

That’s the theory.

Tax loss harvesting is easiest to understand on individual stocks. Let’s say your Google stock appreciated by $50K based on where you sold it and you owed $7,500 on the gains because of the 15% long term capital gains tax rate. And then let’s say you also sold Pepsi in the same year, and you lost $10 thousand between where you bought it and where you sold it. The $10 thousand loss on Pepsi can be netted against the $50 thousand gain on Google if the sales occur in the same year. The result: you are only taxed 15 percent on $40 thousand in capital gains, and your tax bill drops by $1,500. Which is cool.

But frankly it isn’t probably as important a factor for your long term net worth than the decision in the first place to own, or not own, Google or Pepsi. And in what proportions, and for how long.

As always when people decide to get clever about saving on taxes, my very strong instinct is to remind them that taxes are the tail, stocks are the dog. Do not let your clever tax strategy (the tail) determine your investment asset allocation (the dog).

You can do this same netting of gains and losses on short-term stock holdings as well, which usually incur a higher tax rate since short term capital gains taxes match your income tax rate. Probably something above 15 percent.

If this seems confusing so far, I think that’s a good sign you don’t want to do it on your own and you may either need to hire an advisor or deputize your existing advisor to do it for you.

I’m usually somewhere between skeptical and opposed to introducing investment complexity and additional advisors to one’s investment life, so I’ll try to offer a bit more about the narrow set of situations you might consider this for, as well as ways to accomplish this over time.

Tax loss harvesting is something you’d only do in your taxable (non-retirement) accounts, since it’s supposed to address the potential problem of capital gains. You won’t ever pay any capital gains in your tax-deferred retirement accounts.

I think it’s also worth saying up front that the most tax-efficient strategy you can do with your taxable investment portfolio in every case is: never, ever sell.

Under current law, assets you never sell produce no capital gains taxes at the time of your death for you or your heirs. While your advisor is suggesting you “do something” (rebalancing) and then “do another something” (tax loss harvesting) as a result, my instinct is usually to tell people to “do nothing,” especially if you want to be tax-efficient.

If you do go ahead and reposition your portfolio anyway, it becomes relevant at the end of the year in which you might pay capital gains to think about whether other sales you can do might produce tax-offsetting losses.

In 2023, it would not have been surprising if you had losses in your bond portfolio, for example. Individual securities that went down from the time you bought them would be other candidates for locking in losses, although I again would not advise selling something just “for the taxes.”

As for tax loss harvesting by selling a small-cap or medium-cap mutual fund, that seems too difficult for an individual to undertake on their own. You probably need to engage with an advisor if you want to do that, and that’s going to cost you money, which will raise the issue of whether a tax loss harvesting strategy is overall worth it. (more on that below)

Another skeptical note, from me: Does incurring taxes by selling your existing low-cost mid-cap and small-cap index funds, and then doing tax-loss harvesting after the sales, truly improve your portfolio? In most market environments indexes of different capitalization are very highly correlated, so you are getting questionable improvements while upping your tax bill and maybe upping your management fees?

There are at least two other ways to rebalance in a more tax efficient way. One would be to direct new purchases from the bond interest payments and stock dividends into larger cap funds. It would take a longer period of time but without any capital gains taxes. Another would be to just decide any new purchases go into large caps, but without selling the existing positions. A third way is to make the reallocation through changes to your non-taxable portfolio (like within a retirement account), as that doesn’t create a tax bill. Obviously I don’t know the positions of your portfolio and I don’t know your specific financial situation. I’m just a skeptical guy asking whether this advisor is really helping, or is this advisor making suggestions that just look like they are helping?

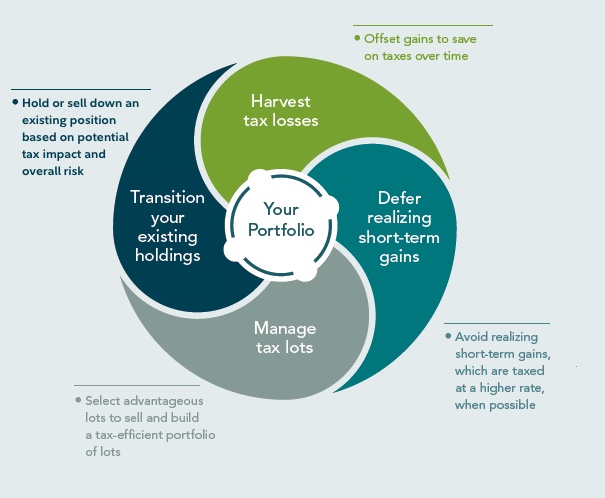

Going slightly beyond your question, there also exists the relatively new idea in investment management of actively tax-loss harvesting your existing taxable portfolio, not for rebalancing but specifically for tax efficiency.

Brokerages offer tax-loss harvesting strategy as a service within a portfolio that can act like a mutual fund. Fidelity for example offers something that should offer the performance of the S&P500 index, but at any given time they buy and sell individual stocks in ways that minimize capital gains taxes through tax loss harvesting. Since they charge 0.2 to 0.4 percent for this service, they would need to deliver some after-tax outperformance.

An academic research study from 2020 suggests that a tax loss harvesting program like this could save between 0.8 and 1.08 percent per year on your portfolio.

Since tax loss harvesting adds complexity to your investment life, I think it only becomes relevant if you have a large – probably multi-million dollar – taxable portfolio.

At that scale, paying an advisor to generate an additional estimated 0.6 per year on your taxable portfolio may make sense.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (27) times.