The 116th Congress convened this [ast week, and Paul Ryan has left the building.

The 116th Congress convened this [ast week, and Paul Ryan has left the building.

Hey bro: don’t let the Capitol Building doors hit you on the way out. Wow, what a disappointment. History will not treat him well.

Words vs. Actions

Ryan entered Congress as a conservative fiscal policy wonk from Wisconsin 20 years ago, rose to prominence as a budget hawk, and became Speaker of the House in 2015 on the basis of that reputation. As speaker, he threw that reputation all away.

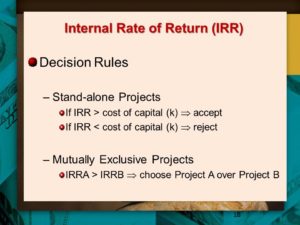

I too am a fiscal conservative. By that I mean government should not agree to do things for which we do not have a reasonable payment plan. Yes, some government debt is sustainable in the long run, but all tax and spending policies need to meet a basic fiscal test: Can we afford it in the decades to come? We do not promise rainbow cupcakes on every plate and unicorns in every backyard unless we can afford it.

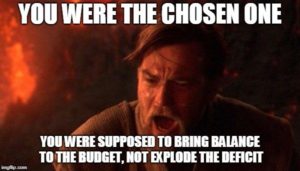

For fiscal conservatives, Paul Ryan was the Chosen One.

To compare Ryan’s reputation as he accumulated power to his accomplishments once he had power – the grand canyon between his stated goals and what he did as Speaker – is to expose him as either a colossal failure or an outright fraud. Those are really the only two options.

In 2012, Ryan told Fox News’ Sean Hannity about government debt under the Obama administration: “This is the most predictable economic crisis we have ever had in this country, it’s a debt crisis. Our debt literally gets out of control and it ends the American dream as we know it.” Fortunately, according to Ryan, we had him to save us.

He went on: “Let’s get back to a path of prosperity and debt reduction and paying the debt off. So what I’m basically saying is we are offering the country a choice of two futures…The more you kick the can, the worst [sic] it gets the more imperiled our economy becomes and the more of a debt crisis we have on our hands.”

He went on: “Let’s get back to a path of prosperity and debt reduction and paying the debt off. So what I’m basically saying is we are offering the country a choice of two futures…The more you kick the can, the worst [sic] it gets the more imperiled our economy becomes and the more of a debt crisis we have on our hands.”

Anyway, the joke’s on us, apparently Ryan was only kidding about the debt problem in the years leading up to his Speakership.

Ryan, as House Speaker in the era from 2016 to 2018, finally had the chance to back up his ideas with legislation.

Yes, power is shared among many people in Washington. Enacting one’s vision is hard. But Ryan completely drove the bus for three years with the House, Senate and White House unified under the same party. As a supposed budget hawk, however, he accelerated that bus 90 miles an hour into harm’s way.

Debt and Deficits

On October 29 2015, when he became Speaker, until the end of 2018, the total public debt outstanding rose from $18.1 trillion to $21.8 trillion. In other words, national debt rose by more than a trillion dollars per year under Ryan’s leadership.

On October 29 2015, when he became Speaker, until the end of 2018, the total public debt outstanding rose from $18.1 trillion to $21.8 trillion. In other words, national debt rose by more than a trillion dollars per year under Ryan’s leadership.

But that’s really not the most important place to view the huge gulf between his stated goals and accomplishments.

Annual budget deficits are an even better measure, since Congress sets budgets annually. The budget deficit in 2015 was $439 billion, but rose to $782 billion in 2018. That rise in the budget deficit is Paul Ryan’s direct legacy. That’s the so-called budget hawk’s accomplishment. In the 5 years before Ryan became speaker, by contrast, annual deficits fell each year. That’s also his legacy. He reversed a good trend and made it terrible.

Into the ditch

But even these terrible numbers have to be taken in further context to show how bad he was. During recessions we allow for government debt to expand, as a cushion on the private sector’s woes. During boom times we look to pare back debt. The massive deficits and ballooning federal debt under Ryan tenure are particularly egregious because it happened under boom times, with historic low unemployment, fast growth, low inflation, and rising asset prices. Even under ideal conditions, Ryan recklessly drove our fiscal bus into the ditch.

But the worst of all was the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, in which Ryan locked in higher budget deficits for years to come, with a deficit increases estimated between $1 and $1.5 trillion.

Paul Ryan’s failure and fraud is of a particularly enraging type. By all accounts and unlike many of his colleagues in Congress, Ryan does know how budgets work. But in order to pass the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act he engaged in a series of budgeting tricks: Tax cuts that end abruptly after a certain number of years to “make the math work.”

Blame Trump? No.

And why am I not blaming Trump, for example, under whose leadership over the past two years these debt and deficit numbers also increased? Three reasons. First, Trump never claimed to be a budgets guy. Second, Congress, not the President, controls tax and spending policy. Third, Trump is doing largely what he said he’d do.

And why am I not blaming Trump, for example, under whose leadership over the past two years these debt and deficit numbers also increased? Three reasons. First, Trump never claimed to be a budgets guy. Second, Congress, not the President, controls tax and spending policy. Third, Trump is doing largely what he said he’d do.

Trump throughout his campaign advocated protectionist industrial trade policies for the steel and auto industries, trade wars, tariffs, picking winners and losers through economic development deals, and not worrying about over-indebtedness because you can always either renege on your debts or just inflate away the problem. Each of Trump’s ideas is uniquely terrible, and taken together are potentially catastrophic. But at least the multiply bankrupt casino-owner has stayed consistent to his promises. He’s doing what he said he’d do. In his own inimitable way Trump is straightforward on economic policy.

But Paul Ryan – this guy has some nerve. He spent his career railing against the government’s fiscal irresponsibility. He became Speaker of the House of a supposedly irresponsible tax-cuts-and-spending Congress and said “hold my beer.” Drunken sailors on shore leave for just 24 hours have shown more fiscal restraint than Paul Ryan with the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act.

It’s almost as if Ryan didn’t really mean any of the things he’d spent 20 years talking about. I’m shaving his head and ringing the shame bell loudly as Paul Ryan walks away from the capital.

It’s almost as if Ryan didn’t really mean any of the things he’d spent 20 years talking about. I’m shaving his head and ringing the shame bell loudly as Paul Ryan walks away from the capital.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

The Principled Republican Opposition to Trump?

Where Are The Fiscal Conservatives On War Costs?

Post read (649) times.