Despite all reports to the contrary, I have not suspended my campaign for National Personal Financial Benevolent Dictator (NPFBD).

In fact, today I add a new plank to my platform.

My latest plank is regulation through comprehension, rather than through disclosure. I’ll unpack what I mean by that below.

I’m in the process of renewing the Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) on my house.

As you can imagine, my mailbox and email box filled to the brim with dozens upon dozens of disclosure document pages for my signature. These are virtually unreadable and they will go unread by me. Nevertheless, I will sign them.

Lauren Willis, a law professor whose criticism of financial literacy programs I recently described admiringly, has a replacement for these disclosure documents, and I’ve stolen her idea for my platform.

She argues in a 2017 paper “The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Quest for Consumer Comprehension” that financial products regulation should focus less on disclosure and more on creating a system of consumer comprehension.

Here’s what she means. Financial service providers – of credit cards, insurance, investments, and mortgages – would need to regularly show to regulators that a large majority of their customers could pass a simple comprehension test about their product.

Placing the burden on financial firms to stay consumer compliant is analogous to requiring car companies to prove they can meet emissions standards, or toy manufacturers can meet child safety standards.

As long as, say, 80% of credit cards users could ace a quiz about what their interest rate is and the cost of their late fees, and maybe also what the mandatory arbitration clause means, the credit card company would be in the clear. Or, as long as 70% of insurance buyers could accurately describe the meaning of their deductible, premium, their coverage and exceptions, they are good. Provided that 85% of mortgage borrowers correctly describe in a quiz their terms and what their payments will look like if the adjustable rate changes in 3 years, the product is fine.

I’m making up these numbers and these requirements just to provide some sense of what a consumer-comprehension quiz would look like. The point from Willis is two-fold: Disclosing terms in tiny print over 30 pages never helps. It leaves the burden on the consumer. Instead, the burden should be on the firm to show – with a consumer comprehension audit – that customers know what they are buying. After all, isn’t that the original point of these non-effective disclosures in the first place?

Our default system is free market. And I’m a free markets guy. I like classical economics’ trust that prices and quantities will reach equilibrium as long as we minimize frictions like taxes and government interference. Few people will purchase a $10 tomato when a $1 is available, says classical economics. Firms able to offer $1 tomatoes will sell many more units than a purveyor of Gucci tomatoes. I understand this concept very well.

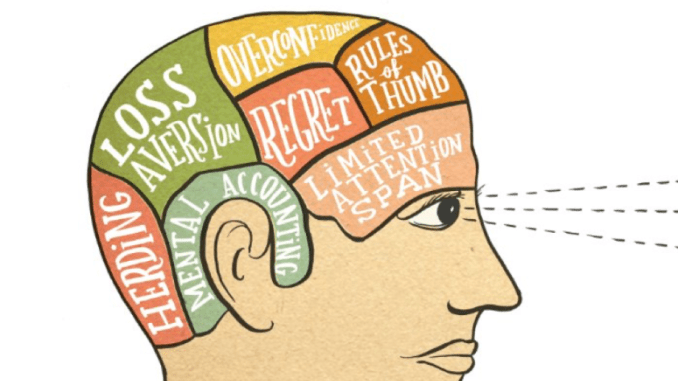

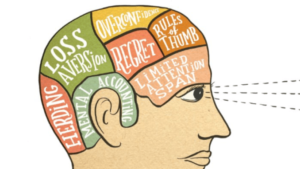

But the last forty years of behavioral finance has taught us that classical equilibrium theory doesn’t work as well in areas like personal finance, because of predictable inherent biases and errors of thought. As a result, people are unknowingly purchasing $10 tomatoes when they should, logically, be buying $1 tomatoes. The inefficiency endures because of human error in predictable, repeatable, ways. And if we know these errors in advance we should build in protections.

And yes, regulation like this could be expensive to firms.

But the alternative is not free market efficiency. The alternative is people paying for $10 tomatoes out of predictable ignorance.

As NPFBD, I am used to people not understanding the brilliance of my proposals at first glance. But I am both benevolent and a dictator, so I will further explain and address your concerns.

One objection: Some people just can’t be taught, because math is hard. And financial concepts are especially hard. Ok, true. But Willis’ proposal focuses on setting a target for average comprehension. Like maybe just seventy percent of customers have to pass the “comprehension audit.” Not everyone. Just a good majority. That seems reasonable and flexible to me.

Another objection: Comprehension seems costly for firms, as they would be required to create educational programs around their products. Maybe. But wouldn’t it also seem that firms facing the potentially high cost of consumer education would be greatly incentivized to simplify these same financial products? Wouldn’t firms pivot towards selling things that any fifth grader could understand?

I am certain, for example, that variable annuities would rightly disappear from the face of the earth if insurance companies were forced to educate consumers about how they actually work. Because, quite simply, they cannot be explained in simple terms.

You know what else is costly? 25% of sub-prime mortgage borrowers defaulting in the same year, sending the world financial system into a tailspin, and requiring an unlimited bailout of all of Wall Street.

Another objection: True financial complexity cannot be captured in short consumer-education segments. Willis addresses this by analogy with energy-efficiency regulation. Simple labelling with stars currently informs us consumers of energy-efficient dishwashers and refrigerators. I don’t have to be an electrical engineer to understand the energy-efficiency star system. I just need to know enough about how the labelling of stars on my dishwasher works. A simple and consistent labelling system for credit cards, mortgage, and investment products could go a very long way to building consumer comprehension.

This is a results-oriented approach to regulation. It’s not about the number of pages of fine print. It’s about proving – with reasonable room for variation – that people using the products actually know what they’re getting and at what price.

I’m knowledgeable enough about behavioral finance to know that the unfettered free market will lead to worse results for many. But I’m cynical enough to recognize that traditional financial product regulation – in the form of more disclosures – creates an ever-increasing paperwork and liability burden on businesses, but without addressing the core problem.

I don’t read disclosures even on my own HELOC application. In fact, nobody does. This creates a “You pretend to disclose, while I’ll pretend to be protected” universal cynicism toward the regulation of personal financial products.

As your NPFBD, I’ll focus less on disclosure and more on consumer comprehension instead.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post

My Campaign For NPFBD – Focus on retirement investing

Renewing my HELOC in 2015 – Judgement vs. Objectivity

Post read (132) times.