Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Editors Note: I highly recommend consuming this interview in audio form, by clicking the start box above. So much more interesting!

Please see interview Part one with Peter Kovac here, on HFT market making front-running and profitability

Part 2 of the interview HERE:

Michael: Hi, my name is Michael, and I used to be a hedge fund manager.

Michael: Flash Boys: Not So Fast came out recently[1] on Amazon and is available. One version I will paraphrase parts of your book and maybe synthesize, which is there is a system of legacy broker-dealers, the Goldmans, Morgans, and in Katsuyama’s case Royal Bank of Canada that is in the business of earning reasonably large spreads as market makers between where they can buy and where they can sell, when interacting with customers.

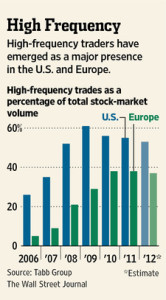

And then there’s this disruptive group of nerdy quants in flip-flops like you, who are getting in there, narrowing the spreads, and sort of stealing their lunch little by little. And in the course of doing that, in your telling, they’re profitable and also squeezing the profit margins of market making. So the real tension here is between legacy broker dealers and these new techy guys in flip-flops, – who are profitable, but really just at the expense of the legacy broker-dealers, the old Wall Street folks. Is that the right paraphrase of your version of what’s happening here?

Peter: I think it’s close. I was surprised when I heard Flash Boys was coming out, I thought that Lewis would love the story of a band of outsiders who had no experience on Wall Street. They came to Wall Street and made everything faster, efficient, more transparent. And as a result lowered the cost for everyone.

Michael: The high-frequency guys would be the Oakland As of Wall Street[2], right?

Peter: Exactly.

Michael: They’re cheaper, faster, quant-ey, numbers driven. They’re the plucky underdogs that everybody likes.

Peter: Exactly. I was quite surprised when I read the book and found out they had become the villains. That the underdog was in fact the old school on Wall Street. It is a bit more complicated than just the high-frequency traders versus a Katsuyama. There’s more at play here. Katsuyama isn’t exactly a market maker. He’s trying to work these orders into the market. He’s interacting with the market makers.

But I think his beef is overall with high-frequency traders as an explanation for why things are going awry. And why are things going awry for him? For people in that boat, there’s a lot of pressures that came to bear as the market started to change in the last decade.

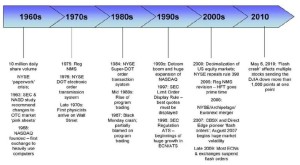

When you start to have Regulation NMS, a lot more exchanges popping up, a completely different mindset in terms of rules, and you have the electronification of the markets really taking hold, all those factors make it very confusing. It’s a lot of upheaval, a lot of change.

On top of that, and the real competition for someone like a big bank equity trader like Katsuyama, is that people are using computers to develop algorithms that would replace him. This is what he does in Flash Boys. He creates an algorithm called Thor that basically replaces his job function. He becomes a sales person for Thor instead of handling the orders himself.

But if you’re in his shoes in 2007 and you see all of the rules changing, these new electronic exchanges, computers becoming a much bigger factor, and then you see these algorithms for trading that are going to replace your job, it’s a really scary world.

The thing is it’s very hard to blame these algorithms like Thor. It’s much easier to blame some class of people, particularly if those people aren’t very well known and don’t have a very big voice. So you can blame the high-frequency traders for these changes, and you can say around the same time we started hearing about high-frequency traders we started hearing about computers in the market. Started hearing about more markets. And Reg NMS came out around the same time we were hearing about these high-frequency traders. They were there beforehand, but that’s when he’s hearing about them.

All these changes, I think it’s natural for them to try to find someone to blame. These are the people that they blame. But really, a lot of these traditional traders were displaced by a number of other factors.

There are also other traders who have survived and thrived. The complexity of the markets does not reduce their value in any way. In fact, one could argue it enhances their value. But you have to be someone who has embraced that complexity and you can tell your clients I know how to navigate this market, and there is still a role for a human trader who knows how to work this kind of an order.

Ironically at our own firm, if we had a large order of our own we needed to do for some sort of special hedge, we would have a human do it. We wouldn’t just program it into a computer. And I believe there’s a value for humans in the market.

Introducing IEX

Michael: So one of the major parts of Flash Boys, as well as in your telling, is the introduction of IEX, which is Katsuyama’s exchange. Is there something new about that exchange or is this just a solution in search of a problem? Meaning, if there’s no front running, and IEX is supposedly there to solve front running, is IEX doing something good? Is there something real there, or is it just a marketing technique?

Peter: I think I kind of agree with your characterization: “a solution in search of a problem.” Yes, and Lewis kind of sets up the entire book saying IEX is designed to prevent high-frequency traders from this front running scam. This will prove it because no high-frequency traders will want to trade on IEX. Now we’ve blocked them all from doing their front-running scam.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that on day one, the largest purchase on IEX is a high frequency trading firm. In fact, today a large portion of liquidity on IEX comes from high-frequency trading firms. I think that’s part of your answer right there.

However, as a solution in search of a problem, they actually have created a problem. If you ask most people, say nine months ago, are you concerned about high frequency trading, they’d say high frequency what. But after Flash Boys and IEX came out, suddenly this has become a problem people have to deal with. There were a lot of asset managers on Wall Street who then had to tell their clients whether or not they felt high-frequency trading was a problem for them, where never before did they have to explain that.

So now that there is this crisis of confidence that they themselves have created, they offer themselves as a solution to it. From that perspective, if they do give people confidence, then that does add value. I know it sounds strange.

Michael: A little convoluted.

Peter: Right. They created their own crisis, but if they solve that crisis by giving people confidence in the markets again, then that’s a benefit.

Positives of IEX – Transparency, and Order Types

Peter: Another positive about IEX is that they really trumpeted the role of transparency in dark pools. That goes a long way because one of the biggest concerns about dark pools is you don’t know what’s going on in them. It’s wonderful they have been able to bring that element back to the debate.

They also came out and said we want to have a limited number of order types. And basically the order types are what governs how your intentions are managed by a market center. They’ve gotten incredibly complex across all these market centers and the fear is that not only do people not understand them when they’re using them, and they could shoot themselves in the foot, but then also as you have this increasing complexity it makes the exchanges more likely to do something incorrectly.

And so IEX started off with a premise that they wanted to have a very few basic order types. I think that’s very laudable, to really try to simplify the process. Since then they’ve added a couple more order types because their customers have asked for it, but the principle still stands that the simplicity is best in terms of having a smoothly functioning market.

Michael: As an outsider I found the explanation of order types hard to follow. They were all new to me. The reasoning behind order types mixed with ‑‑ in the case of Lewis’s book – the order types mixed in with payments for order flow are pretty hard to understand.

In the absence of understanding we want to believe a conspiracy theory. That’s one of the hardest parts of understanding, both his book and then your book also in response to it, because I’m totally unfamiliar with the order types.

Peter: I struggle with how to explain those order types because they are complicated.

Michael: To get into why somebody would want a certain order probably requires many pages of explanation.

Peter: It does. It’s very difficult. You kind of nailed it when you said some people will just jump to conclusions. If it’s that complicated it can’t be good. I agree that many of these complicated order types aren’t good. What I don’t agree with is someone saying if it’s that complicated it can’t be good, and someone must have implemented this because of some evil conspiracy. It’s that last part that doesn’t follow from the first part.

It can be just complicated and not good because someone wasn’t thinking it through. That’s the case for most of these order types. That someone wasn’t thinking it through or they created one order type, and because of that it created another problem. And they needed another order type to solve that.

Michael: The analogy from my Wall Street experience is CDOs which are very complicated. But the people operating and creating very complex debt structures understand the waterfalls. It’s not not understandable. They’re specialists and they understand what they’re doing, but when you have a journalist describing what went wrong with CDOs, they decided it’s the complexity itself that’s wrong with it. Which is not exactly true.

But from an outsider reading that you go “Wow, so the complexity is the evil part.” No, actually it’s the leverage that’s the evil part. Or it’s the stuff that made the CDO that’s the evil part, not necessarily the complexity of it. That’s my analogy for understanding what you’re saying which is: these order types have a place, and there may be legitimate things about it. But it certainly appears as an outsider that there can’t be anything good with something that complex.

Peter: I would also say from an outsider in the CDO world, that the complexity becomes a problem when people employ that ‑‑ in this case employ a CDO without understanding what it does. Without someone explaining it to them correctly, so when they believe they have the correct explanation but they don’t.

I think with these order types, one thing that’s interesting is that the order types actually are explained correctly. All the order types are submitted to the SEC. There’s a filing that explains it. So they may be complicated but there is a clear description of what they do. If someone doesn’t understand them and they decide to use them, the burden was on them to actually look at it. The materials were out there. That said, it would be a lot simpler if you didn’t have them.

Dark Pools

Michael: I would like to know about dark pools because they’re completely opaque to me, so to speak. Why do institutional investors use dark pools? Maybe by background to the listeners, dark pools as far as I understand are usually set up by a hedge fund or broker-dealer, in which block traders get to anonymously trade and it’s “off exchange” I guess, is the key to a dark pool, so that the trades are not reported. Why would somebody want this?

Peter: Correct. In a dark pool none of the orders are actually broadcast. There’s no market data. You never see the quotes. You never know actually what the current market is in a dark pool.

That and the fact that ‑‑ there’s some regulatory oversight, but it’s much less than an exchange, so you’re not necessarily guaranteed to know how they match orders. They can tell you that, but they also might not tell you exactly what algorithm they used to match different orders. You can’t really review at the end of the day and say should my order have been executed or not; did I get the price I wanted or not.

Michael: You can’t compare it to the exchange.

Peter: No. So they don’t provide a lot of that data. That transparency isn’t there. The rationale for dark pools is that the public markets have a lot of people who are trading and they’re out to get an edge. Why don’t you come into this dark pool, our private group here. And hopefully you’ll be able to get the price you want.

In a way, it’s kind of remarkable that only on Wall Street could you have someone making the pitch saying you don’t want to do everything out in public where there’s full transparency, you can see exactly every single step that’s happening. Instead, why don’t you come back here in this dark alley with this bank? You can trust us. Just forget about all this stuff from the financial crisis. Trust us.

Michael: So you would say, and probably most people would say that within the dark pool there’s quite a lot less transparency, no price disclosure, and less regulation. So what’s not to love, I guess?

Peter: If you’re traditional Wall Street, what’s not to love.

Michael: So why do people want to use a dark pool? I don’t get that.

Peter: There probably a number of valid reasons. Part of it is the marketing pitch basically saying you don’t want to be in the public markets. And some people buy that because they like this exclusivity or they’ve been convinced that there is something in the public market that they should fear.

One selling point that is often mentioned is that in a dark pool you may be able to arrange larger trades. And so the idea is that in the public markets you have all these small trades, wherein the dark pool maybe you could say I only want to transact with other people doing these large blocks of trades.

That is true in a very small number of dark pools. The SEC did a study a while back and looked at 44 different dark pools. Out of those they found that only five of them had average order sizes of more than 1,000 shares. So when they looked at these dark pools they said 60% of all the orders that were entered into the dark pools were for 100 shares.

Michael: Averages are difficult. We could be fooled by averages. You could have a lot of small 100-share orders, and also a significant number of large-share orders.

Peter: That’s true. But they were saying average order sizes of 1,000 shares. I think that kind of indicates where they’re coming in on those dark pools. What I am saying for those five dark pools they do seem to be more biased or configured towards supporting these large transactions. To me, that seems like that could be a credible reason for having your dark pool.

The other dark pools seem a lot like any other market, only they’re less transparent and a little more exclusive. They may have their own tweak, or hook, here and there. IEX has its own little hook. But from a macro view you wonder “Do we really need to have 40 dark pools? Are they really providing value to our markets or does it take the public out of the public markets?”

Michael: In my experience, all of bond trading was over-the-counter, meaning there was no exchange and no price disclosure. But if I took a customer out to a really nice dinner, or we went to the Kncks game, he’s definitely doing a trade with me the next morning as a thank you. That’s our job as bond salesmen, to take the customer out and you will get ‑ at least in the short run ‑ you’ll get a thank you trade, or a couple of thank you trades, or a big order to work or something. Is that’s what driving dark pools, also? If I’m a Goldman equity salesman, do I take Putnam out to Cirque de Soleil and then I’m getting his trades through my dark pool?

Peter: That sounds plausible but it’s not something I can speak to. It’s not my side of the business.

Michael: It all seems like – having not been in that world – the downside of the dark pools would outweigh the upsides. What do I know? That remains mysterious to me.

Peter: I can tell you we were always reluctant ourselves to trade in dark pools. I don’t know what that says to you but the high-frequency firm, that was not our preference to trade in dark pools. We were very reluctant to enter into dark pools, for all the reasons I mentioned.

Maybe we were being overly cautious, but to us it just seemed like there were a lot of risks going to a place where we couldn’t see what was going on.

Michael: In Lewis’s telling, within the dark pools it’s rife with high-frequency traders who are sniffing out big block trades that they can essentially front run through small trigger trades, where you lay out a little trap, and that trap ‑‑ which you’ve said is basically impossible, you can’t judge the size or magnitude of these orders through these trigger trades. But that seems to be a big part of Lewis’s contention which is this is a great place for high-frequency traders to deviously figure out who’s trading, in what size, and how they’re doing it, and therefore anticipate and get in front of it.

Peter: Right, and the trigger trade idea is even more comic because in the book they’ve had this hypothesis about these trigger trades. They call them bait, 100 shares. Then finally when they launch IEX they see these 100-share orders coming in there. And they say aha, we found evidence of this bait. It turns out it’s a bank that’s sending those orders in there, not a high-frequency trader.

The remarkable thing to me is the next paragraph in the book doesn’t say “And then they realized that perhaps their theory was incorrect.” Instead, they come up with other theories about the bank must be doing that intentionally to harm IEX or something like that, or to make IEX look bad.

The SEC said that 60% of all the orders going into a dark pool were for exactly 100 shares. So if 60% of all the orders you’re receiving are supposed to trigger some front-runner to go off and buy 100,000 shares, it’s going to create chaos. It’s more than half of the orders coming in there would be this bait that they’re talking about. It’s ridiculous.

Michael: You can’t imagine a scenario under which firms that are situated like your firm could ever make money doing that?

Peter: If that were the case that these 100-share orders really did trigger a front runner to go out and buy 100,000 shares, you would see a pattern in the market and it would be very clear. 100 share order, 100,000 shares purchased. You don’t see that. You would actually see 10,000 times more volume in the markets. You don’t see that. It’s pretty obvious when you look at the data.

The Impending Blowup?

Michael: One other big thing that is my biggest fear about high-frequency trading or algorithmic trading which is that I have a theory which seems to be borne out by history, which is that financial innovation always runs faster than financial regulation. And that most of the blowups we see in the markets, which eventually affect the economy are some instance of really smart innovative people doing things that regulators, and common-sense, and risk-control people can’t anticipate.

The blow up will be a function of the new market structures or new financial technology. And I see algorithmic trading as the last 20 years has taken over, and yet I suspect we don’t really know what happens when it gets out of control. That’s my not particularly informed view of the Flash Crash, and that’s my big worry about this industry. I’m worried about complete catastrophe, in milliseconds or seconds, without humans being able to stop it. And the ’87 crash was some version of this where people had bought computer-driven portfolio insurance and the thing crashed almost on not something particularly fundamental. Do you worry about this also or is this just me and my paranoid, don’t really understand computers, saw too much of the Terminator movies? Am I a whack-job when it comes to this fear?

Peter: Not at all. I think you’re right that financial innovation does often come ahead of regulation.

I think you are spot on. That is a concern we should all have. It’s healthy to have that concern. That should always be a concern that’s driving all of our views of market structure. The SEC should have that concern, and they do have that concern. Market participants should have that concern. It should be something we’re always looking at.

The equities markets are very interesting because we actually do implement a lot of changes into the equity markets and they tend to have stuck more than other areas of the financial industry.

As you pointed out in your blog, the few reforms we made in the housing market are already getting rolled back. But since the equity problems we had, like the Flash crash in 2010, there have been a lot of changes. They keep layering on additional changes.

Not only did they implement more circuit breakers, not only did they say we need to focus more on improving our technology; we need to improve communication among the exchanges, make sure they’re more consistent in their policies; they focused on the broker-dealers too.

They said you have to have risk controls in place. Now the SEC has proposed yet another set of regulations that mandate the type of testing that you have to have for these systems. There’s a lot going on to try to make sure that these problems don’t occur, or if they do occur they’re going to be limited in scope. And I think that’s one of the very interesting things about the equity market that there are problems that occur. But those problems are all very limited in scope.

It’s really interesting to see how robust the market is right now. When you do have a problem on a particular exchange, the markets ‑‑ you have all the other exchanges. All the other exchanges can provide liquidity. And so the market actually is much more robust than a lot of these other markets where you have only a single-liquidity or only a single place where you can do your transactions.

Michael: You have this built-in multi exchange, built-in backup exchange at all times versus my fear which is everybody makes the same risk-control errors or misses the same innovative technology problem at the same time. So when that problem – whatever it is – happens, everybody is caught off guard. You’re saying multiple changes, each slightly different and stands on their own. We’re not going to face a breakdown of every exchange all at the same time, or every market maker at the same time.

Peter: Correct, the diversity of exchanges, the diversity of market makers ensures you’re not going to have everything break down at the same time. But if you do, the interesting thing is that there are also a lot of controls built into the market now to pause trading. We’ve learned from the mistakes of the past. We said if that does occur are you going to pause trading. And people will reevaluate and they’ll see what happens.

It’s unfortunate we had to learn the way we did, but we’ve internalized a lot of those lessons and so if a particular firm does screw up you’re going to have the market pausing, figuring out how we’re going to deal with this. That firm will go out of the market, and the market will recover.

Michael: It’s a pretty optimistic view. I remain frightened but I agree ‑‑ the most optimistic view that I have is company firms like Knight Trading, which famously kind of went out of business shortly after some bad programming and errant trades that went wrong. They get e

liminated and the survivors are the ones that have risk controls, and do know how to slow down or turn off their algorithms at the right moments.

Some trust, because I’m not close to it like you are, that the various circuit breakers or regulatory changes even in the past few years are going to prevent the next big one. But I’m so far from understanding that or having the updates, that I just sit, and ponder, and get scared. But I take some comfort in if you’re close to it and you’ve met with these regulators, and you follow the industry, and you think it’s pretty darn good. And there’s a learning process going on, that we’re responding positively to shocks and mini crashes and that kind of thing.

Peter: I think there is a learning process. There is some optimism involved. You can never predict the future 100%. But the very encouraging thing is that it’s not just that we’ve learned from things that happened in the past, but that we’ve learned in multiple ways. There are multiple fixes in place due to the errors that we’ve seen. When we see a new error, people are very vocal in the markets, and they demand a fix for it. That fix comes. It might not come as quickly as they want but it comes. And we have a lot of layers of protection in the market.

Michael: A reason for optimism.

[1] Actually about a year ago, I’m just slow to post podcast interviews sometimes.

[2] Everybody should of course read Michael Lewis’ Moneyball, which we are referencing here, and which is awesome.

Please see related posts:

Book Review of Flash Boys by Michael Lewis

Book Review of Flash Boys Not So Fast, by Peter Kovac

Book Review of Inside The Black Box, by Rishi Narang

and audio interviews:

Peter Kovac, Part 1 – HFT Profitability, Front-Running, Market Making

(and upcoming) Peter Kovac Part 3 – Cheating and Morality

Post read (173) times.