Would you like to understand where Mitt Romney’s economic ideas come from?

Would you like to understand where Mitt Romney’s economic ideas come from?

As soon as Edward Conard hit the book-selling circuit with Unintended Consequences: Why Everything You’ve Been Told About the Economy Is Wrong , I started to get messages from my reliably liberal friends. Conard made the cover of The New York Times Magazine, – with the arresting headline “The Purpose of Spectacular Wealth, According to a Spectacularly Wealthy Guy” – and he made an appearance on The Jon Stewart Show, two hostile environments in 2012 for a former Bain Capital partner, apparently preaching an updated version of Gordon Gekko’s “Greed is Good” speech.

, I started to get messages from my reliably liberal friends. Conard made the cover of The New York Times Magazine, – with the arresting headline “The Purpose of Spectacular Wealth, According to a Spectacularly Wealthy Guy” – and he made an appearance on The Jon Stewart Show, two hostile environments in 2012 for a former Bain Capital partner, apparently preaching an updated version of Gordon Gekko’s “Greed is Good” speech.

“You have got to review this book and tear this guy apart,” my friends urged, and I promised I would.

Suspecting I would not want to own the book, I put in a request to borrow it from my local library, only to endure 2 months on the waiting list before a copy became available. Meanwhile Unintended Consequences hit the New York Times best seller list and Conard went on to represent the Bain Capital perspective all up and down the cable television circuit. Unintended Consequences finally became available at the library at the end of the summer, and I read it over Labor Day weekend.

My dear liberal friends, I have a confession to make: I like this book quite a bit.

I’m not saying you need to go out and buy it, as I’m sure you will not. But I am saying the guy has made a serious and effective effort to represent the Mitt Romney view of the world, one which has an internally consistent logic, if you agree with his assumptions.

Let me start by describing the part of the book I really liked, followed by the part I liked pretty well, and then I can finish with a critical flourish that I expect will return me to the good graces of my liberal friends who recommended I review it in the first place.

Conard organizes the book in three sections, “What Went Right,” “What Went Wrong,” and “What Comes Next,” sections which may otherwise be described as Past (1950-2005) Present (2006-2012) and Future (beyond 2012). In summarizing my views of the book: I loved the Present; I liked the Past; and I plan to get a little snarky in the Future.

“What Went Wrong” – The Mortgage Crisis

I’ve invested a significant portion of my working life in the mortgage finance industry, first as a mortgage bond salesman, then as a hedge fund investor purchasing consumer debt including mortgages, and most recently as a self-appointed commentator – blogger – on the Credit Crisis and Great Recession trying to figure out causes and effects that stem from the mortgage market blowup.

As a result of my professional past, I cannot state strongly enough how much it bugs me to read terrible analysis from otherwise respectable journalism sources about what went wrong with the sub-prime mortgage market and the Credit Crunch.

If most journalists get the mortgage story 50% right and 50% wrong, Edward Conard gets it about 90% right, and for that fact alone I am grateful for his book. In debunking a significant portion of the equine urine that passes for our national sub-prime mortgage narrative, Conard earns my gratitude.

Forthwith, some mortgage market narrative myths Conard helps debunk:

Predatory bankers frequently tricked people into taking out loans that they could not afford to pay back. Um, no. This is not a real world banker strategy, to lend money to people who cannot afford to pay back the loans. It’s just not. It’s illogical to believe most bankers seek to make bad loans, and it drives me nuts to read this implied or stated by otherwise intelligent writers. Bankers in the real world make loans to people they believe will pay them back. In the run-up to the most recent crisis, Wall Street mortgage bond structuring departments and mortgage investors mistakenly believed rising home values and low interest rates would help sub-prime borrowers refinance before they defaulted – a pattern that only worked for a short while – but it was a mistake, not a conscious predatory strategy.

On the other hand, I have dealt in my investing business with many predatory borrowers, people who took out mortgages they knew they could never pay back, but who hoped to get lucky with real estate price appreciation or who hoped to delay the foreclosure process long enough to keep a house for free while they defaulted on their debt obligations. That scenario happened to me in my investing business almost too many times to count, but I never once met a banker who sought to make a loan that couldn’t be paid back. It’s bad for business. Banks that make loans that can’t be paid back go out of business quickly.

2. Wall Street Banks, in a conspiracy with the rating agencies, duped mortgage bond investors in the run-up to the crisis. Not even close. While it is true – and Conard acknowledges as much – that there’s an imbedded conflict of interest in the fact that rating agencies get paid by Wall Street to rate their products, its equally true that mortgage bond investors are among the most sophisticated financial analysts found anywhere. They were, and are, hyper-aware of exactly who pays whom. Mortgage investors know what massive grains of salt need to be applied to rating agency information. Just because journalists and politicians recently discovered the role ratings agencies play in the investment world does not mean mortgage investors needed them to discover that role for them. It’s a known Wall Street truism, which I stated before and will state again as long as I need to: Professional investors never react to rating agencies moves, and professional investors understand the limitations of bond market ratings.

3. CDOs and other mortgage derivatives became so complicated that they were bound to blow Wall Street up. A common journalistic conceit in describing bank losses due to CDOs and the alphabet soup of other mortgage bond structures (RMBS, ABS, CMOs, CMBS, IOs, and POs to name a few of the more common ones) implies that the opaque nature of structured products doomed them to failure. Not true. Just because a journalist does not understand the product does not mean that the structurer, trader, and mortgage investor do not understand the product. The mortgage bond desks of Wall Street firms and of bond buyers make it their job to understand their products.

Some mortgage derivatives, CDOs in particular, suffer from a chronic lack of liquidity, for which in ordinary times the market demands compensation, in the form of higher yields. In the Credit Crunch of 2008, CDOs and other structured products became untradeable at anything like fair market value. They are terribly illiquid, not terribly complicated, for professionals who traffic in structured mortgage products.

In addition to effectively debunking some myths of the causes of the Credit Crunch, Conard gets the story right in a few other respects, namely:

- The optimistic policy begun in the Clinton era of encouraging expanded home ownership through low-money down loans had the unintended consequences of kick-starting a doomed boom in sub-prime lending.

- The run on liquidity throughout the crisis was far more consequential in destroying financial firms than any realized losses actually suffered by banks and insurance companies. In other words, the panic was worse than the ultimate defaults.

- Credit Default Swaps (CDS) per se were not the cause of financial system distress, nor are they inherently anything more than risk transfers between counterparties, like buying or selling a bond or loan.

In sum, Conard builds up a lot of good will with me by getting the causes of the Credit Crisis essentially correct, or at least far more correct than I’ve read in other books and journalistic narratives.

“What Went Right” – The US Economy, 1950-2005

In this section we begin to see daylight between Conard and me, although not because he’s necessarily wrong, but rather because we have different starting assumptions.

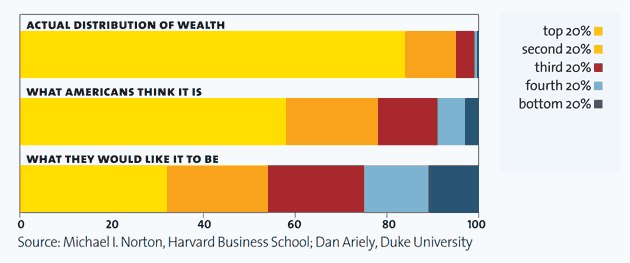

Conard became such a target for liberals with the publication of Unintended Consequences for his unabashed celebration of massive wealth concentration for successful business people. He sees inequality as a natural consequence of a difference in people’s work ethic, their innovative contribution to economic progress, and what he terms ‘lucky risk taking,’ by the entrepreneurial and investor classes. As a Bain Capital partner, he and his book represent to liberals the ultimate voodoo doll for Romney-bashing in an election year. We’ve seen enough of Romney’s comments on and off the record to believe that there’s considerable agreement between Conard and Romney on this view.

I have issues with the Conard/Romney world view, but I want to be careful to point out what I like about Conard’s argument. His ultimate concern, clearly stated, is growing the total amount of economic output in the most efficient way possible. He believes that incentivizing people and institutions to maximize economic output – via financial gain – is more effective than anything else at producing a growing economy. Impediments to economic growth, in the Conard universe, include taxes, business regulations, trade restrictions, and income redistribution payments, each of which he believes lead to lower economic output over time.

Now, while Conard does not prove his assumptions to be true, they all strike me as logically correct. I too believe that each of those factors leads to lower economic growth.

Where we differ, and where I expect my liberal friends will gather around me again in support, is whether maximizing raw output in an economy is the single most important goal. I happen to believe that inequality of income and wealth outcomes have quite a bit to do with whether an economy is ‘successful,’ and have quite a bit to do, as well, with whether my society is the best it can be. At a certain point, I would trade some GDP growth for a bit more justice in the world, and I might choose a societal safety net now at the expense of a marginal innovation in computer processing.

Conard consistently advocates the economic growth path over the economic justice path. Before I paint him in overly simple terms, however, I think it’s worth returning to the Conard argument on its own merits, to appreciate it for what it is.

I find his argument entirely credible, for example, that our choice of wealth distribution via transfer payments dooms us to a lower growth path as an economy as a whole. I believe him when he argues that taxing the wealthy, who allocate an average of 40% of their income to economically productive investments, will leave less capital available for innovation, production, and economic growth. I agree with him when he states that in a global economy of efficient markets the unionization of US workers will quickly lead to offshoring of those jobs on the one hand, and higher consumer prices on the other.

One Conard argument about the success of the US economy in recent years stands out when compared to Europe and Japan. He notes that in the last two decades of innovation in computers, software, the internet, and social media, the United States essentially ‘ran the table’ when it came to all of the most important businesses. Citing “Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Intel, Apple, Cisco, Twitter, Amazon, eBay, YouTube and others,” he highlights the US economy’s investment climate and rewards for risky innovation as a differentiating factor compared to the rest of the developed world.

In sum: I believe Conard when he argues for the factors that lead to higher growth of an economy overall. I don’t want to live in that society, but I do think it’s useful for people who disagree with the Bain Capital model to think about what they’re willing to give up to live in a different type of society. Are you willing to be a little bit poorer?

What Comes Next – Conard’s Future

In the third part of Unintended Consequences I have to part ways with Conard entirely. I can’t endorse his prescriptions for the economy, in part because I don’t agree with his view of growth vs. equality, but also because he begins to reveal a curious coldness that hurts his arguments.

In the wake of the Credit Crunch, Conard argues not for regulating banks more but rather for enduring bank runs like we experienced in 2008 since “The Crisis also reveals that the cost of government guarantees, excluding the future cost of moral hazard, was near-zero. In fact, the government expects to turn a profit on the assets it bought to mitigate withdrawals in the Crisis.” Notably absent is his reckoning of the cost in human terms or non-government costs of the financial wipeout for so many.

Conard also displays a curious tick in his thinking – and his writing – of quickly taking any government imposed limitation (taxes, regulations, unionization, trade restrictions) on individual or corporate wealth and translating that immediately into “even more lost jobs and higher consumer prices.” As I review his book, he appears to do this every single time. Anything that affects the rich and upper classes, in Conard’s description, has an opposite and larger detrimental effect on the middle and lower classes. The first few times he does this I’ll acknowledge that, yes, some government interventions may have unintended consequences in other areas. But when Conard continues to say it every single time I’m left thinking – ok, I get it, higher taxes on your Bain Capital folks is just going to bite the rest of us even worse every single time, in all cases. Unfortunately, by applying the same response to different situations his opinions appear less evidence-based and more economic dogma-based.

My final thought about Unintended Consequences is that’s it’s curiously devoid of any personal or professional anecdote. Conard worked for Bain Consulting, Wasserstein Perella, and then finished his career as a partner of Bain Capital, running its New York office. Surely Conard accumulated not only material wealth, but a wealth of interesting business stories with which to illustrate his logical, yet dry, economic analysis? But Edward Conard, the person, is curiously absent. So where are the people in Unintended Consequences? Ultimately Conard’s book describes a mechanized world of efficient human economic units, each maximizing their own utility for private gain.

What does Conard think of people who don’t fit this dry, efficient world? In his own words: “A shortage of talent exists, in part, because a large number of college graduates refuse to take the risk and responsibility necessary to bring unrealized investment opportunities to fruition. Art history and Elizabethan poetry don’t employ workers; the arduous and tedious application of business sciences such as computer programming and accounting does.”

Ok, then.

If you would like a country with higher economic output and more wealth for some people, “Vote Romney/Ryan 2012!”

However, if you would like a world with a bit more poetry in it – and a measure of social justice – you may want the other guys.

Please see related post:

Book Review: The Upside of Inequality by Edward Conard

All Bankers Anonymous Book Reviews in one place.

Post read (10391) times.