How’s inflation going these days?

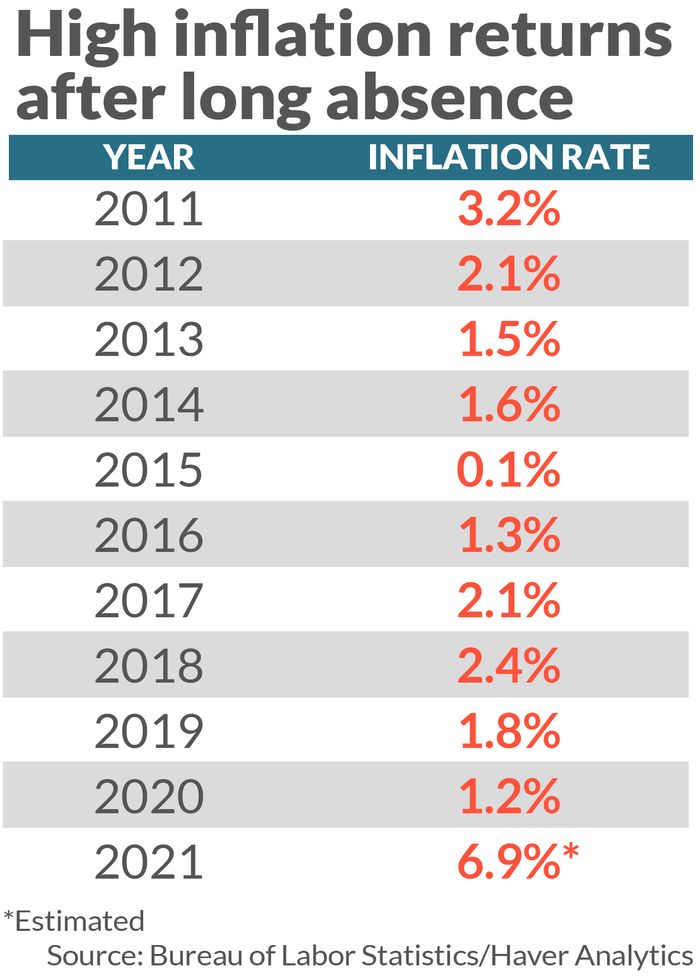

It was the talk of the town 6 months ago and 10 months ago. The most recently published April 2023 Consumer Price Index rise (the most commonly quoted inflation rate) was 4.9 percent annual, down from the peak 9.1 percent annual rate in June 2022.

Even as the world panicked last year about rising inflation, I will now share with you a teensy confession. I didn’t really see it. Or if I did see it, it felt fine, temporary, non-threatening. I know this is heretical and borderline obnoxious to say.

This week I came across a comment on inflation from the finance writer Morgan Housel, who is one of the very best at what he does.

“What I think is really interesting is that everyone spends their money differently. So no two people have the same inflation rate,” he said in an interview in September 2022. “There is no such thing as the inflation rate. It’s just your own individual household.”

Housel’s insight explains my reaction when compared to the collective freakout I noticed elsewhere. My experience of inflation is different from yours, and yours is different from everyone else’s.

Falling Prices

Now in the latter-half of my intended century on this planet, I could settle gently into the “kids, when I was your age, that used to cost a nickel” phase of my life. But as I look around, that story isn’t particularly true in many areas.

In July 2013 I purchased an Apple Macbook Pro laptop computer for the retail price of $2,499. This past week, the monitor died and I returned to the Apple store in the North Star mall and bought another Mac Pro laptop. In my mind, 10 years for a laptop is a good run. It lived a good long life as far as electronics go and it was time to buy a new one. I paid $1,999 retail for the new one with improved graphics, larger memory and a decade worth of incremental feature improvements compared to the 2013 version.

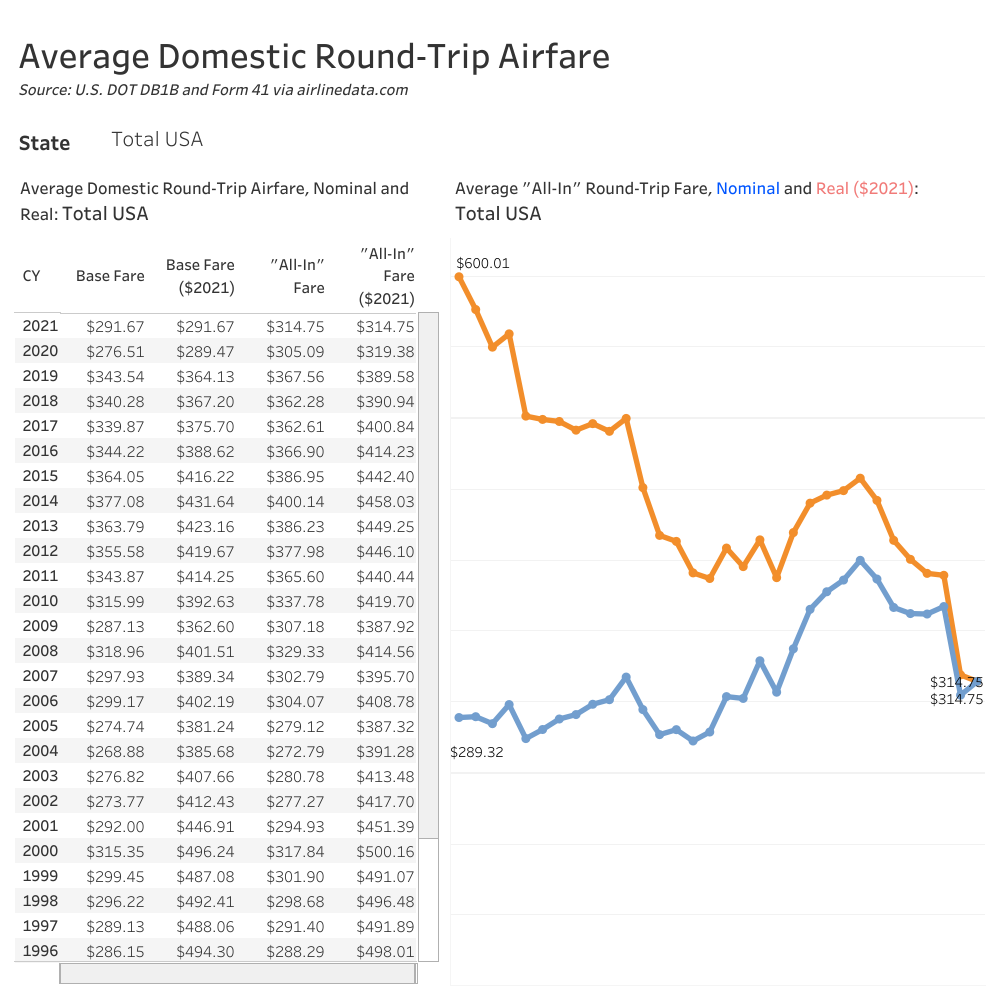

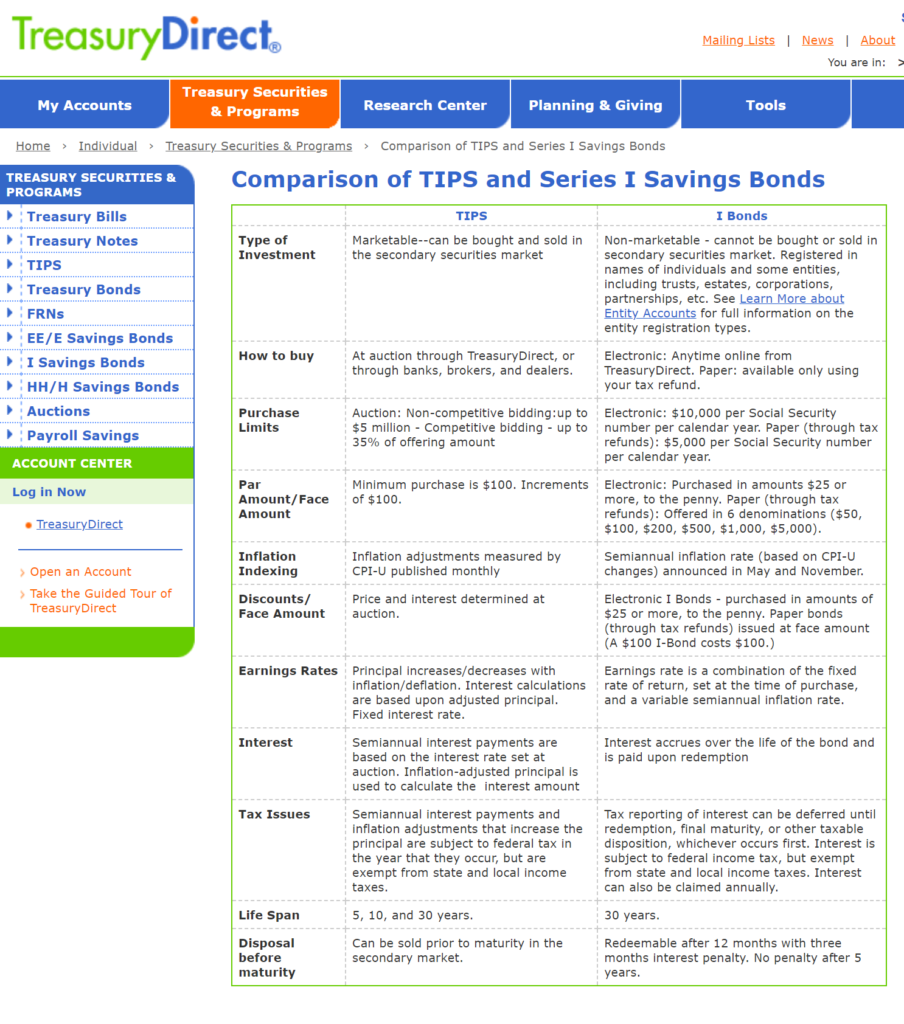

Last week I booked a round-trip flight to New York City in June for the all-in price of $517.80 (including taxes, travel booking, and airline fees). How much was this flight to New York City 33 years ago? I can’t compare the exact flight but The Department of Transportation reports that the average domestic airline fare from Texas in 1990 was $253.41. Meanwhile the average domestic round trip fare in Texas all-in was $314.75 in 2021.

Depending on the reference years, the average domestic flight costs the same, a little more, or a little less, over the past 40 years. This is actually incredible.

This past winter the internet lost its mind over the price of eggs, which had doubled. (Avian flu had wiped out the hens.) Our collective hive mind pointed to the rising cost of a carton of eggs as if that were some sign of inflation end-times. The price for a dozen large brown cage free eggs from HEB is $2.78 as I write this in mid-May 2023. Pretty much unchanged over the past decade.

I mention computers, flights, long-distance phone calls, and eggs because we notice the rise in prices but rarely their fall. So that’s one piece of the puzzle.

Inflation that we welcome

If you are a capitalist, inflation maybe hits differently. In my own capitalist way of thinking, the rise in both stock market values in my retirement portfolio over a decade and in the value of my home over that same decade are forms of inflation. Benign forms, from my perspective, but inflation nonetheless. Future purchasers of my shares or my home are negatively impacted by that inflation. Still, I’m personally glad for it.

Bloomberg News has run stories this year about companies that engage in “excuseflation.” That means firms that use bad news, like supply-chain disruptions or shortages or war – those were the top 2022 excuses – to raise prices. Companies that can raise prices and keep them high when normalcy returns – without losing market share – then have the opportunity for higher profits.

Investors, in turn, seek to purchase shares in companies that prove they can hike prices and expand margins. This is another way in which inflation hits differently depending on who you are. For owners of capital, price hikes by companies are a sign of strength and an incentive to invest. For homeowners, price hikes are a path to long-term wealth.

Inflation I don’t notice

I’m never going on a Caribbean cruise, where prices are up 14 percent since last year. I work from home, so I am not hurt much when gas prices hike the cost of a daily car commute. I don’t rent my home, so I’ve avoided one of the most brutal rises in costs in recent years.

Now, you’ve probably noticed I have conflated three ideas. First, prices are flat or falling in many areas over the past 30 years. (televisions, computers, long distance telephone calls, plain t-shirts and socks). Second, I benefit from some price hikes (my real estate, stocks in companies that have pricing power to use inflation as an excuse to hike prices and increase their margins.) Third, some price changes I don’t stress about because they hardly affect me directly (gasoline and diesel fuel, cost of caribbean cruises, home rental prices.)

I’m not saying inflation isn’t real. I’m saying our experience of inflation is unique to each of us. There is no objective inflation since we all buy and own different stuff.

My inflation experience is about to get worse

One of the worst areas of inflation over the past 30 years has been the rising cost of higher education. Since I will be paying for this over 8 of the next 9 years for my daughters, you can expect near-constant whining in this space about tuition inflation. It’s going to be brutal. For me to experience and for you to read about.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

Book Review: The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel

Post read (41) times.