I’m a markets guy who believes in applying economic principles to situations requiring innovation and the allocation of scarce resources. Which probably explains why I think it’s so important to also point out the hard limits to markets. There are big downsides and limits to thinking like an economist. The COVID-19 vaccine development and rollout is case study for examining what free markets are specifically not useful for.

“Health care should be run more like a private business,” is one of the more misguided statements that well-meaning people like to make, up there alongside the equally misguided “schools should be run more like a private business.”

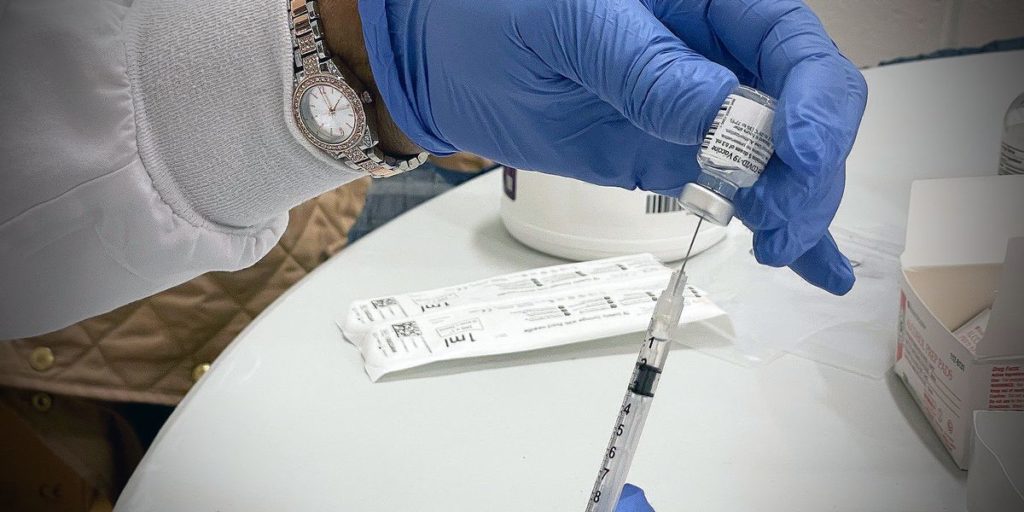

The miracle of this vaccine development and initial rollout in one year’s time can not be understated. This is an unprecedented scientific achievement. It should be understood not as a victory of market-based economics, but rather the opposite: the extraordinary application of central government planning. Sometimes, in the good old US of A, we forget this point.

The Trump administration made the correct call last Spring to directly fund six different private pharmaceutical companies to research, test, and manufacture vaccines. This initial $10 billion federal government investment – called “Warp Speed” – allocated in March 2020 was upped to $18 billion by October 2020. A seventh company, Pfizer, did not receive funds for research, but did receive a guaranteed order for 100 million doses. By guaranteeing demand for hundreds of millions of doses, the federal government induced pharmaceutical companies to essentially ignore market signals like risk, profit, and loss. The Warp Speed program understood that some unproven vaccine products might not work, and that hundreds of millions of manufactured doses could be wasted. And that was ok.

Markets are great for some things. But they would never have achieved this vaccine miracle in one year. Vaccine development driven by the private sector historically happens in the five to fifteen year time frame, but we obviously did not have that time. Pharma companies with an unproven product and uncertain demand would never have ramped up to manufacture enough doses by early 2021. The federal government – everybody’s favorite punching bag – made the correct choice to pay for it anyway, in the interest of speed.

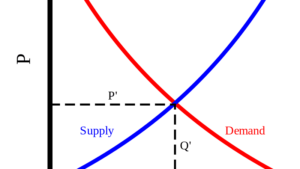

That’s how vaccine research and manufacturing was not left to the free market of efficient supply and demand signals. Now, when it comes to getting shots in arms, again we see the limits of economic-thinking.

For the next few months of the vaccine rollout we face a classic economics problem: too much demand and not enough supply. To vaccinate 80 percent of the US population we need more than 250 million doses (or actually double that, as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines each require two shots.) For now, however, we’re living the reality of severe shortages, crashing websites. Unavailable appointments and online signups that get filled within 6 minutes of opening. High anxiety.

The vaccine is free. But there’s not enough of it. Many of us expect to be waiting 3 or 6 months to get it. In the midst of severe scarcity, it feels like society is on a knife’s edge right now, looking for signs that some people are cutting the line. Who is using their money, or privilege, or network to get what other people need?

The “markets” solution to a situation like this – in a different context – would be to allow prices to determine who gets the scarce thing. That is clearly a moral monstrosity. In the coming weeks, the media will cover the issue of what celebrity, rich person, or government official cut the line to get the free, but scarce vaccine. But we all understand that a market-based solution to vaccine rollout – “who can pay the most right now?” or “who has power and influence?” – is morally abhorrent.

Looking forward a bit to a few months from now – hopefully in three months but possibly six months from now – we will have the opposite economics problem related to the vaccine. Too much supply and not enough demand. I’m referring to polls back in December in which only 42 percent of Texans indicated they would sign up to get a vaccine. Soon we will have plenty of vaccine supply. But if a large plurality of Texans and Americans decline to get it, we may be unable to achieve the 80 percent herd immunity that public health experts say is necessary to stop the pandemic entirely.

How would an economist solve that problem? I asked economist Robert Litan from the Brookings Institution, who has argued for substantial payments to induce vaccinations to get us more quickly to herd immunity. He says we should pay people a lot.

“I think if you tell people $1,000, and then especially for a family of four, that’s $4,000, you’re talking real money. And I think at $1,000 you could get [anti-vaccine] people to switch,” he told me. He even had a clever finance-based incentive to encourage speedy vaccinations within society. Litan proposed that all citizens would be given an amount like $200 up front, with a promise of the $800 remainder when the United States as a whole achieved 80 percent vaccination.

As Litan explained, “So what that does is it gives tremendous incentives to tell your friends, whether in real life or on social media, to go out and get the shot, because then we can all get the money.”

For my part, I loved his idea. It would get herd immunity results fast. It uses “market incentives” as a carrot to induce desired behavior. The $300 billion or so it would cost would be a lot cheaper than the massive and complicated federal bailouts we’ve already resorted to.

Medical ethicists, however, hate this idea. Although small payments would be appropriate for convenience’s sake – such as transportation or a small snack – large payments on the order of magnitude suggested by Litan would be considered coercive. It is apparently not ok to force people to choose between putting something in their body – however safety tested we believe the vaccines to be at this point – and a large payment like $1,000. So we have important ethical limits to applying an economic or markets perspective to the conundrum of vaccine rollout.

In sum, when it comes to our health, economic efficiency is not the right watchword.

Fairness and health outcomes are better guides. Enjoy your Socialism, everybody.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Post read (118) times.