How do mortgages make it to Wall Street anyway?

None of the following is essential to understanding mortgages from a personal finance standpoint, I just thought the details of mortgage securitization and mortgage bond trading and structuring would be interesting for some people.

I sold mortgage bonds at Goldman for a few years in the early 2000s, so this sausage-making was my daily life. Below, and in a subsequent post, I introduce some Wall Street concepts of the mortgage bond market.

- “When Issued” forward-trading of mortgage origination supply

- The packaging of homeowner loans into plain vanilla mortgage bonds

- The role of mortgage servicers and mortgage insurers in the bond market

- The demise of the big mortgage insurers in 2008

- The basics of mortgage trading – Prepayment risk!

- The basics of CMOs – mortgage derivative structuring

- Recent market moves must have caused a bloodbath on most Wall Street mortgage desks

In this post, I’m going to describe points 1 through 3.

Subsequent posts will describe points 4 through 7.

Conforming mortgages, the forward trade

In July 2013, Wall Street is now “forward trading” the October 2013 30-year 4.0% mortgage bonds. October 2013 mortgages are part of the ‘When Issued” market, which is kind of like a grain farmer selling wheat on the commodities exchange 3 months before his harvest. The farmer has an approximate idea of what yield he’ll get soon, but he may trade on a commodities exchange as his estimate changes, and as his sense for the attractiveness of prices changes.[1]

As the largest originator in the US, Well Fargo, in recent times, originates over $100 Billion in mortgages per quarter.

That means that on any day in July, and in fact for the next two months, mortgage traders at a big mortgage originator like Wells Fargo will call up their salesman at Goldman Sachs and ask Goldman to purchase some amount of their mortgages that will be originated by October 2013.

This “When Issued” mortgage market is just about the most liquid market in the world, and a $1 billion trade happens in seconds.

“Hello, this is Goldman,” said in a shouty but efficient voice

“Bid 750 Fannie 4s in October!” *

“22+” **

“Done” ***

“Done. GS buys $750 million Fannie 4s in October at 100-22+. Thanks for the trade.” Click.

****

[And…let’s translate:

* Wells Fargo today, in July 2013, is selling $750 million worth of future mortgage supply, which it will ultimately originate in October 2013. Wells has an idea of its future October volume, however, because of the recent amount of customers who have locked in their current interest rates. Many of these will end up as loans eligible for inclusion in a Fannie Mae securitization of similar mortgages.

**The mortgage salesman’s price is a fractional short-hand for how many 64ths Goldman will pay, in this case the 22+ means 22 and a half/32nds, or 45/64ths, or .703125. This quote assume everyone knows on the buying and selling side knows the ‘handle,’ which is the main price, near par, that the bond will trade at during origination. Newly issued mortgage bonds, like most newly issued bond generally, will trade somewhat near 100, but during periods of rapid interest rate changes this handle could be in the 95 to 105 range. The Well Fargo trader and Goldman salesman will now ahead of time and won’t waste time reviewing this info, until after the trade is done.

***I agree to your price. Not only that, but I agreed to your price so quickly (within a second or so) that you as broker are held to the price even if the market moves against you in the subsequent 10 seconds, or minutes, or days. Goldman is now at risk as a future owner of $750 million in bonds

****Ok, I bought your bonds.

Now back to your regularly-scheduled description of mortgage origination and hedging.]

As Wells Fargo’s mortgage origination supply fluctuates between July and October, Wells may find itself needing to sell more ‘When Issued’ mortgages, or it may buy some back if its mortgage origination supply drops. If mortgages expected to close in October instead actually close in November, then Wells may end up selling fewer mortgages in October and will instead do a trade so that it can deliver them in November.

Delivery, again, is like the futures market for wheat.[2] The farmer, in this case Wells Fargo, anticipates his yield, and manages and hedges his future production by selling his ‘When Issued’ mortgages to Wall Street.

Delivery and Securitization

When October arrives, Wells Fargo delivers its $750 million in conforming[3] mortgages to Goldman. Goldman may then choose to turn over this inventory of raw mortgages to Fannie Mae for securitization as a 4% Fannie Mae bond.

Securitization, the process by which a few thousand similar-vintage mortgages become a tradable bond, is the process that occurs to most home mortgages, further separating the home owner from the bank. Not incidentally, it’s part of what makes our home mortgage rates so affordable.

Let’s say for simplicity’s sake that 2,000 different mortgage loans underlie the $750 million securitization, for an average loan balance of $375,000. They will cluster in interest rate, to the 2,000 homeowners, around 4.375% to 4.5%, and all will generally have ‘closed’ in October 2013. Astute readers will notice the extra 0.375% to 0.5% difference between the homeowner rate and the bond rate. This difference largely gets paid in monthly fees to two different entities, the mortgage bond servicer, and the mortgage insurer. I’ll next explain these two roles in the mortgage securitization market.

The plain-vanilla Mortgage bond

Once the 2,000 underlying mortgages get grouped together and assigned to a structure, and assigned to a mortgage servicer, and guaranteed by the mortgage insurer – Fannie Mae – it becomes a tradable bond. The bond will get registered, with a Cusip and ISIN[4], loaded into Bloomberg for ease of tracking, and assigned a Fannie Mae number. I’ll call this one “FN 8720331.”

Let’s say Goldman next sells this particular FN 8720331 to a Vanguard Fund dedicated to purchasing new mortgage bonds. For the next few years, the Vanguard Fund will receive a combination of principal and interest from FN 8720331.

FN 8720331 is a AAA-rated, safe security. Vanguard will earn 4% on its investment – I’m assuming that’s the coupon of the bond and that it was purchased at par – although the timing of payments is uncertain. If interest rates decline from here, many of the 2,000 homeowners will refinance before 30 years, shortening the ‘average life’ of FN 8720331 to something in the 3 to 7 year range. If instead interest rates rise – as seems more likely – homeowners may realize their 4.5% mortgages is a great rate, and they may not refinance for many years. FN 8720331 may end up as a 10+ year average life bond. Vanguard takes that risk, known as pre-payment risk.

Mortgage Servicer

The mortgage bond servicer earns its fee – a portion of the 0.375% to 0.5% difference between homeowner interest and bond-holder interest – making sure that the monthly mortgage payments of 2,000 homeowners get routed correctly through the structure that pays out monthly to Vanguard. Our theoretical $750 million bond pays a monthly portion of the 4% annual interest plus principal on a mortgage bond.

Just as an individual mortgage paid by a homeowner slowly amortizes – decreases in principal amount owed each month – so too does the servicer of the mortgage bond disburse a portion of underlying principal to Vanguard every month.

This means that 3 years from now our $750 million bond will have partly amortized, let’s say to 70% of its original face amount. Wall Street, if it trades this bond in the future, will still quote the original face amount, but mechanically only 0.7 of money will change hands at the time of a trade between Vanguard and its Wall Street broker. In other words If you want to buy $100 million of this bond – and it still trades at par – you’ll only need to pay $70 million to Vanguard for it, since it trades at a ‘factor’ of 0.7.

Each month the factor gets a little smaller, as each month more of the mortgage bond principal gets paid down. Toward the end of the life of a mortgage bond, you get to a sort of absurd factoring situation, in which only 10% of the bond face value is left, meaning a $1 million bond only has $100,000 principal left.

The mortgage servicer’s process is mostly automated, directing a precise amount toward the interest and principal, but the separation of the principal from the interest is essential.

If a homeowner pays off his mortgage early, or a foreclosure forces a sale of the home and repayment of a mortgage, that larger-than-expected payment shows up for Vanguard as a larger principal payment the next month. The mortgage servicer pre-pays a portion of the principal, reducing the bond factor faster than the original amortization schedule.

For the purposes of creating mortgage derivatives – the technology that makes mortgage lending even more efficient – the mortgage bond servicer separates the interest and principal amounts precisely before passing that on to bond holders. I’ll explain a bit more of that further down, after introducing the role of the mortgage insurer.

Mortgage Insurer

The mortgage insurer, in my example Fannie Mae, also earns a fee every month (a portion of that 0.375% to 0.5%) for guaranteeing loan defaults and loan losses within the portfolio. If a few of the 2,000 loans underlying the bond ‘go bad’ in any given month, Fannie Mae makes up the difference to bond holders owed a fixed amount, their 4% plus principal, every month.

Losses may occur because of delinquency – for example, some of the 2,000 homeowners stop paying on their mortgage for a few months. Fannie Mae makes up the temporary shortfall in funds, guaranteeing no diminishment of payment.

Losses may also occur because of foreclosure – some of the 2,000 homeowners lose their home. A special servicer will work to recover the proceeds of the foreclosure sale and apply that recovered money as an early payment of principal to Vanguard.

Under ordinary times, temporary losses from the 2,000 mortgages in non-payment remain relatively light. At any given time only a few homeowners are delinquent on their payments, and many of these resume payment as the homeowners stabilize their finances, or the house gets sold. In addition, bond holder losses due to foreclosure are typically not catastrophic, given that a 20% down-payment cushions bond holders from taking a loss, even when the house gets foreclosed upon.

Fannie Mae, and its close cousin Freddie Mac found this mortgage insurance business extremely profitable, for many years, leading up to the Crisis of 2008.

Under ordinary times, Fannie and Freddie were like insurance companies offering health insurance for 20-30 year-olds. Hardly anyone got sick. The occasional kid decided to ride a motorcycle and amassed huge fees after cracking his head open, but the majority of people never even saw a doctor. Fannie and Freddie collected fees for doing next to nothing.

Obviously, this comfortable arrangement all changed in 2008.

See upcoming posts on:

The Mortgage Insurance Crisis of 2008

and

An introduction to Mortgage Derivatives

Also, see previous posts on Mortgages:

Part I – I refinanced my mortgage and today I’m a Golden God

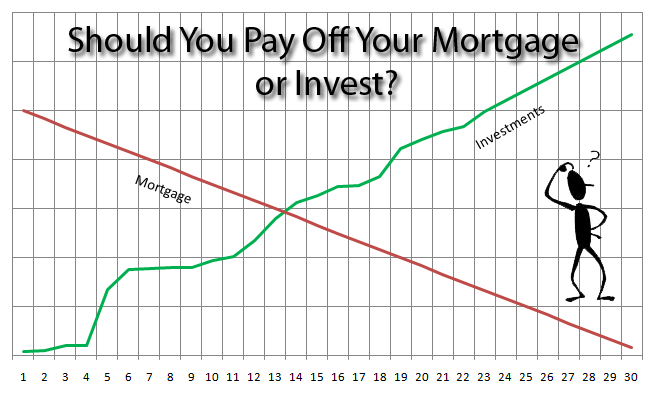

Part II – Should I pay my mortgage early?

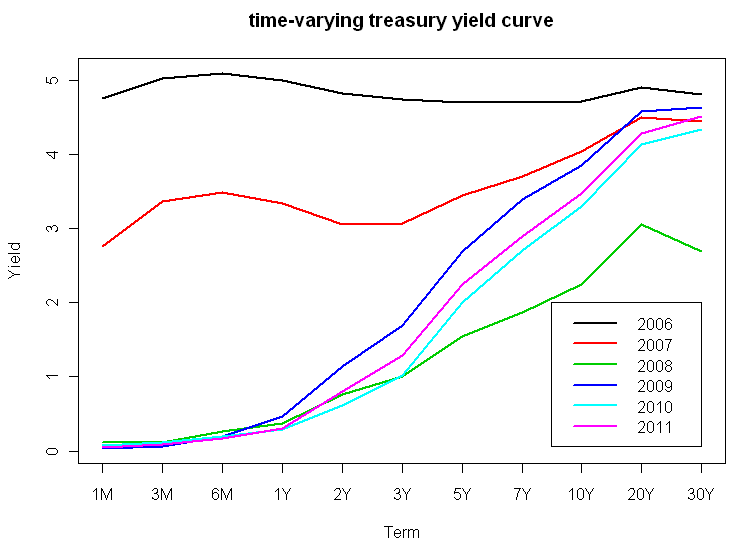

Part III – Why are 15-year mortgages cheaper than 30-year mortgages?

Part IV – What are Mortgage Points? Are they good, bad or indifferent?

Part V – Is mortgage debt ‘good debt’ A dangerous drug? Or Both?

[1] My managing editor (aka wife) points out that nobody outside of Wall Street or farmers knows what commodity futures are either, so my analogy is about as useful as a bicycle is to a fish. But since that is an analogy everyone remembers from that U2 song, at least we have some pop culture reference in here somewhere. Right then, so, we cool?

[2] Which, again, I can’t really explain if you still have no idea what I’m talking about. But remember the orange juice plot line in Trading Places? That was the futures market for another commodity, recently explained here. The price of the future bond fluctuates in anticipation of future supply and demand. Like the most active part of the mortgage bond market.

[3] “Conforming” is distinguished from “Jumbo” mortgages by size. In most cases the current conforming loan needs to be smaller than a set limit, currently somewhere between $417K and $625,500 depending on local real estate prices.

[4] All securities get assigned these registration numbers for tracking purposes.

Post read (9418) times.