Finance website Mint.com asked me some good questions for their blog. You can visit them there or enjoy the repost below.

As a former Wall Street insider, what do you think is the average person’s largest misconception about investing?

The average person thinks that what Wall Street does is so complex that it requires extremely bright specialists to handle the complex needs of individuals. And the average person thinks implicitly that complexity and special skills naturally justify high fees.

And while it is true that many to most people on Wall Street are bright and there are complex things happening there, all that intellect and complexity is irrelevant for the vast majority of individuals. For most Americans, including high net worth individuals, a very simple and inexpensive approach will serve them best.

If you had the ability to get every person in the United States to adhere to three financial principles, what would those be? Why?

Great question. More than principles, I would go with three financial attitudes. Those would be:

a) Optimism – You kind of have to trust that markets are going to work out fine in the long run, even when the short run and medium run look extremely frightening.

b) Skepticism – Most financial solutions you get pitched with constantly are irrelevant or overly costly.

c) Modesty – Be realistic and modest about your own ability to ‘beat the pros,’ and realistic and modest about the ability of professionals you hire to ‘beat the pros.’ Also, modesty about attributing one’s investment success can avoid mistakes due to excessive confidence.

How does life change when one has more financial literacy? What does it take to be financially literate? How illiterate are most people?

Financial literacy is a process that most people need to engage in, but a process for which there are too few guides. Most of our parents don’t know how to help. Certainly our teachers and professors are mostly unhelpful guides. Most of the ‘experts’ in the media are in fact salespeople in one form or another, so while they can tell you the positive features of what they sell, most are unhelpful in helping us sort out our different options in a suitably skeptical way.

Most well-educated people that I know are very uncertain what to do when it comes to financial decisions. Or worse, they have high certainty, but wrong ideas. Both versions of financial illiteracy can be very costly.

Financial literacy obtained in one’s early twenties, I think, would make the average, middle-class person $1 million richer at the end of their life. That’s the premise of my book. (More on that later, see below, the end of this post.)1

For higher earners, the benefits of financial literacy will be many multiples of that.

Investment is something that many people want to do, but don’t seem to fully take advantage of. What are some of the best practices one can employ to become better at investing?

The four biggest determinant of investment results are:

- Time (longer is better)

- Asset allocation (risky is better, and for non-experts/non-insiders, diversified is better)

- Costs (lower is better)

- Tax advantages (zero, low, or deferred taxes are better)

A powerful way to combine those four advantages – one that anyone can do but not enough of us do – would be to fund your (tax advantaged) retirement accounts (like an IRA or 401(k)), and purchase risky (100% equity) low-cost (probably index) mutual funds while still in your twenties.

A 22 year-old who does that for the next ten years is guaranteed wealth in his or her old age. In fact, it is impossible not to end up wealthy if a 22 year-old does that for ten years in a row.

If you’re not 22 right now, you won’t have as much time – which is a shame – but it’s probably still worth doing all the steps that I described above at any age.

The absence of 50 years of investment growth makes a wealthy old age still likely, but just less guaranteed.

Another important best practice is to employ automatic deduction as your main weapon to fund retirement and investment accounts. By that I mean you have to set up a system with your brokerage firm that automatically transfers money from your paycheck or your checking account every month (or every two weeks, or whatever) into your retirement and investment accounts.

The weird secret is that basically nobody has enough money left over at the end of the month or year for investing. But if we take that money out in small increments through automatic deductions, somehow we find we do have the money. This is one of those weird psychological tricks that make the difference between being wealthy or not being wealthy in our old age.

There seems to be a battle among many individuals who struggle with paying down debt and trying to save. What kind of advice can you give them?

If we have trouble paying down debt and saving, then we have to employ a series of Jedi mind tricks to get it done. Those Jedi mind tricks could involve three methods: a) automatic deduction b) budgeting, and c) radical transparency.

a) Automatic deduction, which I mentioned above, is probably the most powerful of these. You have to figure out a way to get your money out-of-sight, out-of-mind before you spend it. If you’re in debt, that means setting up automatic payments toward your high interest debt. If you’re trying to save or invest, that means setting up automatic payments out of your checking account and into a hard-to-reach savings vehicle or brokerage account.

b) Budgeting, which I hate to do – along with 99% of the rest of the planet – is not for me a long-term sustainable solution in itself. But over the short-term, it can actually help you alter your behavior when you start to write down every single freaking, nitpicky little transaction. The act of recording all transactions – even just for a couple of weeks or a month – I believe could change your behavior. That’s because you realize just how many non-essentials you purchase. It gets annoying writing down that packet of tic-tacs, and the latte, and the iTunes download, but then you realize you made $173.52 in non-essential purchases last month. And if you could dedicate the $173 extra to debt payments per month, you might actually be able to get rid your debt in this lifetime.

c) Radical transparency means announcing to your group of friends, or a single friend, or a debt-counseling group, your intention to get debt free in a set amount of time. Then you commit to regular (daily?) updates to your support person. The publically-stated intention, along with the support you will get from the group, may be the Jedi mind trick you need to actually kill your debt. There’s something powerful that AA members have figured out, which is that if you admit your powerlessness, and then you ask for help from an understanding group, you may be able to achieve the previously impossible-seeming task.

What do you think are some of the biggest challenges regarding debt (getting out of it, staying out of it, paying it off, etc)?

Debt exists in that psychological area of shame in which, like a cat with a broken leg, we want to hide our injury from others. We don’t want to admit our debts to others, and we don’t want to ask for help. We may even engage in self-destructive behavior – “Hey, let me buy this lunch for everyone!” – in order to hide our shame.

People stuck with excessive debt probably also have a fatalistic approach; they may believe that it’s not possible to reduce or manage their debt, so why even try? For people for whom this sounds familiar, I’d recommend a classic from the 1930s called The Richest Man in Babylon.

It may seem cheesy at first to the modern reader, but I think it effectively captures the psychology of a debtor’s resistance to getting out of debt. The book also has extremely practical steps toward becoming debt-free and then building wealth.

You say on your site that politicians are able to take advantage of citizens because those citizens are not as aware of financial matters as they should be. Please provide an example of this and how financial literacy can help fix this problem.

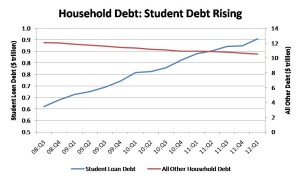

‘Taking advantage of’ is too strong a phrase. But I think citizens cannot properly police their officials if they don’t understand concepts like compound interest, which affects the future growth of government debt, public pension obligations, and Medicare and Social Security obligations.

Young people entering the professional world oftentimes come into adulthood with debt from student loans. What advice would you offer to these individuals?

The best situation would be to minimize student loan debt up front, but I suppose that line of thinking would get us talking about unlocked barn doors and horses that have already left the premises. It’s at least worth mentioning, however, that borrowing big sums of money to get a name-brand educational degree may not make as much financial sense as loading up on credits on the cheaper side (e.g. two years of community college, then transfer) before purchasing an expensive educational certificate.

Once you have a pile of student loan debt, I think the situation has to be tackled with optimism (student debt can be paid off) but realism (you may not be able to pursue your artist’s dream right now).

Stealing a page from the aforementioned The Richest Man in Babylon, I would suggest students do NOT forget to start an investment account. The author of that book has an interesting formula that, while it may not work for everyone, at least has the virtue of simplicity.

It goes like this:

1. Arrange your lifestyle such that you can live off of 70% of your take-home pay on a monthly basis. (I know, I know, this seems impossible. But still, it’s probably your only chance ever of making it all work out in the long run. Basically, yes, we’re talking about rice & beans, a subpar vehicle, and an apartment in a rougher neighborhood than you would prefer.)

2. Dedicate the next 20% of your take-home pay to paying off your debts.

3. Dedicate the final 10% of your take home pay to investments. In the beginning, this should to be channeled to an Individual IRA or 401(k).

When indebted, it seems like step #3 is an impossible kick-in-the-pants suggestion, because there’s no extra money to make this happen. The problem with skipping step #3, however, is that a student-loan-burdened individual will never get around to starting investing, until age 40. By then, it’s almost twenty years too late to get started.

So as impossible as it may seem, my advice for the student-loan-indebted recent graduate is to follow all three of the steps above. 70% for living expenses, 20% for debts, 10% for investments. Wash, rinse, repeat, every month. Rice and beans will suck for a while. But wealth will follow.

What are your thoughts on retirement and preparing for retirement? What about those who have already retired and are scared of outliving their money?

For people who are already putting away money in their tax-advantaged retirement accounts (IRAs and 401(k)s), the most important decision is probably their allocation to risky assets (like stocks) vs. non-risky assets (like bonds). The mistake most people make, in my opinion, is to dedicate too much money to the non-risky category.

This mistake is exacerbated by 98.75% of all investment advisors who tell their clients to invest in a mix of 60% stocks and 40% bonds. This piece of advice – which I strongly disagree with – serves the investment advisor well because you will not panic when the market crashes, and therefore you are less likely to fire your investment advisor for losing you money.

I think this advice serves the individual less well, since most people would end up far wealthier in the long run if they invested a higher percentage of their assets in the risky category.

My further thought process, which owes a heavy debt to the amazing book Simple Wealth, Inevitable Wealth by Nick Murray, goes like this:

a) Retirement accounts, by definition, are long-term investments. Even if you’re already retired, you need retirement money to last many years – often a few decades.

b) The longer your time horizon, the higher the probability that risky (like stocks) beats non-risky (like bonds).

c) Using the historical experience of the last 100 years, we can say the following: with a five-year horizon, stocks beat bonds 70% of the time. With a 10-year horizon, stocks beat bonds 80% of the time. With a 15-year horizon, stocks beat bonds 90% of the time. With a 20-year horizon, stocks beat bonds 99+% of the time.

d) Because most retirement money is invested for the longest time period, by allocating your retirement money to bonds you are basically saying that you believe that history is no guide at all, “it’s different this time,” and that odds-be-damned, you want to make a very low probability bet. That’s fine, and that’s what 98.75% of investment advisors tell you to do, but personally I think that’s a crying shame and a terrible choice, as well as a way to reduce your wealth in your retirement.

e) Although risky assets (like stocks) are extremely volatile in the short and medium run, a longer investment time horizon (plus automatic deduction dollar-cost averaging!) makes equity volatility less of a risk and more of an opportunity.

f) The real risk of investing your retirement money is actually with bonds, an allocation to which – for many people – will cause them to outlive their retirement funds. After taxes and inflation, bonds lose purchasing power. I understand this is contrary to conventional wisdom and contrary to what 98.75% of all investment advisors say, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Again, for a more articulate presentation of these ideas a) through f), I highly recommend Nick Murray’s Simple Wealth, Inevitable Wealth.

By the way, I’m not an investment advisor, so I suffer exactly zero consequences for people taking my advice on this topic or not. And that’s precisely why I have credibility on the issue. I’m not worried about being fired as somebody’s investment advisor when the market crashes.

And by the way, the market will definitely crash. I don’t know when, or by how much, but it will crash multiple times over the course of your investing lifetime. The key, however, is to not panic, and instead keep on doing what you were doing. Ideally, this means automatic deduction investing, so that you can dollar-cost average your stock investments at more advantageous prices when the market crashes.

Please share anything additional that you would like individuals to know about Bankers Anonymous.

I’m passionate about teaching finance. I’m on a mission!

My book The Financial Rules For New College Graduates: Invest Before Paying Off Debt And Other Tips Your Professors Didn’t Teach You is for the smart college graduate just starting out trying to navigate the highly consequential financial choices regarding car loans, debt, savings, home-ownership v. renting, insurance, entrepreneurship … even philanthropy and retirement planning.

Please see related posts:

Book Review: The Richest Man In Babylon, by George Clason

Book Review: Simple Wealth, Inevitable Wealth by Nick Murray

Book Review: The Automatic Millionaire by David Bach

Stocks vs. Bonds: The Probabilistic Answer

Post read (3241) times.

- When this post first came out in 2015 I hadn’t written my book, but I very much wanted to. The book came out in 2018, and if you liked this post you should, well, buy it! ↩