Podcast: Play in new window | Download

I had a conversation with a friend who ships trainloads of ‘frack-sand’ into the Eagle Ford shale in South Texas. We talked about the Natural Gas Revolution, as well as the surprising and possibly regretful turn his life has taken, far from working in book publishing in Brooklyn.

I had a conversation with a friend who ships trainloads of ‘frack-sand’ into the Eagle Ford shale in South Texas. We talked about the Natural Gas Revolution, as well as the surprising and possibly regretful turn his life has taken, far from working in book publishing in Brooklyn.

Bryant: Hello, my name is Bryant, and I presently work for a company that develops and operates frack-sand silo terminals in the Eagle Ford shale.

Horizontal fracking or hydraulic fracturing is a new technology. It’s been around probably — I would say since about 2007, but obviously now it’s really picking up. What it is, is instead of drilling and fracturing the earth, only in a vertical manner you drill vertical and horizontal and you fracture along the horizontal, through the shale.

Michael: When you and I were having a beer with a mutual friend of ours, he was describing basically oil and gas trapped in small little bubbles of rock that you can’t, with conventional drilling, get at. But you sort of smash it up with this horizontal drilling by shooting water and sand and chemicals, and it smashes up the rock and then the oil and gas flows. Is that basically still the right, accurate description?

Bryant: Yeah, that’s exactly right. First you drill it, and then — which means you just basically drill a hole and then you pull out all the drill pipe, and you go in with the fracking equipment. They call it the gun. The gun then blows off, which shoots shrapnel in all directions. After that, you pull that out. You then pump millions of pounds of water at a very high pressure, which then opens up the routes that the shrapnel first created to get to those pockets, and then you pump millions of pounds of frack sand, chemicals, and guar. It almost creates a slurry that helps keep those routes open so the oil and gas can actually flow out of the well.

Michael: To go back to the original description, your link in this chain is that you move huge amounts of sand from northern United States into South Texas?

Bryant: Yes, right now we’re averaging about 35,000 tons a month, which is about 70 million pounds so it’s quite a bit. It’s about 350 rail cars a month. Each one holds 200 thousand pounds.

Michael: 350 rail cars, so you basically take over an entire train, you fill it up with sand. It leaves Wisconsin, or where is this coming from?

Bryant: The mines are all located in the north, mainly Wisconsin, Minnesota. Apparently it has to be portions of the earth that were covered over during the Ice Age, and therefore have been untouched for a very long time, and the earth is very, very hard. This sand can basically deal with very high pressure.[1]

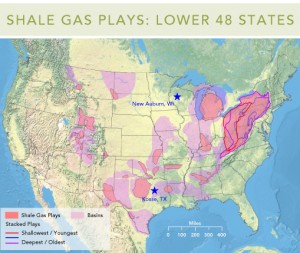

Michael: Referring to Eagle Ford. I know what it is because I live in South Texas, as do you, but basically this is a giant area covering a huge number of counties under which they’ve discovered there’s all this oil and gas trapped in previously undrillable area in the shale formation.

Bryant: The Eagle Ford Shale actually is a formation that spans from Laredo, obviously it continues into Mexico, I’m only giving you the American formation. Starts in the Laredo, Carrizo, Cotulla area, spans northeast right under San Antonio, up through Cuero and Kennedy, really very key spots. That’s actually where the first well was ever drilled, but that’s really the formation of it.[2]

What makes it the best play really in the world right now is the economics of the play. So, all the infrastructure is in place to bring in high volumes of sand, high volumes of water, high volumes of guar from India coming into the Port of Houston, Port of Corpus Christi. You’ve got chemicals; you’ve got bauxite coming in as another form of I guess sand or proppant from South America. So, you have infrastructure in for high volume of rail and barges, etc. There is a large amount of workforce. You have a lot of people looking to work. You have infrastructure, and then probably the most important is it doesn’t cost a lot of money to then get the product to refineries because you have all the refineries located on the Gulf Coast, so your margins to get it to market are a lot higher when you’re in the Eagle Ford. That’s really what makes it the most attractive play right now in the world.

Michael: I went down to Eagle Ford to tour it. I asked one of the guys down there; I said, “How long is this thing going to go for? How many years do we have for drilling?” He said, “What we’re looking at is probably fifteen more years of heavy drilling and fracking operations.” Is that what people talk about when you’re there?

Bryant: It fluctuates all the time. When this first started a couple years ago, you know, it was twenty to thirty years. Now they’re saying yeah, about fifteen. I read an article the other day it’s sixteen. That seems to be the consensus.

Michael: Then I asked him, “So if we’ve got natural gas reserves that are now available in the U.S. that we never thought were available because this stuff was trapped inside the rock, and now it’s being released from the rock, how long do we have great reserves of natural gas?” He said, “About ninety years-worth is of the known or probable, available natural gas.” Ninety years worth in the United States, does that sound right? Is that what people talk about?[3]

Bryant: I wouldn’t doubt it. The Marcellus Shale which encompasses a lot of up-state New York, Pennsylvania, even creeps its way into Ohio and down into West Virginia – the Marcellus Shale they say hasn’t even been fully, surveyed. They’re saying that shale alone if developed would become the largest gas shale in the world. So yeah, I believe that’s probably pretty accurate.

Michael: So if we’ve got ninety years — here’s where I go with that. When I think about what is going to be sources of energy for, say, the rest of my lifetime, your lifetime, pretty much what that tells me is that extraction of carbons from the earth is going to be cheap for the rest of our lives, and renewables that from a political standpoint I may prefer that we use solar power or wind power because it just seems cleaner and better for the earth, but that’s probably not going to be viable when compared to natural gas, for the rest of our lives.[4] This is sort of what I take away from it when somebody says yeah, we’ve got about ninety years worth of really cheap gas we can access. I don’t know if you have any thoughts about that.

Bryant: I do. I’m originally from the Northeast, so I work in an industry that is frowned upon by a lot of people in the northeast. So a lot of my friends will tell me, “Why are you involved in something when you could be involved in solar power or something greener?”

Michael: When I told the woman who looks after my kid a couple days a week that I’d been down to see a fracking site, she said, “Fracking, isn’t that illegal?” Do you get a hard time from people, from your old world about fracking itself?

Bryant: I do. I get a horrible time. I even hate myself sometimes. If you were to tell me ten years ago that I would have been doing business with Halliburton, I would have denied it, but I’m now in that world. I attend a lot of conferences where you look around and it’s just not the type of people I thought I’d be hanging out with all the time. Basically it’s all about fifty, sixty, or forty or fifty-year old white men that have just been raised in the oil field in some form. I like art and things like that. So it is a little crazy, and I do get a lot of flack from them, but I always do welcome a debate.

Michael: Do you have any thoughts you care to share about where you see yourself in five years, either how you’re going to make your fortune as an oil guy or not, and another would be whether you have any kind of personal regrets about starting out in the publishing industry and ending up as an oil guy.

Bryant: Yeah I think I’ll probably answer the second question first because it will lead to the first one. Obviously when you’re young and in college, you’re a real idealist. I was really into writing and reading and if I could do it all over again I probably would have focused my energies more on a lifestyle where I could have lived off of some kind of art or humanities. But life is not — I don’t think college really prepares you as well for reality, at least in my opinion.

Personally, I would have preferred to not have taken this route, but I’m not ashamed in what I work in. I do find it fascinating. It is something that moves on a global scale, which I think is very interesting.

In this business you’re constantly meeting people with money and with ideas and with connections. I hope to one day be able to capitalize on my knowledge and my connections, but I actually prefer to go somewhere else in the world. I wouldn’t mind getting involved in South America.

I think the way it’s going to happen in the rest of the world is actually a little more interesting because they’re going to have all the little problems that we’ve already solved here a long time ago. And problem solving is actually kind of a fun part of the job. The rest of the world really doesn’t have the infrastructure that we have here for moving equipment and materials. I think that would be even interesting to do. I don’t have to necessarily get involved in drilling or trading. It could be as simple as logistics. Things like that are actually — I think there’s room for it in the future, and hopefully five years from now I’ll have some options to do that.

Next up in Interview Part II – Bryant and I talk about the Eagle Ford labor market.

[2] And the Eagle Ford shale play has really changed the look of South Texas. It’s kind of a Mad Max Bizarro world down there.

[3] In other words, this Natural Gas Revolution is huge. As further described here.

[4] I talk about the implications of this in this posting here.

Post read (5919) times.