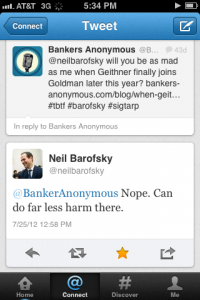

My favorite government watchdog of all time, SIGTARP[1], The Norse God of Financial Accountability, recently published another great critique of Treasury’s handling of TARP rules, this one about executive compensation within bailed out firms.

SIGTARP is a favorite of mine because they point out mistakes and errors with the TARP program. At its best, SIGTARP represents to me a hopeful sign that our federal government can learn from its mistakes.

In a time of deep cynicism about how “Washington is broken,” the Special Inspector General[2] role fills me with optimism. If our federal government is strong enough to weather pointed and non-partisan critiques from within, then we’ve got a pretty robust system.[3]

Which makes me happy. Ok, now back to the latest report.

Pay Czar blew it

SIGTARP reports that the Treasury department – and in particular the “Pay Czar”[4] put in place to limit executive compensation at bailed out firms – pretty much blew it.

Here’s what happened in simplest terms:

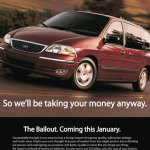

In 2009, Obama and then Treasury Secretary Geithner announced that firms that took TARP bailout money would be subject to rules about how much they could pay their top 25 executives.

This made and makes sense because

- When you take public money to save your firm, it’s a bit nasty to then turn around and send that public money out the door for private compensation in the form of salaries and bonuses. Which is EXACTLY what happened in 2008 with bailed out Wall Street firms, all of whom took TARP money, and then paid bonuses to their employees.

- At a time of deepening economic malaise, the ‘optics’ of bailed out executives taking big bonuses while Main Street folks lost their jobs and homes after earning 1/300th of the compensation seemed a bit, well, unfortunate.

- Geithner claimed that excessive executive compensation actually contributed to pre-crisis risk-taking. I don’t know if really buy this, but anyway, it was a theory of his that became part of the justification for limiting compensation.

- Restricting executive compensation should incentivize top executives to pay back their TARP money early, in order to return to the good old days of unrestricted compensation awards for themselves. Thus aligning taxpayer public interests with top executives’ private interests, as seems to have happened, according to Citigroup and Bank of America executives later interviewed by SIGTARP.

The Pay Czar rules said:

- The top 25 highest-paid executives at each firm should not receive cash compensation above $500K without special permission from the Pay Czar. Which permission, it turned out in retrospect, was not hard to get, as we read in the SIGTARP report.

- Compensation above $500K would have to come in the form of long-term restricted stock in the bailed company. Which is frankly not that onerous a rule, and probably ironically served to further enrich some executives who received huge stock awards at depressed 2009-2011 share prices. There’s a long and distinguished tradition of excessively compensating executes through share awards, as I’ve written about before.

- Compensation for the next 75 most highly-compensated employees had to be made in reference to average payments for comparable employees in similar jobs in the market. They couldn’t, or shouldn’t, be paid more than the average in the market without special permission. Which, again, makes sense because why are you being paid more than average when your freaking firm just got its ass bailed out with taxpayer money?

- These restrictions would stay in place until firms repaid their TARP bailout money.

My view on these rules, and what happened

When you look at these rules in aggregate, they do not seem to me restrictive at all. This is not written by some “Socialist Gubmint that wants to attack Capitalism and END OUR FREEDOMS.”

On the contrary, the only reasonable view of these rules, in my opinion, is that these rules were practically written by the bailed out firms themselves. Which, if you believe in at least the cognitive capture of the leaders of our regulatory system[5], you could plausibly argue they did write the rules.

Despite that, as SIGTARP reports, the Pay Czar totally failed to enforce even these executive-friendly rules, especially with some of the final TARP bailout companies, GM and Ally Financial.

The main points of the SIGTARP report, summarized for your reading pleasure (and to make your head explode with anger if you think about it too hard)

- General Motors (the pension-payments company that also happens to make cars that people don’t buy) and Ally Financial (formerly GM Acceptance Corp, the auto-finance branch of General Motors) were the last of a special group of extraordinary bailout firms[6] to pay back TARP money.

- Both firms’ executives made the case to the Pay Czar that restrictions on their executive compensation were counterproductive, because they were trying to be “competitive in the market” in order to pay back TARP money. The Pay Czar, according to SIGTARP, found this entirely self-serving argument persuasive when bending the compensation rules for GM and Ally.

- This happened, despite the fact that other TARP firms rushed to pay back TARP money, in order to loosen up their pay restrictions. In other words, the restrictions on executive compensation effectively accelerated repayment as intended for most bailed companies, but the Pay Czar later forgot this and felt like the rules should be bent in order to accelerate the repayment to taxpayers. The Pay Czar got this backwards.

- GM and Ally Financial in particular cost taxpayers quite a bit of money in the final accounting. Instead of collecting the repaid TARP money, the federal government sold its stakes in the companies to public markets at a loss – $11.159 B for GM, $1.763 for Ally. That didn’t stop the firms from getting the compensation rules bent repeatedly for them prior to these final accounting of losses.

- Both companies – as detailed in the SIGTARP report – managed to get pay raises, exceptions to the $500K limit, exceptions to long-term stock restrictions, and ignored policies and procedures put in place by Treasury regarding payment restrictions.

- Restrictions on executive compensation actually got looser and looser in the 2009 to 2014 period, even as expected losses at GM and Ally Financial became clearer and more likely.

- Treasury approved at least $1 million in pay for every top 25 employee at GM and Ally in 2013, despite the supposed rules in place to guide the Pay Czar, and prior to the ‘repayment’ of TARP through the government sale of shares to public markets.

In Conclusion

The 2008 crisis and aftermath makes different people mad for different reasons.

For me, the most egregious part of the whole episode has been the enjoyment of private profits with the benefit of public bailout funds before, during, and after 2008.

I love SIGTARP for making available the details on this egregiousness.

I’m mad, but I’m happy we have a paper trail to help me know exactly what I’m mad about.

Please see related posts:

In Praise of SIGTARP – Norse God of Financial Accountability

SIGTARP I – Truth in Government

SIGTARP II – Biggest Banks Still Too Big To Fail

SIGTARP III – The Citigroup Bailout

SIGTARP IV – What Small Banks Are Going Under Next?

SIGTARP V – My Front Row Seat to the AIG Debacle

[1] SIGTARP stands for the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program. Created by Congress, the SIGTARP periodically publishes reports on how TARP money was spent and misspent, investigations into criminal activity around TARP, and makes policy recommendations to Treasury about ways to do things better, or what it did wrong. I <3 SIGTARP.

[2] There are several Special Inspector Generals for a variety of important policy morasses in the federal government, including for “Iraq Reconstruction” and “Afghanistan Reconstruction. A big part of their role is to tell us exactly what got screwed up, how the money got wasted, And that’s a good thing.

[3] I mean, we can all get ‘mad at Washington.’ But the fact is that Russia and China are not robust enough systems to handle an internal critique like a Special Inspector General. They are too fragile and they know it. We are anti-fragile.

[4] The Pay Czar is actually technically known as the Office of the Special Master for TARP Executive Compensation, shortened to OSM in the SIGTARP report. I like the phrase Pay Czar better, however, so I’m going to stick with it for the rest of this post. The first Pay Czar was Kenneth Feinberg, previously in charge of the 9/11 Victims Compensation Fund, and later the BP Oil Spill Fund, and Boston Marathon Bomb Victims Fund. Feinberg was later succeeded by Patricia Geoghegan, about whom I know nothing.

[5] ‘Cognitive capture’ is shorthand for my favorite theory I learned from from Chrystia Freeland’s Plutocrats, which I reviewed earlier.

[6] The Treasury Department especially tracked the ‘exceptional’ TARP bailout money given to AIG, Citigroup, Bank of America, Chrysler, Chrysler Financial, GM, Ally Financial (formerly GMAC), because these seven firms were especially FUBAR in 2008, meaning the amounts were really high and the risk of taxpayer losses were also exceptionally high.

Post read (1187) times.

Ok, so it’s no secret I’m pretty sweet on

Ok, so it’s no secret I’m pretty sweet on