The most important rule for writing a business blog – at least my most inviolate rule – is to never, ever, forecast or make “market calls,” on individual stocks. I have broken this rule only once in my 5.5 years. It’s time to break my rule again. On the same damn stock.

I slather this self-rebellion in thick layers of irony. But irony with a purpose!

Some background. I last tucked my only-ever individual-stock forecast into a post in March 2015.

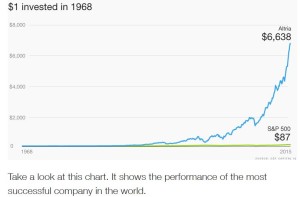

The point of that 2015 post was to highlight – in my contrarian way – the unpleasant fact that “sin-investing,” especially in a nasty tobacco company like Altria has been extraordinarily profitable over the past 40 years.

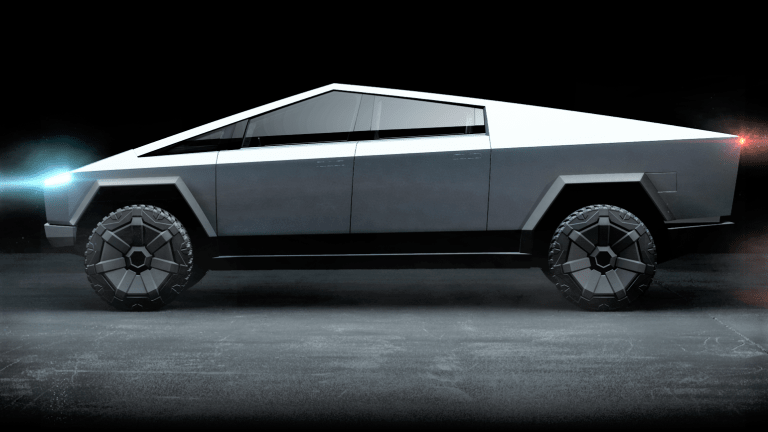

But that wasn’t my stock forecast. Instead, I contrasted MO with green-tech market darling Tesla the sexy electric-car company that combines virtue-signalling for reducing your carbon footprint with 0-to-60 acceleration in 1.9 seconds.

I wrote the following about Tesla in March 2015:

“Tesla Motors, to name one public company that I’m reasonably certain will be dead in five years, despite its $25 billion market cap, is an innovative company. But that doesn’t make it a good stock to own.” Then, to further metaphorically point to the bleacher seats while stepping into the batter’s box for my inevitable home run, I wrote “Would a few people mark their calendars for five years on Tesla and let me know how I did with my call? Because I AM SO RIGHT.”

Anyway, time flies. It’s five years later.

I’ll save you the hassle and let you know that Tesla stock is up 182% since then, from $200 per share at the time of my home-run call to $565 per share as I write this. The market cap has expanded from $25 billion to $102 billion. It’s up 35% just this year. Tesla will announce 4th quarter 2109 results on Wednesday January 29th.

Having broken my inviolate rule five years ago of never forecasting a stock in a column, it is only right and just that I have both my hypocrisy and terrible market call publicly mocked.

But that’s not the main lesson you should take away from this shameful episode. The main lesson is that you, too, should never forecast individual stocks. You will be emotionally invested in a way that hurts your chances of building wealth. You will buy, or sell, that stock too frequently. You will let fear and then greed cloud your judgment. You will look up that stock price exactly at the moment when you should be admiring your daughter’s ballet recital. (How many times do I have to tell you to put your phone down?) You will read headlines that confirm your preconceived biases and you will discount headlines that contradict them. You can guess how I know all of these accurate things about you.

Beyond the emotional reasons, you should avoid forecasting because you will also be wrong. You will even be wrong for all the right reasons. Like me.

Like, Tesla, by all rational analysis, has always been a stupid stock. It’s been overvalued forever. But as the Wall Street phrase goes, “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

I was correct about Tesla then, and I’m still even more correct, damnit! I will now double-down on all of my errors.

Unlike, say, software technology companies that enjoy infinite scalability, building an auto-manufacturer is highly expensive to scale. It takes cash. Tesla has burned billions in cash to build manufacturing plants in Nevada and Shanghai. The competition from other auto companies is intense and global. Regulation is massive. Innovation, for which Tesla is known, is expensive to implement. The company has nearly run out of money more than once in the past five years, even by the admission of their CEO/Evangelist Elon Musk.

And then there’s Musk himself. Ugh. As clearly brilliant and visionary as he is, he can’t stop himself from tweeting nonsense, earning rebukes and $40 million fines from the SEC, and lawsuits from fights he picks unnecessarily. He also employs his knack for distracting the media to change the subject, whenever they attempt to ask about Tesla’s lack of profit.

Oh yeah, and about that profit. Tesla has never turned an annual profit in nearly ten years as a public company.

Tesla’s market cap at $102 billion is larger than car companies Ford and General Motors combined. In fact, let’s compare those companies to Tesla. Ford sold 5.9 million vehicles in 2018, for a profit of $3.8 billion. General Motors sold 8.4 million vehicles in 2018, or a profit of $1.9 billion. Tesla, which has never turned an annual profit, sold 367,500 cars in 2019.

Tesla has sold 891 thousand vehicles in its entire history. Total. In other words, Ford and General Motors sell more cars in any given month than Tesla has ever sold. I could go on, but you get the idea. Tesla is a stock that mostly exists in our collective imaginations.

It turns out, Wall Street pros mostly agree with me about Tesla. It is the most “shorted” large stock on the US stock market, meaning sophisticated investors have bet against the share price, finding it as absurd as I do.

Shorting means hedge funds have sold shares at current prices in anticipation of buying back shares when they drop in the future. Shorting Tesla has been, as you can imagine, one of the most spectacularly unprofitable trades of the past few months.

Some people never learn. Like me and like you, the pros also shouldn’t be forecasting individual stocks.

Incidentally, I have no individual positions in any stock so nothing to disclose about conflicts of interest writing about Tesla. Index funds all the way, baby!

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Please see related post:

Sin Investing (and a mention of TSLA)

Post read (714) times.