Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Please click above to listen to full interview.

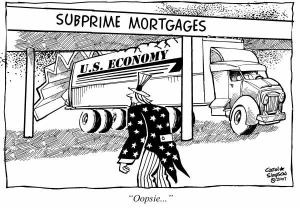

Mike sat down with David, a former mortgage originator during the boom times. They discuss the move into Subprime lending, the causes of the crisis, and shockingly, whether it was all worth it.

Mike sat down with David, a former mortgage originator during the boom times. They discuss the move into Subprime lending, the causes of the crisis, and shockingly, whether it was all worth it.

David: Hi my name is David and I used to be a mortgage underwriter and originator.

Mike: David, thanks very much for joining me. Can you give me a little bit of background to what is a mortgage underwriter and originator doing. What does that mean?

David: I started out originating. I was the one making phone calls. My initial contact was with the customer directly.

Mike: So, the customer comes in, and I think you said you started in the year 2000?

David: Yeah it was in 2000 and it was right before, or right I guess right at the start of the whole refinance boom. My territory was Northern and Middle California. So that’s kind of where everything starts.

As the Great Mortgage Crisis of 2008 slips into history, a consensus builds that the biggest breakdown of the system occurred because the different links in the mortgage production chain knew what they knew, and acted in their own self interest, but nobody knew enough of what the others knew.

I thought of this recently as I sat down with David. He worked as a mortgage originator precisely the same time I worked as a mortgage bond salesman. During that time, I never talked to a mortgage originator. Nobody I ever worked with on Wall Street ever sat down with the guys originating mortgages to compare notes. It never occurred to us. An economist might call this breakdown in communication ‘informational friction.’ You might call it ‘stupid.’

Cogs during the Mortgage Boom Times

Mike: So [from] 2000 to 2001, I’m interested in part because it parallels where I was. I joined the mortgage bond department in the end of 2001, which it sounds like you’d been at the job for a year. And what we were experiencing on the Wall Street side of things was an extraordinary boom in origination just the mortgage pipeline had never been bigger. Everybody essentially who owned a home already would benefit from refinancing. So everybody was refinancing at a breakneck pace. I’m assuming from where you were sitting that your business was booming, and you have something to offer that everybody wants, right?

David: That’s exactly what it was, and that’s part of the reason that I got the job of there, was I didn’t have any financial experience previous to that, I was a salesman as I had done for years and years before that. And a friend of mine that worked in the personnel department at the bank knew that, and knew that they were coming up on this huge boom of refinancing.

Since we were mainly dealing with A and A+ paper, the most qualified borrowers, there was never a situation where we had to sell things that they didn’t need. We just had an influx of people calling and an influx of business, and they needed people who could handle that. The department that I worked for grew exponentially over the two years that was there.

The phones were literally ringing off the hook, in the end of 2001, to refinance homes or to take home equity out because the rates were so good.

But back in those days, at least in the beginning, business was booming and everybody made money.

David: There was no risk involved at the time. If you got a borrower in from Northern California, from Carmel, who – say he made, you know, $3 million per year, and he’s got an 820 FICO, what do I care? He’s going to put 20% down, even if, for some reason, he falls off the face of the earth and he goes 6 months and he defaults, we get the house back into our portfolio because we paid for it, it’s our money. We sell the house again through our real estate side. Or through a realtor that we know, we make money on that, and we’ve got this 20% down, his $250,000 initially. There was absolutely no risk involved in lending to those types of borrowers.

Mike: There was just so much volume going through the system and everybody qualified essentially and everybody had home equity.

David: Yeah it was a flood. And our big territory was California, and that was like the beginning of like the tech boom. All the software guys were out there. And Google hadn’t even started yet, it was Yahoo and Microsoft and these guys were just collecting money and their bank accounts were huge and they really couldn’t account for all of it because they didn’t get normal paychecks or they got bonuses, or this and that, but they had perfect credit and they had a lot of money and we sold them houses.

Mike: So we know now, in the macro picture, 9/11 happens, the Fed lowers interest rates, there’s extraordinary amounts of money looking for some return, all the models say that mortgage are a great place to get a return, so on the investor side everybody wants mortgages, and on the retail side, everybody wants to refinance their house, which has gone up in value, so its just this awesome machine, and I was also a cog in the machine, in doing my bit. When you’re a cog in the machine it’s not always, it’s not obvious to us what this is all going to lead to.

The Move to Subprime and Alt-A Lending

And then two great new types of mortgage origination came along. Alt-A, which meant you could provide much less information than on a traditional mortgage application, and Subprime, which meant you could get a mortgage even though you did not have a history of actually paying your bills. We started to dive into that where I worked, and David’s two employers during that time period also entered the exciting new world of people with marginal credit and minimal screening of their applications. Again, so much money was being made.

I joined the Goldman mortgage desk in the end of 2001, beginning of 2002. and at that time Goldman had, pretty much that month, there was a guy named Kevin Gasvoda, he’s a Vice President and he’s got this mandate to get Goldman into this business because we’d realized that Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers were taking/stealing our market share in the mortgage department and we didn’t have a subprime or Alt-A program. And Goldman had basically not gotten into that business because of reputation risk, and we didn’t quite trust that these people would pay the money back, but suddenly in 2002 we were going to invest in that, and the models say that looking back over the last five years everybody does pay their subprime mortgages back. And Alt-A is a perfectly safe product if you structure it correctly, and by the way Lehman and Bear are making tons of money doing this, they are just printing money.

I distinctly remember this kind of back and forth from, internally at Goldman of ‘Should we be in this market?’

In the ‘90s they’d decided not to be, but by 2002, kind of just as I was joining, they were saying ‘We cannot NOT be in this market, we have to be there. We’ve not trusted it in the past but we’ve got to be there and it/s growing so fast. That’s my side of the subprime thing, so what’s going on, on your side, while that’s happening?

David: That’s pretty much, actually that’s exactly, almost exactly parallel to what was happening at my bank. It went from a kind of normal application process, so a normal application form, we’d call their bank for verification, they’d submit income, assets, they’d submit pay stubs that kind of thing, like you would nowadays if you went to get any mortgage, anybody.

Six or seven months into my stay there, so middle of 2001, we didn’t care anymore. I was literally getting applications with a social security number, a name, a job description, and a bank account statement, and that was it, and we’d write them a check for a million dollars. And that was happening all day long because it didn’t matter.

Six or seven months into my stay there, so middle of 2001, we didn’t care anymore. I was literally getting applications with a social security number, a name, a job description, and a bank account statement, and that was it, and we’d write them a check for a million dollars. And that was happening all day long because it didn’t matter.

Mike: The process of just social security number, job, that was for A-Paper, that’s high quality borrowers, that’s 2001

David: Those would be our no income, no asset borrowers,

In other words, Alt-A paper

David: they come in, we run their credit, and they’ve got an 820 FICO

Mike: Perfect credit, we’ll cut you the check

David: Yeah, we’ll give you what, it’s not a big deal.

David then moved over to USAA Bank, but did not enjoy the subprime market as much.

David: Um, I was there really briefy because I don’t, I didn’t think they were going in the direction that I wanted to go in, as far as that’s concerned…the jumped immediately into the, uh, mid-level and subprime lending because what’s they wanted to get into.

Mike: All the models said, sub-prime people actually paid back, if you looked the previous four years, they all refinanced and paid their money.

David: Absolutely all the math worked. But the thing is if you look back four years on anything it’s going to work. If you look eight years or ten years or sixteen years…you’d have to look as far back as the Great Depression – recently – to find where the curve was. It’s so big it’s hard to see the whole thing especially when you’re focusing on making money like everybody else was.

The reason I didn’t like it so much was they were gearing more toward sub-prime people, and I could obviously see they were starting to lend to borrowers who were not going to be able to pay stuff back.

I’m not saying anything about about USAA bank, obviously everybody was starting to do it at the same time. Because you’re right everybody said “They’re going to pay us back” even though we knew if you give somebody with a 40% debt ratio and you mitigate that by a credit score they still don’t have enough money to pay the loan back, no matter what their credit says and that credit might say that now I mean six months from now and eight months from now it’s going to drop 100 points because they just defaulted on the mortgage you sold them that was, that was out of their means. And that’s why I said I’m not gonna kind of do this anymore.

David moved back to a customer service job at a private mortgage broker, something he enjoyed immensely, in contrast to the previous work with Subprime and Alt-A borrowers.

The American Dream Business, Gone Bad

David: That was the opposite side of what I was doing before, where we were just handing out checks to people, you know, four or five years previous to that. And didn’t care about anybody or anything, just making money, this was helping people get into houses. And actually, like, making their dream come true. It’s not that trite a sentiment when you’re actually doing it. When you actually are able to call somebody and say we’ve got your loan approved, you’re going to get this house. It’s much more satisfying than just signing your name on a piece of paper that’s worth a million dollars.

Mike: So you, but you enjoyed that part of it?

David: Absolutely

Mike: It was satisfying to be originating and brokering mortgages for folks.

David: Yeah, and that’s kind of the, that was the fun part, was doing that, versus trying to sell products that probably weren’t suited for somebody to them, and thinking always in the back of your head, is this person going to lose their house, are we going to lose money, is everybody. Like, this is starting to kind of not, not be agreeable anymore.

David: Yeah, and that’s kind of the, that was the fun part, was doing that, versus trying to sell products that probably weren’t suited for somebody to them, and thinking always in the back of your head, is this person going to lose their house, are we going to lose money, is everybody. Like, this is starting to kind of not, not be agreeable anymore.

Small Mortgage Errors Compounded With Great Leverage

So, back to the economists, and the information frictions. One of the things I really liked talking to David about was bridging that information gap. What is it he knew, that Wall Street should have known. Its too late of course, but still, what if mortgage originators, mortgage bond salesmen, and mortgage investors had actually spoken to each other in the run up years to 2008?

Mike: With the benefit of hindsight lots of people have pointed out that all along the mortgage chain each person was doing their job more or less properly as they saw fit, and each person was acting in their own self interest and yet somehow there was information lost. Somewhere between either the models don’t take into account enough past information on the investor or bank structuring side, homeowners aren’t taking into account the idea that real estate values don’t always go up, they also go flat and they also go down. On the mortgage origination side lots and lots of banks went under because they sold wholesale packages to Wall Street, which then stopped taking them and putting them back and it just bankrupted the mortgage originators who couldn’t take back the, at that point, unsaleable mortgages.

So everybody got hurt, and yet it’s interesting because every one of us was trying to do the best we could. In the back of our minds “Huh, something’s not quite going right.” Do you have any anecdotes of having talked to homeowners about something being not quite right.

David: What I look back now and think about were all the times where we…we you stretch it a little bit. And if I’m stretching this person’s income by $1,000, or if they’re telling me they make you know $3,500/month, versus $3,200/month and I see their pay statements and it kind of makes sense and I’m just cursorily looking over it and signing off on it, well, that $300 has to come from somewhere, theoretically. That’s kind of what happened, and I’m that one person. And there’s one hundred of me. And there’s a thousand of my departments, and there’s a thousand of my banks. If you take all those little stretches and flubs and oversights that don’t mean anything at the time because you’re either caught up in writing a loan or making a deadline or a quota

Mike: Keep your volume up, make your monthly number.

David: Or even at the best, helping somebody get a house.

Mike: Right

David: All those things have to come from somewhere, that’s not just…they don’t just go away. So if you approve this person, or don’t approve this person, or you approve too many of these people, or a hundred of your compatriots are doing the same thing at exactly the same time then the numbers start to skew from the model to actuality and it’s like gaining weight or getting fat, you don’t notice it

Mike: it’s only a half pound per month, but a year later…you’re a lot fatter

David: Exactly, you don’t notice it until you’re 50 pounds overweight a year later, and then you start thinking about all the times you had an extra serving of ice cream, or you didn’t stop at, you know, two pieces of cheese, or whatever it is.

Mike: You’re making me feel guilty

David: Yeah, me too.

Mike: I like your explanation that the income has to be $3,500 [per month] but it’s actually $3,200 and there’s this missing $300/month, that where it’s close enough so we’ll just pass it on

David: Yeah

Mike: And yet, $300/month, you know, it gets put on the credit card and then eventually you’re talking about…

David: And that’s what it is

Mike: …You’re $20,000 in the hole and your house is in foreclosure.

David: It doesn’t seem like a lot to me. Because I’m thinking, “Yeah, no, this is fine.” Its only $20/month on their payments to give them this versus this, but 20 times a year, times thirty years, your asking this person to repay back thirty thousand dollars more than they are currently able to. And that’s assuming that their position is going to get better, instead of assuming their position is going to stay the same or get worse which is what actually happened.

Mike: It gets pretty geared up, pretty leveraged.

David: Yeah.

Mike: Small mistakes get amplified. On the Wall Street structuring side, where we knew to the Nth degree how to exactly satisfy the letter of the law with respect to how the rating agencies needed bonds to be structured – not the spirit of it, not we’re going to make some safe AAA-rated bonds and some A-rated bonds then BBB-rated bonds, but precisely the letter and not a single iota of wiggle room is you take those $300/month off income and then you gear that to the Nth degree of what the rating agencys will let Wall Street get away with.

All of the mortgage business was entirely a, what we would call a rating agency arbitrage, where you’re just doing precisely the thing that will get you the rating you need to sell it to your investors, but with the no wiggle room, and then as the origination is happening that way, even if you have a slight hiccup it’s all going to come down.

Was It All Worth It? David Says Yes

Towards the end of our conversation David and I were getting a little bit philosophical and then he surprised me, by saying the entire mortgage debacle might have been worth it. I had never met anyone who would say that outloud. But David did.

David: Yeah. That’s something I think about too. If it wouldn’t have worked out so well for everybody – yeah it went to something bad but – if that money wouldn’t have been made would everything still have kept rolling or would have just been kind of steady or stagnant. Let’s say you win the lottery, and you go out and you spend all your money in a year. Who’s to say that wasn’t the best year of your life? And it wasn’t worth spending all of that money on?

Mike: Were the gains in the lead up from say, 2000 to 2007, bigger than the ultimate loss of a steady-state of just steady growth?

David: and that’s coming from someone who isn’t rich, who isn’t wealthy. I didn’t make, you know, tremendous gains. I was just a regular employee. I made a good paycheck, a regular salary but it wasn’t, it wasn’t anything I could retire on. It wasn’t anything or it wasn’t going to have to work the rest of the, the rest of my life. So, just to be clear about who is actually saying this. It’s not someone who has, who has profited from that big wave, and I’m sitting on a big pile of money giving, giving an interview saying how good it was. This is someone who will has to work a job everyday for the rest of my life because the industry now probably couldn’t support what it did back then. And I still think that that might have been worth it to get where we are now to know what we know.

Mike: yeah it’s an interesting thing that most people are not saying, which is, the boom might’ve been worth the bust. Is that in a sense what you’re saying?

David: Yeah

Mike: both from a knowledge as well as from a wealth standpoint?

David: Yeah

Mike: That’s a really unusual statement.

David: It’s the position of someone who’s watched it from the inside and then the extreme outside. Someone who gas prices matter to, who knows what a gallon of milk costs. And, it still seems to me that the experience and that the situation is okay now, it’s not as dire I don’t think as people are making – it was – in like 2007 and 2008 when we almost actually literally lost everything.

Mike: we were staring at the financial abyss, living in caves

David: Yeah it was really close. It was a financial Holocaust. It was going to happen. Everybody was going to lose everything, at the same time. And banking was going to stop. But it didn’t. The fact is it didn’t, because we took everything that we had learned from the previous seven or eight years and said “Okay, this isn’t going to work. We’re seeing it not work.”

If that wouldn’t have happened, would we have even seen that. Would the curve have been shallower and longer, and had more detrimental effect, if the spike wouldn’t have been so great when it was.

Mike: I think that’s really interesting. Most people don’t have your philosophical approach to it. I don’t know either way.

David: As I said, it’s not to mitigate or to rationalize, you know, the millions of dollars that I made, because I haven’t. And it’s not positive just to be positive about it, to kind of negate others things or to ignore it. I’m by nature a very pragmatic person. But even that. You have to at least accept that the experience was worth it.

Post read (6615) times.

Alternatively, by law, you’re entitled to a free copy of your credit reports from all three credit bureaus once per year through AnnualCreditReports.com. But this only gives you the reports, and you’ll have to order your credit scores separately. Which is annoying. So skip it, and pay to get your score.

Alternatively, by law, you’re entitled to a free copy of your credit reports from all three credit bureaus once per year through AnnualCreditReports.com. But this only gives you the reports, and you’ll have to order your credit scores separately. Which is annoying. So skip it, and pay to get your score. Borrowing on a sub-prime mortgage will add 5 to 10 percentage points to the cost of your loan, or let’s say an initial $10,000 to $20,000 per year on even a small $200,000 mortgage. Just five years of that extra cost and you’re $50,000 to $100,000 poorer than you need to be. A better plan would be to settle all your outstanding debt problems in the next year. Later, with collections or tax liens in the rear-view mirror, the passage of time will heal your credit score. Waiting a year or two to build your FICO score up before buying the house will leave you wealthier in the long run.

Borrowing on a sub-prime mortgage will add 5 to 10 percentage points to the cost of your loan, or let’s say an initial $10,000 to $20,000 per year on even a small $200,000 mortgage. Just five years of that extra cost and you’re $50,000 to $100,000 poorer than you need to be. A better plan would be to settle all your outstanding debt problems in the next year. Later, with collections or tax liens in the rear-view mirror, the passage of time will heal your credit score. Waiting a year or two to build your FICO score up before buying the house will leave you wealthier in the long run. Since your income has been steady for a few years you should be able to get pre-approved. But expect that the lender, when it comes time to actually extend you a loan, will ask extremely invasive questions about your work and income . One to two years of federal tax returns will be the start of their inquiry. I can’t anticipate all of the ways a bank will try to vet your consistency of income, but be prepared to prove out anything you claimed as income.

Since your income has been steady for a few years you should be able to get pre-approved. But expect that the lender, when it comes time to actually extend you a loan, will ask extremely invasive questions about your work and income . One to two years of federal tax returns will be the start of their inquiry. I can’t anticipate all of the ways a bank will try to vet your consistency of income, but be prepared to prove out anything you claimed as income.