On February 1st, the City of Amarillo, TX broke ground on their brand new downtown $45.5 million publically-funded baseball stadium, the future 2019 home of the AA-level minor league Missions baseball team, a team currently based in San Antonio.

As I wrote about last week, I dislike these public-money stadium deals, for two reasons. First, the promised “economic development” too often is an illusory sales pitch that never comes true. Second, I get mad because sports teams owners should build their own doggone stadiums rather than depending on tricks with public dollars.

As I wrote about last week, I dislike these public-money stadium deals, for two reasons. First, the promised “economic development” too often is an illusory sales pitch that never comes true. Second, I get mad because sports teams owners should build their own doggone stadiums rather than depending on tricks with public dollars.

Despite my distaste, it’s useful to study these things to understand how they might come about. I describe that in the second half of this post.

As the Missions baseball team hits the road to “Amarillo by morning, straight up from San Antone,” in 2019, will we be getting a new publicly-funded stadium in San Antonio to keep pace with the panhandle? (Incidentally, if I don’t have you humming that George Strait cover song by the end of this post you deserve a full refund.)

I asked San Antonio mayor Ron Nirenberg whether he was aware of any negotiations with The Elmore Group to build them a nice new AAA minor league baseball stadium, in order to welcome the Colorado SkySox team slated to move to town in 2019. Nirenberg described the silence between the city and the Elmore Group as “crickets.” DG Elmore, owner of the Missions baseball team, replied to my query that “At this time, we do not have comments or information to share about a new ballpark.” About Amarillo’s stadium, Elmore replied “it will be ready opening day 2019.”

The combination of silence and “no comment” in San Antonio does not necessarily mean nothing is happening. City Councilman Robert Trevino, whose downtown District 1 was reportedly the destination target for a new baseball stadium as recently as last year, described meetings with the Elmore Sports Group at the National League of Cities summit in Charlotte in November 2017. The Elmore Group hosted at least 5 San Antonio City Council members including Trevino, for a tour of Charlotte’s downtown minor league baseball stadium, presumably to warm them up to the opportunity in San Antonio. Trevino, a professional architect, said urban design considerations around a baseball stadium weigh heavily with him. He says his support for a future stadium would depend on whether existing downtown development plans already in place and elements such as parking and transportation coordinate well with a new stadium.

That coordination, necessary to achieve economic development, is often lacking, according to Heywood Sanders, professor of Public Administration at UT San Antonio. Sanders points to Houston’s Toyota Center – home of the NBA Rockets, as a relatively successful development on Houston’s east side of downtown.

That coordination, necessary to achieve economic development, is often lacking, according to Heywood Sanders, professor of Public Administration at UT San Antonio. Sanders points to Houston’s Toyota Center – home of the NBA Rockets, as a relatively successful development on Houston’s east side of downtown.

“The city and business interests (of Houston) wanted to develop downtown. The decision was a very conscious and well thought out one,” says Sanders.

Sanders contrasts that with the San Antonio experience. “If you’re going to do it, how do you do it? Do you plan surrounding development in a coherent, well thought-out way, or do you just plop the structure down and cross your fingers?” Sanders asks rhetorically. “If ever there was an example of the latter, there are two examples in San Antonio. First, the Alamodome, and then subsequently the AT&T Center.” Those have failed to spur surrounding development, to say the least.

So I’m nervous about any promised economic development based on past history. But also, financially, what can we learn from Amarillo’s public stadium deal?

One interesting element, at least to me, is the way the $45.5 million deal patched together money from sources designed to avoid political backlash. I’ll describe those in detail as they’re clearly from a playbook that sports owners and political leaders use over and over again.

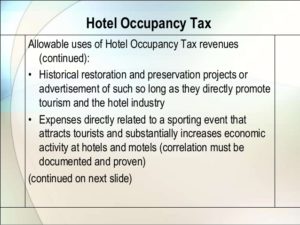

The biggest source of funds for the stadium will be a hotel occupancy tax (or “HOT” for those of you who like cool acronyms.) The HOT gets collected as a sales tax on hotel rooms booked in Amarillo. Voters narrowly approved $32 million to be used for constructing a stadium in 2016.

The HOT allows officials to say, with a straight face, that mostly non-residents – hotel visitors to Amarillo and hotel owners – pay the taxes for financing this stadium over the long run. You can probably see the political advantage of using the HOT.

The second most important source of funding for the stadium is already-collected HOT money that will be dedicated to the stadium project. Also importantly, HOT funds are specifically intended to be spent on projects to spur Amarillo’s downtown and tourism business. That’s the purpose of the HOT. Knowing all that, you might reasonably say, and many will say, that the public financing of Amarillo’s stadium is using money already set aside for this type of project and doesn’t burden residents with any new taxes.

The second most important source of funding for the stadium is already-collected HOT money that will be dedicated to the stadium project. Also importantly, HOT funds are specifically intended to be spent on projects to spur Amarillo’s downtown and tourism business. That’s the purpose of the HOT. Knowing all that, you might reasonably say, and many will say, that the public financing of Amarillo’s stadium is using money already set aside for this type of project and doesn’t burden residents with any new taxes.

A third source of funding will be a tax only levied on downtown commercial real estate owners.

If you were a grumpy cynic like me, however, you might think the following two things: first, the creation of a HOT is the original sin. Once you vote for a tax dedicated to downtown public development projects, you inevitably end up with things like stadium deals and downtown convention centers, whether they make long-term sense or not.

“Well, heck, we have the money already!” is a logical thought process of civic leaders, and the first step towards a badly thought-out plan.

Second, a better version of a HOT – in my imaginary ideal world – would create less restricted uses for the funds. Instead of building stadiums for privately-owned sports teams, my ideal civic leaders would use HOT money to fund other things like parks or libraries or complete streets or any number of projects that don’t direct public money toward hosting a private company’s business.

The finance term for this idea is that “money is fungible.” In other words, if you’ve got $10 million in saved up funds, or $32 million in future tax revenue, is a stadium really the best public use of public funds? Obviously hotel owners don’t support city governments that set up a HOT without restrictions to benefit them. But in my imaginary ideal world, local governments don’t only do what hotel owners, and sports team owners, want.

Please see related posts:

Post read (159) times.