Ready for another crazy, but great, money idea that could change your life for the better?

Salary transparency. At your workplace. Meaning: everyone knows what everyone else gets paid, every year. No, wait, stick with me here. I know you suddenly felt a little ill. But salary transparency works to your advantage.

Salary transparency is an idea most commonly discussed as an ideal in recent years among Silicon Valley tech companies, but it shouldn’t begin or end there.

San Antonio-based software engineer Nancy Hawa of DevResults a data-organization and data-visualization company based in Washington DC, pushed for salary transparency in her 12-person company earlier this year. DevResults decided to take the plunge.

As a result, her CEO and COO released to employees a completely open set of data around not only what all employees make this year, but the entire history of everyone’s compensation.

The initial feeling among Hawa and her colleagues with that disclosure, she admits, was dismay. She described the higher-paid employees in the office holding their heads at their desks in a kind of awkward embarrassment. Lower-paid employees, like Hawa, held their breath to find out what would happen next.

To the credit of DevResults’ leadership, they announced that despite what appeared to be “unfair pay” then, nobody would be paid less as a result. Over time, Hawa reports, lower-paid employees received a bump up in pay to put them in line with their colleagues. Transparency for Hawa meant she will be paid a lot more, not only this year, but in the future.

I learned from my conversation with Hawa a bunch of the nuances around salary transparency, a topic about which she is passionate.

The first nuance is about the “Why?” of salary disclosure.

The two best reasons to want financial transparency are to fight corruption and to ensure fairness.

I wrote earlier about income tax transparency, which is mostly about fighting corruption, and somewhat less about fairness.

Salary transparency is an even more radical departure from current norms than tax transparency. I’m increasingly convinced good business leaders should institute it as a matter of setting company culture.

Now, before you all freak out, salary transparency actually is somewhat normal in certain circumstances. As Hawa notes, “The State of Texas is not a progressive or radical organization, but they decided they needed salary transparency.”

Texas believes strongly in salary transparency as a public policy value, presumably for both anti-corruption and fairness reasons. I did an experiment, moments ago, to answer the question of how long it would take me to figure out Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s annual salary. The answer, in my case: 46 seconds. He makes $153,750 per year.

But immediately, I realized the next important nuance about transparency.

Partial Transparency

One of Hawa’s main warnings is that ‘partial’ salary transparency is actually destructive. With ‘partial’ disclosure she points out, you move quickly from no salary information to salary misinformation.

For example, an online search would tell you that Texas legislators earn $7,200 per year. But that number totally overlooks the generous pensions they can accrue over years of service, as I wrote about earlier in the year. So ‘salary transparency’ can be done well, but it can also be done badly.

It took me 41 seconds to find that my wife has part of her salary disclosed online as well, as she is paid part-time by a State of Texas entity. That partial disclosure, however, is misleading because it’s only part of the story. Again, partial disclosure can obscure rather than illuminate.

Hawa also cited companies that release “salary bands” rather than all salary data. All that does is potentially hide big differences in total compensation within wide ranges, like $40,000 differences, as she has observed elsewhere. Also, releasing general information about characteristics of employees, like “new hires receive $X in salary, but with some exceptions” can actually deceive.

Why the exceptions? And why the non-identifiable descriptions? Selective disclosure, Hawa argues, is often worse than no disclosure at all, because it misleads.

I wondered if only a relatively “flat” organization would want to radical transparency. Hawa doesn’t think so. Companies should be free to pay for star performance, as long as management can justify it.

“The company doesn’t have to aspire to flatness, but does have to aspire to fairness,” says Hawa. “Unequal is not the same as inequitable.” Those seem to me important points as well. Pay as much as you want or need to, as long as you wouldn’t be embarrassed by everyone knowing everyone’s pay.

If you’re a business owner who would be embarrassed by full salary transparency at your firm, what does that say about your method of paying folks? In an important sense, Hawa believes, the discomfort is the point. Hawa described her colleagues’ initial discomfort as a positive rather than a negative.

From Hawa’s perspective, transparency challenges leadership to be introspective. That’s where the hard conversations, and maybe some learning, can begin.

Says Hawa, “If you are leader, give yourself the opportunity to be challenged by your employees. If your salaries are fair, you’re good. If they are not, you [the manager/owner] have something to learn.”

Who Benefits from Opacity?

I’m pretty interested in the thought experiment. This all got me thinking about the fact that salary transparency is really not considered ‘normal’ in most workplaces. But why? Why are we unwilling to be transparent? What are we uncomfortable with? Who benefits from the secrecy?

For competitive reasons, we can all agree it makes sense not to publish your data to your competitors. But to ensure fairness within your own organization, wouldn’t full disclosure for current employees reduce mistrust?

I asked Hawa if she thought disclosure helped managers run her business better.

“I think there’s a business value in taking this off of people’s minds.”

And if you are a worker at an organization and the idea of salary transparency makes you uncomfortable, you should probably realize that secrecy isn’t your friend. You might have some initial shock and resentment upon disclosure, sure, but after that you would likely benefit. Secrecy is a tool in the hands of management.

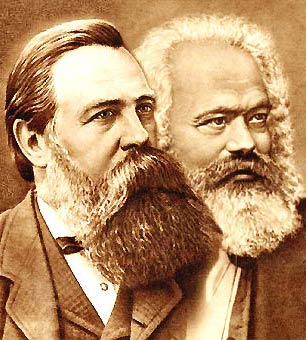

I think if you’re a worker worried about salary disclosure, you should remember the words written by a couple of German guys who became famous in 1848: All you have to lose are your chains!

A version of this post previously ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

City Economic Development Transparency – SA and Houston failing grades

San Antonio and Houston need transparency taken to 11

TX Legislative Salary transparency and opaqueness

Post read (246) times.