Editor’s Note: A version of this story ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle on September 17 2023. Since this is an ongoing (and soon to be updated story) I figured Part 1, although a few months late, needed to be posted here.

Following the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th largest bank failures in US history – that all occurred in Spring 2023 – a natural question is: What happens next?

I’ve never thought it likely that only failed banks First Republic, Silicon Valley, and Signature made major errors last year when the Fed aggressively hiked rates, while the other 4,697 banks in the country did not. Only one other tiny bank in Kansas has failed since then. It’s the dog that, eerily, hasn’t barked in the night.

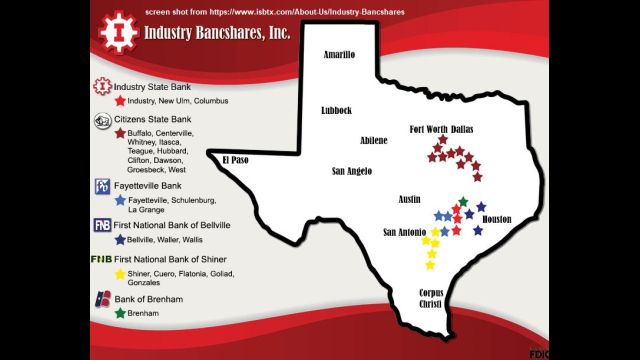

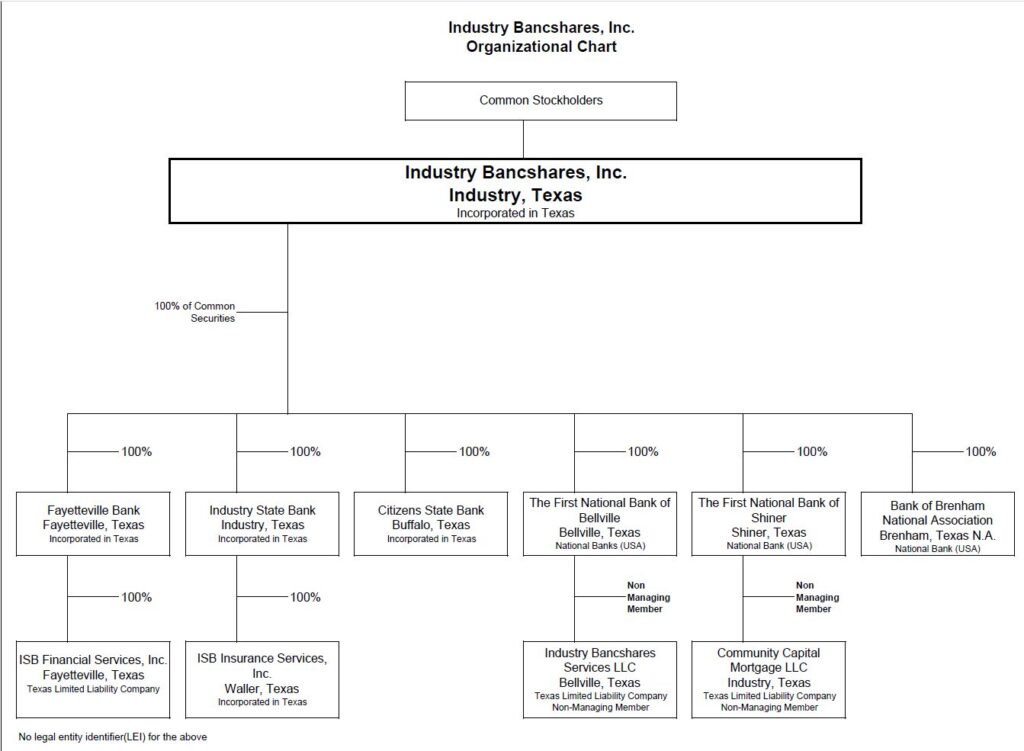

Industry Bancshares Inc, has 6 subsidiary banks and 27 branches just a few hours’ drive from each other in the rural counties between the Texas triangle formed by Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio.

The six subsidiary banks of Industry Bancshares, Inc are Citizens State Bank of Buffalo, TX, Bank of Brenham NA, Fayetteville Bank, First National Bank of Bellville, First National Bank of Shiner, and Industry State Bank of Industry TX.

Since at least December 2022, and including through their latest public filing of financial data in June 2023, all six of the banks that together make up Industry Bancshares has reported a significant negative net worth, using traditional accounting standards.

Bank Solvency

I don’t mean to be alarmist. Like shouting “fire” in a crowded theater, shouting “insolvent!” in a crowded bank lobby is neither kind nor prudent. Hopefully you watched the movies “Mary Poppins” and “It’s a Wonderful Life” so you have an intuitive sense for the fragility of all banks, especially to the extent that the FDIC only guarantees deposits up to a certain point.

The people who should be alerted to the financial stats I’m citing, however, are the 3,216 depositors at these 6 banks who have a reported $2.2 billion in accounts over the $250 thousand FDIC guaranteed limit, as of June 2023. This post is aimed specifically at those folks with billions of dollars in under-insured deposit accounts. Shareholders and board members of course should stay alert as well.

A spokesperson for Industry Bancshares Inc responded to a series of my questions, “Industry Bancshares, Inc. and our six chartered banks have capital levels that significantly exceed the required regulatory minimums, are financially strong and well positioned in the current environment to continue to serve our customers throughout the communities we operate in Texas.”

Not credit mistakes, but interest rate mistakes

Unlike past banking crises, the banking crisis of 2023 is not about losses in credit portfolios, meaning loans banks made to businesses or real estate that went sour. Industry Bancshares in fact has a pristine loan portfolio, with each subsidiary reporting less than 0.25 percent of non-performing assets at the end of 2022. This is very clean.

Instead, banks are showing losses on their bond portfolios. Most banks hold lots of bonds, and most bonds lost money in 2022, when interest rates went up quickly. So most banks have losses to report this past year on their bond portfolios. Banks publicly report, every quarter, how much they’ve lost (or gained) on bonds that they hold.

Says the bank’s spokesperson, “Over the past 30 years, our bond portfolio strategy has enabled us to maintain strong earnings and bolster our capital position. The bond portfolio is comprised of high-quality, performing investments such as U.S. government treasuries and agencies and highly rated Texas municipal securities. The current unrealized losses in our bond portfolio are just that – unrealized. Our high credit quality, highly rated bonds continue to perform as agreed.”

The bank declined to respond to my question about what changes if any have occurred in the bond portfolio, or the value of the portfolio, or hedging strategy, or interest rate posture since the bank last publicly reported numbers on June 30, 2023.

An outlier in AOCI

The losses that banks have on many of their bonds classified as “available for sale” are reported as an accounting line item called “Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income” (AOCI). In plain language this means “how much are our bonds worth today, if we were forced to sell them, compared to when we bought them?” If they are worth less today, then AOCI is a negative number.

Two other important accounting line items matter to this story, before I explain how much of an outlier Industry Bancshares is among US banks.

First, banks calculate and report their net worth in two different ways. One is called “Total Equity Capital” and is calculated according to regular business accounting standards (aka generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP.) You could think of this as the difference between what they own, and what they owe. Standard stuff for how we would calculate the net worth of any business.

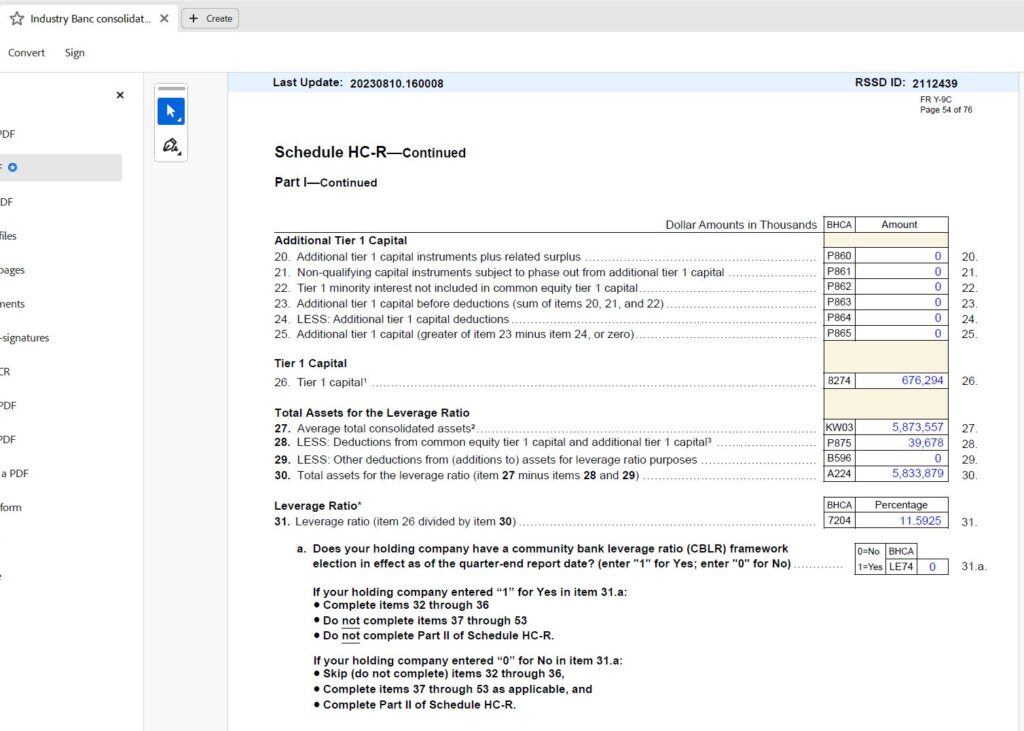

A different calculation is called “Common Equity Tier 1 Capital” (aka CET1) which follows specific bank regulatory rules, and it basically allows banks (and their regulators) to more or less ignore bond portfolio losses, in most cases. When a regulator looks at CET1 instead of GAAP results, a bank will look fine, even as it reports extraordinarily negative AOCI numbers.

Here’s where Industrial Bancshares’ quarterly reports from June 2023 are very interesting. (What I mean is now is the point to unglaze your eyes from my accounting lesson, and sit up straight in your chair.)

Industry Bancshares’ Unusual Situation

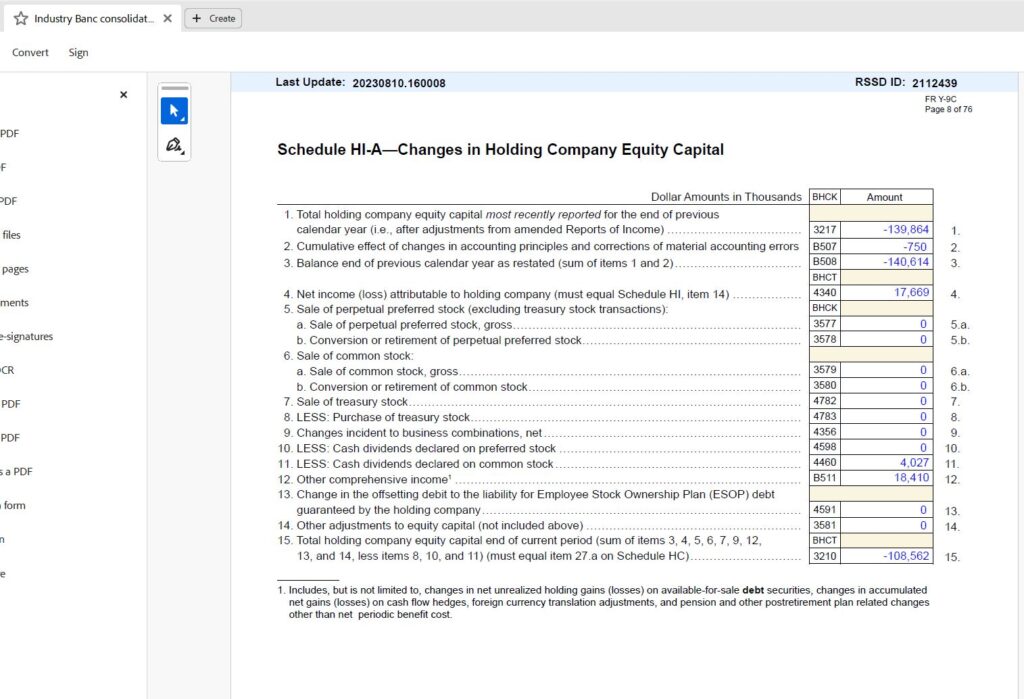

Using data from official bank accounting reports, just a mere 15 banks in the entire country had a negative “Total Equity Capital” number at the end of June 2023. Interestingly, the top 5 worst banks on the list, or in other words the banks with the lowest net worth on the list of 4,697 banks in the country are actually part of the same bank holding company. Number 7 on this ignominious list is also part of the same holding company. Yes, you guessed it, they are the 6 banking subsidiaries of Industry Bancshares Inc of Texas. All 6 subsidiaries have a negative net worth, and as a result so does the consolidated bank holding company. All-in, Industry Bancshares is currently supporting $5.8 billion in assets but has a combined “Total Equity Capital” of negative $128 million, as of its June 2023 report, or $108 million at the holding company level.

In the plainest language, what does negative total equity capital mean? It’s not just an accounting problem. If depositors and lenders to the bank all wanted their money back tomorrow, and if the bank managed to sell all of their assets (including their bonds) to give that money back, negative equity simply means there wouldn’t be enough money. In simplest terms, they’d be short $128 million. At current prices, their bonds lost so much value last year that there isn’t enough to cover depositors and lenders to the banks. And the bonds didn’t recover enough in the six months from December 2022 to June 2023. They reported negative $159.7 million total equity capital in December 2022.

The fact that there are only 15 banks out of 4,697 in the country with a negative net worth, but 6 of those banks are actually the same bank holding company, makes Industry Bancshares a strong outlier on this measure, according to publicly reported data in June 2023.

And look, I’m not your licensed financial advisor, and your mileage may vary, but personally I like to bank with an institution that has a positive net worth. Actually I’d be fine because, sadly for me, I don’t have balances over $250 thousand at my bank, but you know what I mean.

In response to my query about their $2.2 billion in 3,216 underinsured deposit accounts as of June 2023, the spokesperson for the bank replied “We have a growing, diverse, stable, and loyal deposit base. Our team of bankers use their experience and industry best practices to counsel our customers on how to safeguard their large cash balances…With six chartered banks we can increase FDIC insurance for customers across our affiliates. In addition, we utilize IntraFi Network, a solution that helps bank depositors access FDIC insurance above $250 thousand, to ensure our customers have access to FDIC insurance coverage.”

Another independent ranking

Bauer Financial, a bank rating group, assigns ratings every quarter to banks based on their financial strength.

In their June 2023 ranking, five out of 487 of banks in Texas merited 2 out of 5 stars, indicating a rating of “problematic.” Twenty-three banks out of 487 got 3 stars, indicating “fair” financial health. All 6 subsidiary banks of Industry Bancshares received 3 out 5 stars in June 2023. That’s a rating on par with San Antonio-based insurance and banking giant USAA. Although Bauer is indicating some cause for concern, they are not highlighting Industry Bancshares as an outlier the way the AOCI measurement I cited does.

So why haven’t regulators shut them down?

So if these banks are such outliers, when considering their bond portfolio losses and their overall business value, and this information is known and public, why do regulators allow them to be in business?

I mean, one would assume and hope regulators are paying attention. The Dallas Federal Reserve would have responsibility for the bank holding company. In response to my query, the Texas Department of Banking replied formulaically that they could not comment, among other things, on “information related to a regulated entity’s financial condition or business affairs.”

So I’ll speculate instead. The answer is likely a combination of:

1. A bank accounting technicality,

2. A purposefully gentle treatment of bond portfolio losses by regulators, and

3. Depositors over $250 thousand being blissfully unaware of the risks they currently run.

The bank accounting technicality issue is that regulators essentially have turned a blind eye to AOCI losses, and instead use the special banking health measure – CET1 – that ignores it. The thought process I guess is that as long as banks don’t have to sell their bonds at current market prices, they do not have to lock in their losses. And if depositors don’t flee, and the bank doesn’t sell the bonds at a loss, and other problems don’t crop up like credit losses, everything is fine in the long run.

The regulatory treatment of CET1, which ignores bond losses, allows the spokesperson for the bank to truthfully say in response to my query: “We have increased our Tier 1 leverage capital levels in each of the last 15 years, and in 2023 those levels have continued to increase. As of July 31, 2023, Industry Bancshares, Inc.’s Tier 1 leverage capital is 11.7% and total risk-based capital is 29.7%, which is in the 99th percentile of our peer group and is well above the regulatory definitions of well capitalized.” The bank, like regulators, focuses on CET1.

In fact a special program called the Bank Term Funding Program was created in March 2023 in the wake of the Silicon Valley and Signature failures – failures due to their bond portfolio losses and subsequently depositors fleeing! – to save banks from having to abruptly sell their bonds if they started to lose depositors or needed liquidity for any other reason. It’s a program put in place on an emergency basis that shields banks from the consequences of their losses on their bonds. In plain language, under this program, banks can borrow from the Fed against their bonds in amounts just as if they haven’t had any losses. In the banking world there’s a concept called “extend and pretend” that banks sometimes offer to their borrowing customers who have trouble paying back their debts. This program is a bit like the Federal Reserve offering “extend and pretend,” but for banks with bond portfolio losses.

The positive case for Industry Bancshares

What could a bank like Industry Bancshares, Inc and its subsidiaries do in this scenario to improve their lot and protect their uninsured depositors? The prudent short-run solution is to either merge with a stronger bank or sell to a stronger bank. Were I the acquiring bank, I would look very closely at the negative net worth and bid accordingly. Acquiring banks understand bank accounting very well.

Another short-term fix is to raise more capital from investors, which can then be used as a cushion against losses or fleeing deposits. Industry Bancshares last raised equity capital in 2017, according to SEC filings. Were I a current or prospective investor, I’d want to know their current position, but maybe they already do? The bank declined to respond to my question of whether it had sought to raise additional capital to bolster its negative net worth.

Were I an uninsured depositor with a commitment to sticking with one of these banks, additional capital would be the main thing I’d demand. The bank did not to respond to my question of whether the bank had paid investors dividends in 2022 or 2023. Documents I reviewed showed the bank did pay dividends to investors at least from 2014 to 2019.

The long-term fix, or no fix at all, is to wait. Given enough time, a successful bank franchise can earn money and climb its way out of a financial hole. Not counting their bond losses, the combined banks earned $76 million in 2022. At this pace of earnings, and assuming no change in their bond portfolio, they could climb back to a roughly breakeven, a zero net worth, in about two years.

Their bond portfolio may recover in time. As long as depositors do not flee and regulators give them time, these banks may eventually survive and thrive. But for anyone with more than $250 thousand in your account, you’ve been warned.

Please see related posts:

USAA Bank reports 2022 results – Not Great

Post read (3199) times.