You think we have some difficult divisions within our country? Have you noticed what’s happening lately in Greece?

You think we have some difficult divisions within our country? Have you noticed what’s happening lately in Greece?

I write this from my family’s summer vacation. My wife, my daughters, my mother and I have immersed ourselves in sunny beaches, folkloric cobblestone streets in a two thousand year-old village, and chocolate croissants eaten on the daily. We are blissfully happy on our Greek island paradise, thank you for asking.

But! As an amateur dabbler in the dismal science – economics – I can’t resist pondering the underlying finances and of the beautiful place I’m visiting.

Ugh. I am sorry I lifted up that heavy rock, to see what blackened worms lay squirming beneath.

Worms like the unemployment. The inability to control their own destiny. The maybe inevitable reaction to this horrific situation: a radical left-wing party in power clashing with Neo-nazis in Parliament.

Worms like the unemployment. The inability to control their own destiny. The maybe inevitable reaction to this horrific situation: a radical left-wing party in power clashing with Neo-nazis in Parliament.

Greek unemployment stood officially at 21.5 percent at the end of 2017, an improvement – if you can really call it that – from rates of 27.5, 26.5, 24.9, and 23.5 percent respectively the previous 4 years, 2013 to 2016.

How does that level of unemployment feel to the Greek people? Can you picture those grim black and white photographs of the Great Depression?

Compare those numbers to employment in the US during the worst stretch of the Great Depression, 1932 to 1936: 23.6, 24.9, 21.7, 20.1, and 16.9 percent respectively.

The Greek rates of unemployment over the past five years are similar, but actually a bit worse, than the US rates of unemployment in our darkest days. Think breadlines and grinding poverty in the cities and dust bowls in the agricultural areas. Your parents and grandparents were forever changed by those years.

And there’s not necessarily a cure for the Greek unemployment situation.

Mainstream economists believe that the best monetary policy response to high unemployment – meaning what a central bank should do with the supply of money – is to vastly increase the amount of money circulating in the economy.

During the financial crisis in 2008 in the US, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke earned the epithet “Helicopter Ben” for doing essentially the correct thing, which was to adopt a policy, metaphorically speaking, of dumping vast quantities of money from the central bank’s helicopter onto the economy. By and large, it worked. Unemployment peaked at 10 percent in 2009 in the US, and now is at an historically amazing 3.8 percent, a 49-year low.

In Greece, by contrast, the European Central Bank controls the money supply. And the European Central Bank, by general consensus, responds to the cues of Northern Europe in general, and Germany in particular. Germany, unfortunately for Greece, right now has a 3.4 percent rate of unemployment, a 38-year low. The right thing for Northern Europe and Germany right now is to restrict the supply of money.

In Greece, by contrast, the European Central Bank controls the money supply. And the European Central Bank, by general consensus, responds to the cues of Northern Europe in general, and Germany in particular. Germany, unfortunately for Greece, right now has a 3.4 percent rate of unemployment, a 38-year low. The right thing for Northern Europe and Germany right now is to restrict the supply of money.

What I’m pointing out is that Greece and Germany have incredibly mismatched economies to share the same currency and monetary policy, to the terrible detriment of Greece in the midst of a massive depression.

Imagine now the gut feeling many Greeks must feel about the politics of this situation. You think there are political divisions in the US right now? You’ve noticed some resentment of possible foreign interference in our sovereignty? This sense that the German monetary policy keeps the Greek economy under its thumb with low growth, high unemployment, and high debt would naturally lead to resentment. Imagine if the Federal Reserve were controlled by a committee made up of financiers from Canada, the UK and the Moon, and they set policy with huge implications for the US economy. That’s how the Greeks feel.

Actually, it probably feels far worse than that.

On the island where I’m visiting this summer a statue proclaims the names of nine young men shot in 1944 by German occupiers on the island in World War II, as a warning against resisters. It wouldn’t take much stoking of nationalist resentment to make Greeks upset about their situation. Again, unemployment is worse that it ever got in the US during the Great Depression, for 5 years running.

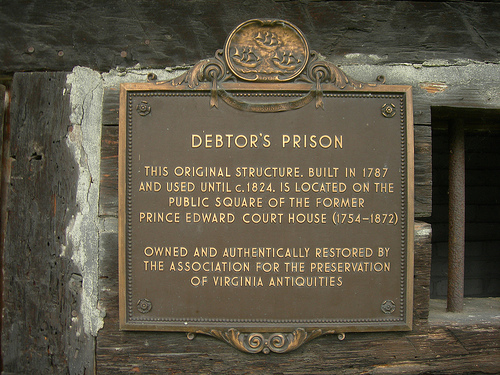

Next problem. Since 2009, Greece has suffered from an unsustainable national debt problem. The national government collects too little in taxes and owes too much to domestic pensioners and foreign debt holders.

Not only do the Greeks not control their own monetary policy, their fiscal policy – government policies of spending and taxation – are deeply subordinate to what’s referred to as The Troika – the leadership of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. In order to remain solvent, the Greek government has had to compromise its sovereignty to the Troika.

Meanwhile, the financial stress has fractured Greek politics. The

Neo-Nazi party known as the Golden Dawn holds 15 seats in the 300-person parliament and earlier was the third largest in parliament.

The ruling left-wing party Syriza was elected on a platform of opposing the Troika.

Before his election as Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras promised the Greeks an attractive combination of butterflies, moonbeams, and fairytales regarding taxes and spending. In other words, he wouldn’t raise taxes and he wouldn’t cut spending on pensions. The Greek electorate seemed to like butterflies and moonbeams. I mean, who doesn’t?

Before his election as Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras promised the Greeks an attractive combination of butterflies, moonbeams, and fairytales regarding taxes and spending. In other words, he wouldn’t raise taxes and he wouldn’t cut spending on pensions. The Greek electorate seemed to like butterflies and moonbeams. I mean, who doesn’t?

Once elected, Tsipras immediately reneged on his promise, agreeing to raise taxes and lower spending because, well, the Troika demanded it. Cleverly, he called elections right afterward. For some reason, despite the reversal of course and lies, his party won election again.

This week while we blissfully vacationed, a member of the Golden Dawn party called for the arrest of the Prime Minister and President, essentially asking for a military coup.

Anyway, vacation is so relaxing. I assume everything’s good back home?

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post:

Podcast: A Greek Businessman on the Crisis Part I – Government Bloat

Podcast: A Greek Businessman on the Crisis Part II – European versus Sovereign Power

Post read (165) times.