If a friend got into trouble with too much debt to the point of being sued by a bank, I would urge them to hire an attorney.

If a friend got into trouble with too much debt to the point of being sued by a bank, I would urge them to hire an attorney.

In Texas in particular, I urge that standard advice, and then double and triple it. Get thee to a lawyer!

There’s a weird thing you may not know about Texas and collecting consumer debt, like from credit cards. We think of Texas as a pro-business state. And so we might think that would put the power of laws and courts in favor of big banks at the expense of consumers and debtors.

Compared to other states, that just isn’t so. Texas is a very hard state to effectively sue and collect money in. And if the consumer hires an attorney, it gets very difficult indeed to force payment.

How do I know this? In my bad old investment days I used to work on the creditor side of things, trying to induce people to pay money they owed. Sometimes that meant pursuing debtors through the courts.

Consumer debts from Ohio, New York, Oklahoma, California? All so much easier to collect than debts from Texas. Texas was basically a nightmare for me.

But let me step back for a minute to explain different types of collections. If you haven’t been in trouble with debt owed to a bank, you might not know the differences.

Step one usually involves traditional collections efforts, which consists mostly of letters in the mail and phone calls. Besides dinging your credit through reporting the unpaid debt to the credit bureaus, a traditional collections firm constitutes a limited nuisance. Legally, the collector can’t call more than once a day. They can’t contact you at work. They can’t speak to anyone except you about the debt. If you don’t mind the hassle, traditional collectors can be ignored. Since most consumer protection happens at the federal level, there aren’t tremendous differences between collecting; this is the same across the states.

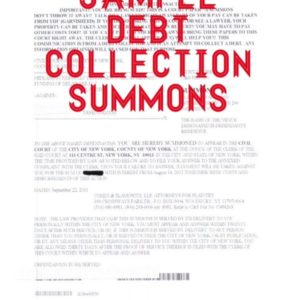

But in step two, a creditor initiates a lawsuit against the debtor. This is a more expensive step for a lender, but it ultimately gives the lender many more tools to collect the debt.

The creditor, through its attorney, seeks a judgment approved by court and judge. With a judgment in hand, which might take between a few months and a year to obtain, the debtor has much more at risk.

A court-ordered judgment allows a creditor to collect in more ways. In most states, if you have a job, the bank can garnish your wages, meaning force your employer to send money –- up to 25 percent of your salary — to the collections attorney. In most states if you own real estate, the collector files the judgment with the county. With a judgment as a lien on property, you generally cannot sell your property or refinance your mortgage without paying on the judgment. Finally, if you have any money in a bank account, the creditor can force the bank to turn over that money.

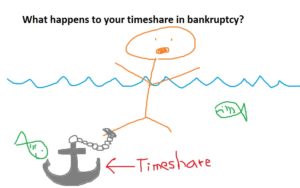

In Texas, however, a creditor can’t effectively do most of those things. Judgment creditors can’t garnish wages at all. And property liens and bank account garnishments can be fought very effectively with an attorney.

Benjamin Trotter, an attorney in San Antonio who represents consumer debtors who have been sued, or who have a judgment against them, described to me a wide array of tactics he uses to push a bank creditor to back off from bank accounts.

“Ninety percent of the success against these lawsuits is just showing up,” said Trotter. “Because you make the other side work on this, and they have to determine the cost and benefits of how much they want to put into these cases. Particularly for these lower threshold amounts, do they want to put all the documents in order to collect on a couple of thousand?”

To be more specific, creditors do not have the right to take the money from a bank account that comes from social security, insurance, or unemployment payments, nor money held jointly with another person. When attorneys like Trotter get involved, they can gum up the creditor’s process. It’s up to the creditor to figure out precisely where all the money in an account came from. That takes time and money to do. Creditors do that cost-benefit calculation and frequently back off.

To be more specific, creditors do not have the right to take the money from a bank account that comes from social security, insurance, or unemployment payments, nor money held jointly with another person. When attorneys like Trotter get involved, they can gum up the creditor’s process. It’s up to the creditor to figure out precisely where all the money in an account came from. That takes time and money to do. Creditors do that cost-benefit calculation and frequently back off.

When it comes to real estate liens, a debtor’s attorney can file to get liens removed from declared homesteads in Texas. (Note: This won’t work with non-homestead property.) But removing the judgment lien from the homestead can nullify one of the creditor’s most powerful tools.

By making judgment enforcement relatively toothless in Texas, the debtor’s attorney’s power is greatly enhanced. Since it’s so much harder to do all those things in Texas to collect debts, an attorney who represents a consumer debtor almost always can get a bank to negotiate a settlement.

I asked Trotter if he had advice against making rookie mistakes, say, for a debtor being sued who hadn’t yet hired an attorney?

“A lot of people will call up the bank or the bank’s collection attorney themselves,” Trotter cautioned, “So if you do reach out on your own to the bank’s lawyer, know that you are being recorded.”

If you talk to them, Trotter cautions, admit nothing.

He says, “especially when it comes to the statute of limitations, if you validate the debt, it could extend the statute of limitation, and put you on the hook of admitting you owe it.”

Instead of admitting to owing the debt, “Say something along the lines of ‘I’m not admitting that I owe this, but for the purposes of putting this behind me, I want to come to some sort of agreement,’” Trotter said.

I’d say get an attorney to do the talking for you.

In Texas, it probably will work.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle

See related post:

Ask An Ex-Banker: Medical Collections

Post read (591) times.