I learned about a timely investment tool from an article by Burton Malkiel in the Wall Street Journal this past month.

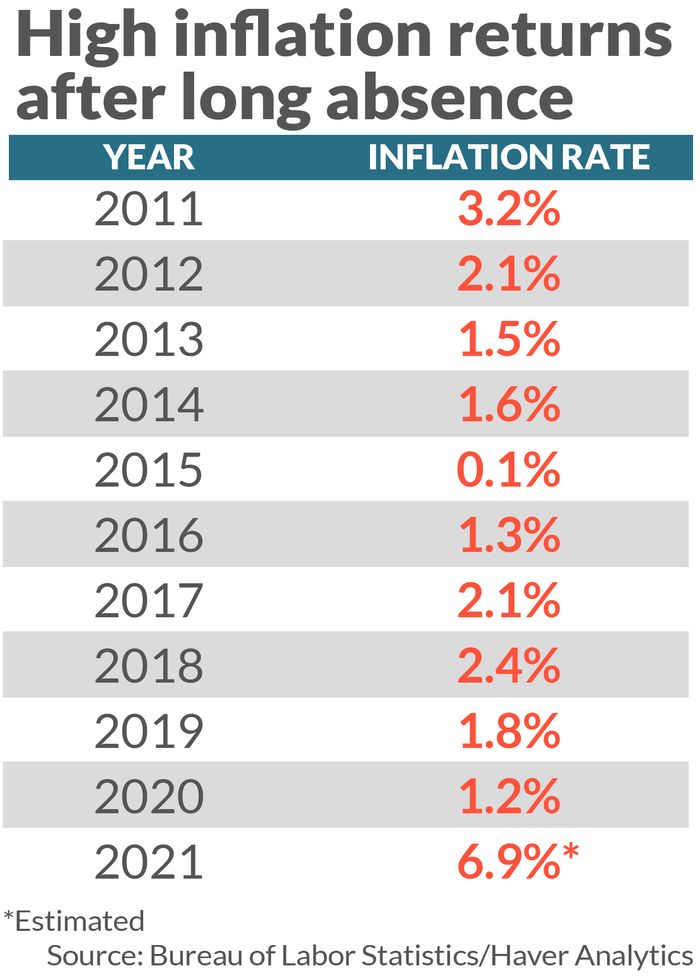

Timely, because observed, economy-wide inflation has finally hit us and prompted the Federal Reserve to acknowledge that “transitory” isn’t the right word for inflation anymore.

I don’t give investment advice here, nor should you ever take investment advice from a stranger who writes a blog or newspaper column. So this is not something you necessarily should do. Rather, I think it’s worth knowing about tools that may solve a particular worry of yours, particularly if it’s been nearly 40 years since we’ve actually experienced broad-based inflation.

Malkiel is best known as the author of one of my personal All Time Top Five Investing Books, A Random Walk Down Wall Street.

So for me – just like in those E.F. Hutton commercials that the over-50 crowd will remember – “when Burton Malkiel speaks, people listen.”

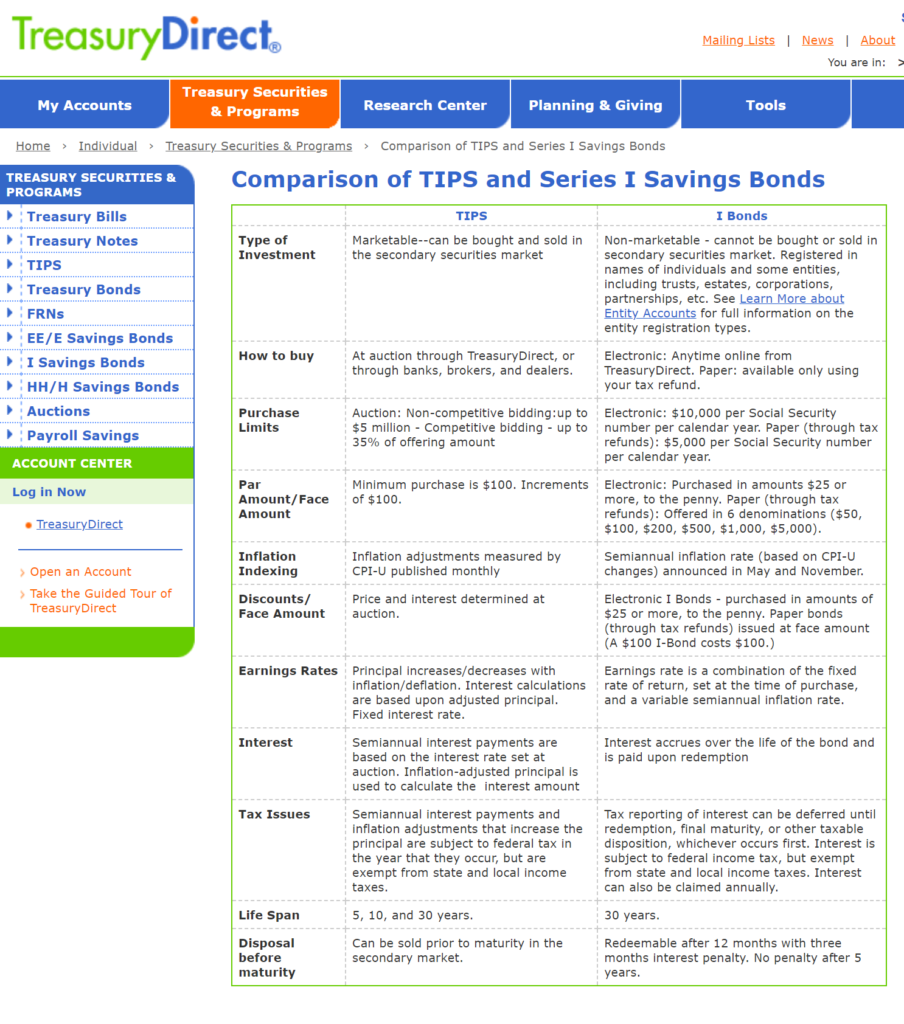

In his article, Malkiel introduced the US Treasury I bond as a tool that we should consider as part of their overall portfolio.

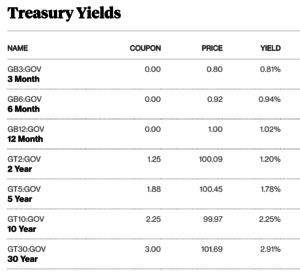

Here’s the part that makes I bonds quite sexy right now. Because the consumer price index jumped so much this Fall, the yield on I bonds is 7.12 percent. I bonds purchased in January 2022 will enjoy this fixed rate until July 1st. That is the highest interest rate that I bonds have offered since May 2000. The semi-annual yield reset will track the consumer price index in the future. After the next reset, the yield could very well go down, if inflation goes down. If it stays high, the I bond will keep a very nice yield, which is why it’s a plausible hedge against inflation. No matter what the inflation rate is in the future, the yield on I bonds can not go negative.

Institutional investors – big funds and insurance companies and banks – typically have looked to TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) when they worry about inflation. Since 1997, investors have been able to buy these bonds that pay a fixed interest but that adjust their principal upward in response to inflation, also as measured by the consumer price index.

The little guy has typically only been able to access TIPS through mutual funds. Because inflation has been so tame since 1997, TIPS have rarely been high yielding, but instead have offered a hedge against the “what if” scenario. And that “what if” has hardly shown up until recently. Returns over the past 10 years on a TIPS fund have been in the 3 percent annual range, before taxes, with the biggest boost to that performance hitting in the past two years.

Unlike TIPS, you would buy I bonds directly online from the US Treasury, without a brokerage company or mutual fund. They’re not saleable by a brokerage, nor by you. You buy them in increments from $25 up to $10,000 maximum per social social number, per year. They register in your name only, or the name of the trust or partnership buying it.

I bonds are designed for retail investors with a long time horizon, and do not work as well for a short-term trade. That’s because you will pay a 3-month interest penalty if you redeem after 1 year. Although they can’t be traded and are intended to be held for 30 years, you can redeem your I bond after 5 years without penalty.

Because interest accrues until maturity or redemption, you will pay income tax on the interest only at the end. The following fact is irrelevant for Texans, but the interest earned on I bonds is exempt from local and state income taxes, like traditional municipal bonds.

Speaking of traditional bonds, US Treasury or corporate bonds are the last thing you want to buy in an inflationary environment. In addition, US Treasury bonds offer a measly 0.5 percent to 1.8 percent right now. Even a basket of high-risk corporate bonds (what we’ve impolitely called junk bonds since the 1980s) only get you about a 4.5 percent annual yield. That’s unacceptable unless you enjoy locking in losses against the current observed rate of inflation.

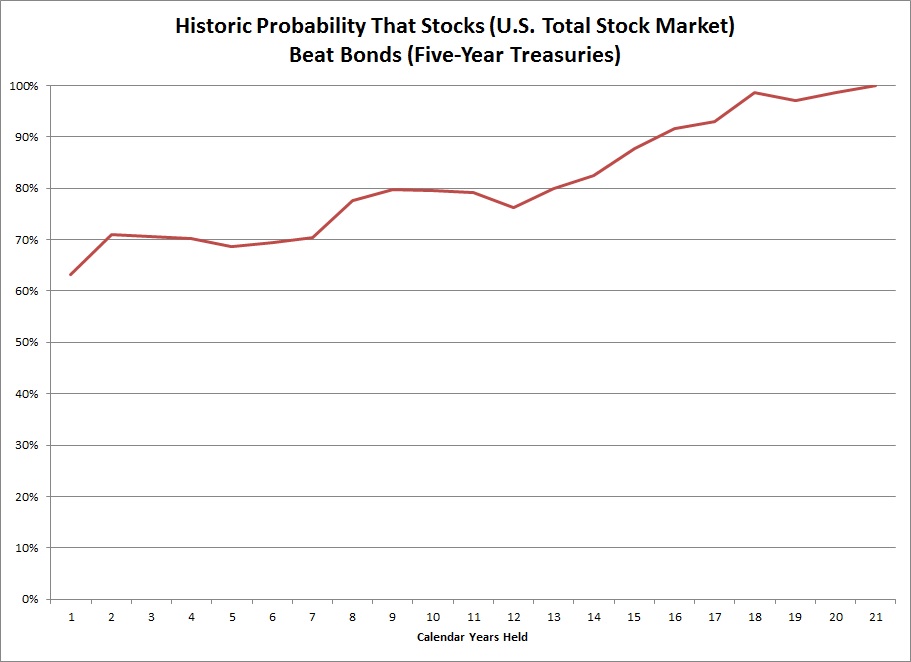

Maybe another concluding thought about this particular investment tool is in order. I, personally, will not be purchasing inflation bonds, neither TIPS nor US Treasury I bonds. I’m not actually that worried about inflation in my life or in the economy. I think my combination of real estate (my home!) and stocks (my retirement accounts!) will serve me fine under medium-level inflation. But I have a different risk appetite from most – my appetite is quite high. And I have a longish time horizon. I’m turning 50 this year so I have another 80 or so years to live (if my math is correct?)

I’m not deviating from my plan (Buy 100% equity index funds, never sell) but I mention this I bond product so that you’re a more-informed investor.

Also, you should read Burton Malkiel’s classic A Random Walk Down Wall Street. That is my strongest investment recommendation. I wouldn’t recommend any particular stock or bond to buy, but reading a classic like Malkiel’s book is highly likely to make you richer in the long run.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle

Please see related posts:

Book Review: A Random Walk Down Wall Street by Burton Malkiel

Never Sell – A Disney and Churchill Mashup

Post read (237) times.