More Happy Unintended Consequences

More exciting things (to me) keep unfolding from the ongoing financial education of my 8 year-old.

A little while back I took all of my daughter’s tooth fairy savings and invested it in Kellogg stock, a wonderful, awful, idea of mine to begin teaching her about investing.

Following that, my daughter realized she had no cash anymore, which she found a lot less fun than I did.

As a result, she asked for an allowance a few weeks ago, which reminded me of Andrew Tobias’ advice about allowances from his The Only Investment Guide You’ll Ever Need.

The Tobias allowance idea

In summary form, he advises paying ‘daily interest’ on a small nominal starting amount, over a period of 1 to 3 months, so that kids can viscerally feel the money-grows-money magic of compound interest.

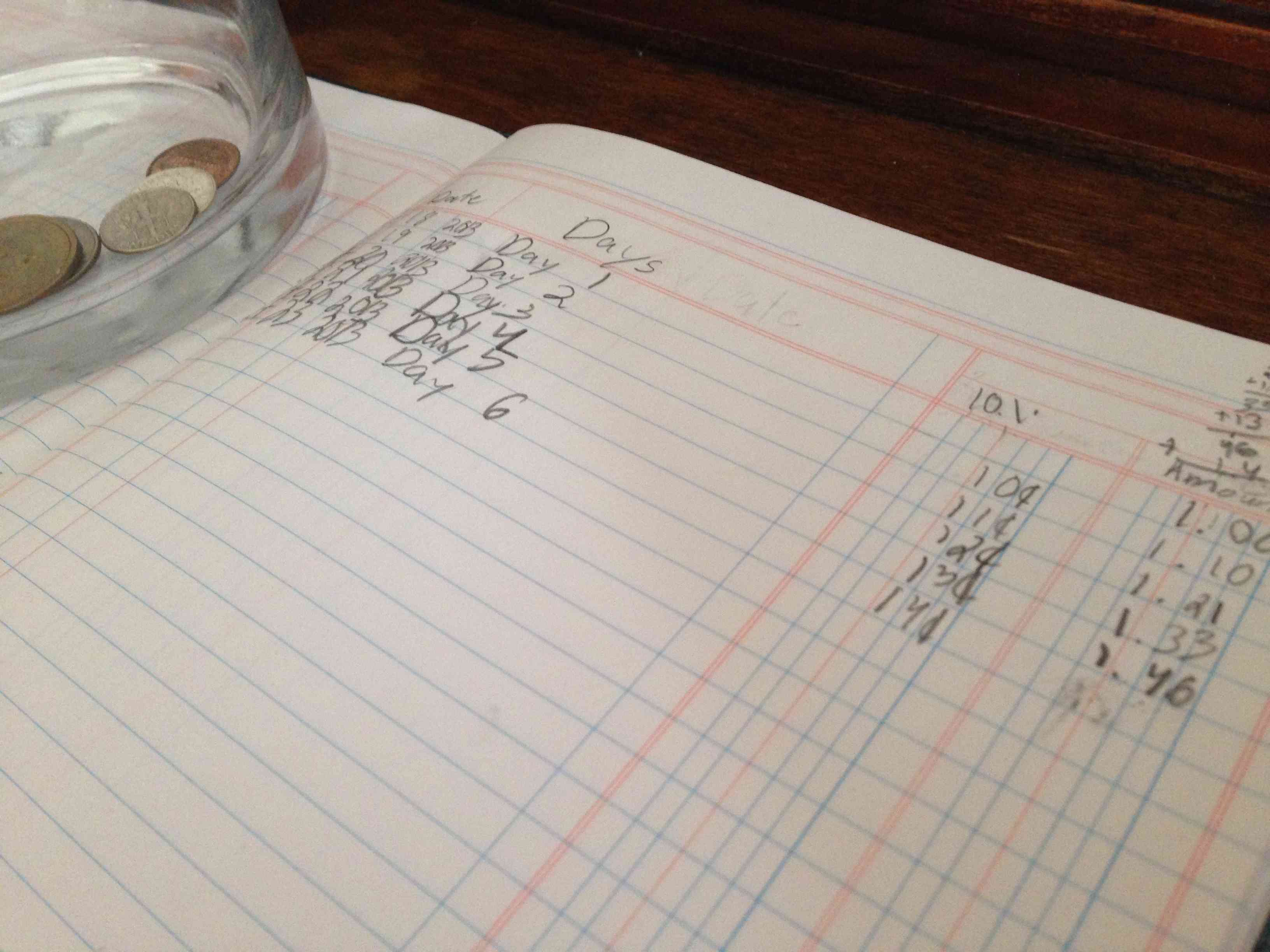

For my daughter I paid $1 into a glass jar on Day 1. Further, I have promised to pay her 10% in ‘daily interest’ on all money accumulated in the jar, over the course of 30 days.

For example,

Day 2 I paid 10 cents (10% of $1).

Day 3 I paid 11 cents (10% of $1.10)

Day 4 I paid 12 cents (10% of $1.21)

Day 5 I paid 13 cents (10% of $1.33)

Day 6 is today.

Your update on that project is as follows: This is even better than I expected, because of some unexpected consequences of my requirements.

My requirements[1]

I asked my daughter to document her 30 days of allowance in a lined journal.

One column shows the date, while the next column has the day number. The third column shows the daily 10%, while the final column lists the accumulated total in the jar.

I required her to calculate 10% of the total each day, as well as add up the totals on her own. If she wants to get paid, she needs to do the math. It’s a small step, but I’m so happy I required this.

A digression

I sometimes walk around my neighborhood wondering whether all of the world’s ills could be solved if people knew how to quickly and accurately calculate percents of things. Wouldn’t it all be better if we really understand discussions of percents of things?[2]

Am I the only one who thinks this? The Federal budget, poverty in America, tax policy, retirement savings, or properly tipping the bartender – I mean we’d all be better at all of these key problems if we could only calculate 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and intuitively understand what they mean.

When I see my daughter moving the decimal place over one numerical place to figure out 10% of her allowance jar savings, a little part of me jumps up and jauntily jigs with joy. Because this is a good life skill, and also SHE WILL BE THE NEXT FED CHAIRMAN TO SUCCEED JANET YELLEN.

The next math consequence – rounding numbers.

In addition to teaching compound interest, and teaching the calculation of percents, another math concept arose today. On day 6, she has $1.46 in the jar. Well, the contribution amount today isn’t 14 cents now is it?

My daughter is in third grade, and they’ve talked about rounding numbers, but this is probably the first time she’ll get to materially benefit from rounding up numbers. That’s right, 15 cents goes in the jar today. The numbers are starting to add up quickly.

I understand I derive an inordinate amount of pleasure from teaching my kid these math concepts. But is there anything more important right now?

Ok, fine, empathy.

But then after that?

Please see related posts:

Daddy Can I have an Allowance?

Daughter’s First Stock Investment

Book Review of Andrew Tobias’ The Only Investment Guide You’ll Ever Need

[1] My managing editor (aka wife) had allowance requirements for my 8 year-old too, such as “pick your crap up off the stairs and put it back in your room where it belongs.” But you can see that kind of stuff further described in the Mommys-Anonymous.com blog.

[2] We can all agree that the world’s ills could be solved teaching the calculation of percents, plus empathy. But if I had to choose between teaching empathy and the calculation of percents, well, shoot, which do you think I should do? I kid, I kid. I’m an ex-banker. OBVIOUSLY ITS CALCULATING PERCENTS.

Post read (9122) times.