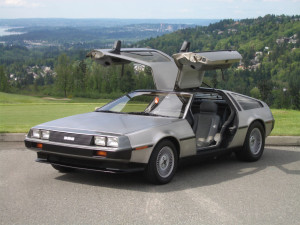

With the great economic freight train of spring 2020 brought to a screeching halt by COVID-19, our usual supply chains buckled, broke, and then fell off the tracks.

Our normal ways of satisfying our needs disappeared. In the midst of a scramble over the past month, in some ways we went back in time. In other ways, we went forward in time.

I reacted to shortages at the grocery store by getting in the habit of ordering a dozen eggs weekly through my gym, which has a connection to a local farm. The eggs are very delicious, and very expensive, compared to grocery store-bought eggs. I feel very close to the land!

I admire on social media my friends and relatives home-sewing their custom face masks from old scarves and bandannas. Stylish! Unique! Hand-crafted! It’s all very Etsy.com.

I bought a 5-gallon bucket of hand sanitizer from a friend who converted his whiskey distillery to the task.1

So the question becomes, will the legacy of COVID-19 be a return to a slower pace of economic life, recognizable from a century ago? A life full of locally-sourced eggs, hand-sewn clothing, customized distillery products and of course quality time with a small family unit? Seen from a certain angle, it’s all very Little House on the Prairie. Is that our post-COVID future?

No, that fantasy is silly. That train left the station long ago.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions philosopher Thomas Kuhn argues that big change comes not as a slow evolutionary process, but rather in sudden paradigm shifts. What we’ve all experienced and observed in the last month of social distancing is a massive jump forward – maybe by many years – into the future of certain economic processes. Below are just a few trends that COVID-19 will rapidly accelerate. COVID-19 causes this paradigm shift, rather than evolutionary change.

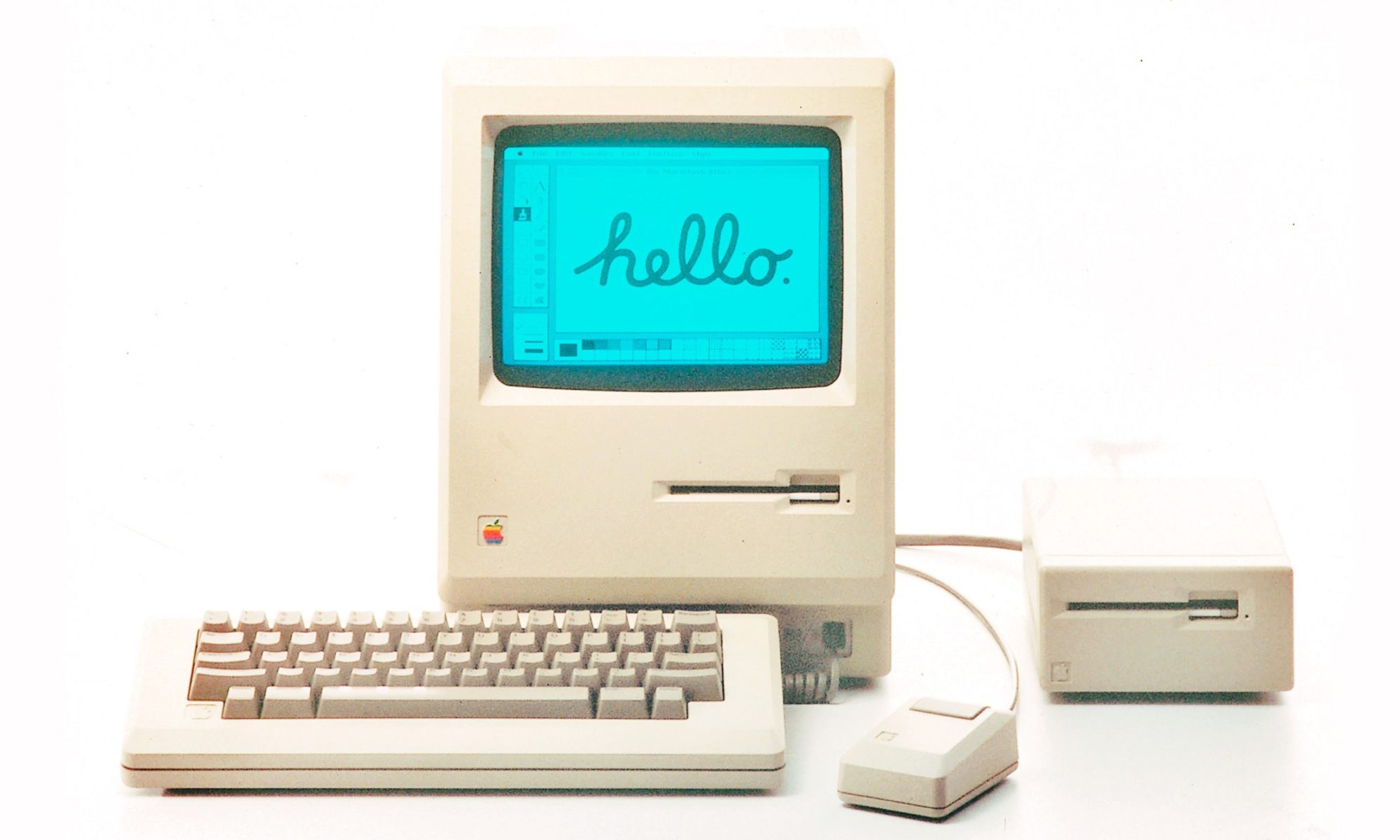

The revolution in education

Online learning this month has offered an insight into the future of school and learning. For the first three week of school shutdown, the public elementary school where my fourth grader attends has worked on providing technology to all of her classmates. That technology procurement was necessary because it’s impossible to start online work if kids in the class can’t get connected. So administrators have rushed to acquire and distribute iPads, hotspots, and internet access for families for whom that was previously out of reach financially.

Before COVID-19, they could never do much with online learning, because too many families would be left outside the digital divide.

Having solved that tech problem over the past three weeks, however, new online learning methods, assignments become both possible and necessary.

With the education world forced to adapt so quickly and so universally, will education ever be the same again? Will universities, for that matter, ever be the same? It feels like COVID-19 has forced a paradigm shift in what’s expected of teachers, schools, and kids.

The revolution in payments

I already used the touchless Apple Pay service before now. But I’ve noticed, to my frustration, that a huge number of retail establishments – like my local grocery store chain – never have the right kiosks to accept payment this way. If we understand that bills and coins are a germ-filled disease vector, and even that exchanging credit cards with a cashier is too much contact, then the contactless Apple Pay represents the future. COVID-19 may mark a sudden paradigm shift away from cash.

Apple, as always, sees the future before the rest of us do.

The revolution in retail.

Did we think Amazon’s deliver-to-the-door business model already threatened brick-and-mortar retail before 2020?

Of course. But the only reasonable observation to make now is that Amazon has accelerated its take-over of retail businesses in America. Much more brick-and-mortar retail will now die, much more quickly, in a step-change paradigm-shift way, not in an evolutionary way.

From the distance of time, let’s say two decades from now, my freight train economy analogy that I began this column with will seem even more quaint, and even more apt. We will look back at spring 2020 – before the COVID-19 transformation – and see the way we did things in 2020 as impossibly inefficient. Impossibly brutal, dumb, loud, linear, and tracked. Like a freight train that can only go from one point to another. So limited.

Our sleek, smart, creative, rocket ship economy of 2040 will have blasted off from 2020, no longer held back, no longer limited, by the rails of a freight-train economy.

Note: This post ran in the San Antonio Express News in April 2020…I’ve just been remiss in posting my stuff on Bankers Anonymous! Forgive me.

Please see related posts

The coming death of brick and mortar (2016 edition)

A small whiskey distillery near The Alamo that is also a family legacy

Post read (103) times.

- Next request to the distillery: Please hook me up with a 5-gallon bucket of moonshine to tide me over during this period of isolation, as I spend large amounts of indoor quality time with my family. ↩