While medical researchers race against time to find effective treatments for COVID-19, we have launched ourselves headlong into an economic experiment in federal policy on effectively treating a recession.

The experimental treatment so far is the recently signed $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Money for big businesses. Money for small businesses. Money for individuals. Is it too much? Is it not enough? Will it prove to be – in a phrase now used in many contexts – “a cure that’s worse than the disease?”

A primary mission of mine – as a writer – is provide language and categories around which we can discuss financial matters, as citizens. In vastly simplified terms, we could identify 3 theoretical approaches to fiscal and monetary policy in response to a COVID-induced recession, from the right, the middle, and the left.

On the right, the Austrian School and its most famous 20th Century theoretician, the Nobel Prize-winning Freiderich Hayek, would encourage limited government spending and a cautious central bank, in favor of freedom, individual action, efficiency, and ever-vigilance around inflation. Writing in the middle part of the 20th Century, Hayek warned against creeping Socialism and the centralization of economic power as threats to humanity. Bank lending of fiat currency – rather than relying on the solidity of an anchor-currency like gold – tends to artificially lower interest rates and overly expand the money supply.

The policy implications of the Austrian school is to interfere the least in business cycles, as they will work themselves out over time.

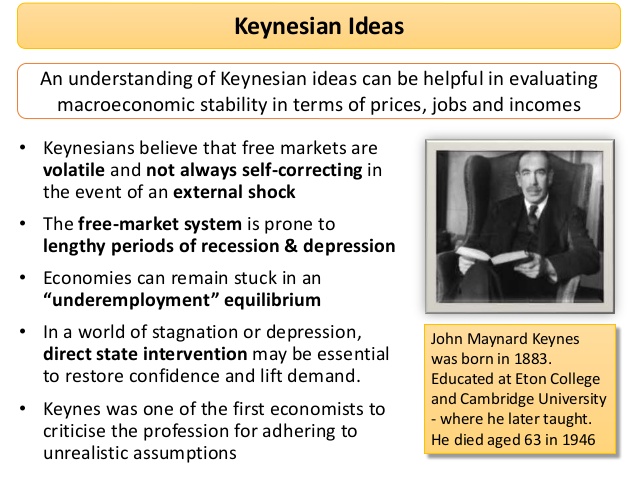

In the middle, policy makers advocate along themes established by John Maynard Keynes, who argued for a combination of robust government spending and easy money from the Central Bank, originally in response to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, a careful researcher of the Great Depression, followed that playbook in the 2008 Great Recession. And I would say – from a monetary policy standpoint when all was said and done – very successfully.

The left has recently coalesced around something known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Just as the Austrian school of thought and Keynesianism have variations, so too does MMT. But simplifying a bit, the big unifying idea of MMT is that governments that print their own currency like the United States do not have to worry tremendously about the problem of paying back debt. Controlling an unlimited supply of money can free policy makers from worries about a finite source of capital, or the classical economists’ worry of “crowding out” private borrowing and private enterprise. Both fiscal policy (taxing and spending) and monetary policy (the supply of money and interest-rate setting) should respond to problems by making money much more available, aggressively where needed. In stark contrast to the Austrian school, MMT points to a massive intervention of the government in the economy.

A key point of MMT – a point in which I am in agreement – is that debt owed by a government is not exactly like debt owed by a household or a business. Households and businesses do not create their own currency, so must always have a reasonable plan for repayment, or risk being shut down or punished by having assets seized by creditors. Governments that create their own currency, by contrast, need not fear creditors in quite the same way as households and businesses.

MMT theorists, accused of disregarding inflation, have argued that in periods of low inflation – like we’ve seen in recent decades, and like we usually see in recessions – policy can focus on more immediate threats, like underinvestment and unemployment.

I’ve been thinking about some of this in part because a conservative friend and reader handed me a copy of Freiderich Hayek’s The Road To Serfdom on March 18th, during what might be the last sit-down meal at a restaurant we will enjoy for months. Hayek’s worldview (or permit me to smoothly roll ‘Weltanschauung’ off my tongue) in simplest terms, is that the biggest enemy confronting society is government control of economic activity.

So where are we currently on the spectrum of policies – from the Austrian right, the Keynesian center, or the MMT left? As of this month we’re neck deep in a massive MMT experiment. That’s not what Congress and President Trump said out loud as they passed the CARES act. They would all deny it, if asked. But just to be clear: that’s what we’re all doing. The CARES Act was the most MMT experiment our country has ever tried. And it’s still early days yet in the COVID recession. As a betting man, I’d say more is coming.

And the weird thing was the near-unanimity of it all. Which also makes me nervous.

One reliable indicator of problematic policy in a democracy is unanimity, or near-unanimity of votes. Problematic because unanimity generally indicates votes forcibly taken, votes taken in fear, or votes taken under emergency conditions.

Like elections in the old Soviet times, in which the winner would earn 99% of the vote. Or like the Patriot Act of 2001, which passed the Senate by a vote of 98-1 in October 2001, following the attacks of September 11th.

We similarly saw the passage of the $2 trillion CARES Act by a 96-0 vote in the Senate, and the absence of anything other than a voice vote among a quorum in the House of Representatives, without a recording of who voted how. Friday March 27 was a weird day in Washington.

So Tea Party folks, just to clearly review. Your party – with a unified Republican Congress and Presidency – passed the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, expected to increase the federal deficit by $1.4 trillion, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The CARES act just passed – by a divided Congress and Republican President – will cost $2 trillion. What we should all agree on right now is that there is no fiscal and monetary conservative party in the United States. It does not exist. We’re all unified MMT leftists right now. I guess we’ll find out in a few years how we like it.

Not that we necessarily had a choice.

Would I have voted yes for the CARES Act, were I in Congress that day? Yes.

Do I think we’ll be instituting a form of Universal Basic Income within 6 months? Yes.

Do I think our fiscal and monetary policy might be a ticking time bomb – both because of our debt levels and inflation – for the United States? Also yes. [LINK to column on government debt spending:

Please see related posts:

We’re getting UBI and we’re never going back, after 2020

Government Debt – Ways to Think About it.

Post read (185) times.