Rather than say, “this is how you should invest,” I prefer to say (and write about) “this is how you should NOT invest.”

Rather than say, “this is how you should invest,” I prefer to say (and write about) “this is how you should NOT invest.”

I can think of at least three reasons for my preference.

First, I know many more terrible ways to invest than I know good ways.

Second, exotic bad ideas make for more interesting conversation (and reading) than boring good ideas.

Third, by focusing on the negative exhortation, I safely hide behind the critic’s shaming attack of “You didn’t do THAT did you?” rather than the advisor’s defensive apology, “I’m sorry I suggested you do THAT and it didn’t work out. But hey! The theory was solid!”

This is all a lead-in before I poke my head out of my turtle shell to give positive advice about how you should invest, before I quickly return to my more comfortable space of how not to invest.

How to Invest

Are you ready for the most important, boring, good idea on how to invest?

You should invest via dollar-cost averaging in no-load, low-cost, diversified, 100 percent equity index mutual funds, and never sell. Ninety-five percent of you should do that, 95 percent of the time, with 95 percent of your investible assets.

Phew, I said it. That paragraph right there is a trillion dollar financial advisory industry sliced, diced, chopped, shredded, sautéed, and reduced to two sentences, and served on a beautiful platter for you. If you don’t understand all the words, don’t worry, just print them out, bring them to your financial advisor and demand only that. Every time he tries to deviate from that plan, just point back to those two sentences and say, “I want only this.”

You’re welcome.

How Not To Invest

Ok, now let me retreat to my more comfortable critic’s shell and tell you how – given that central piece of advice – you should NOT invest.

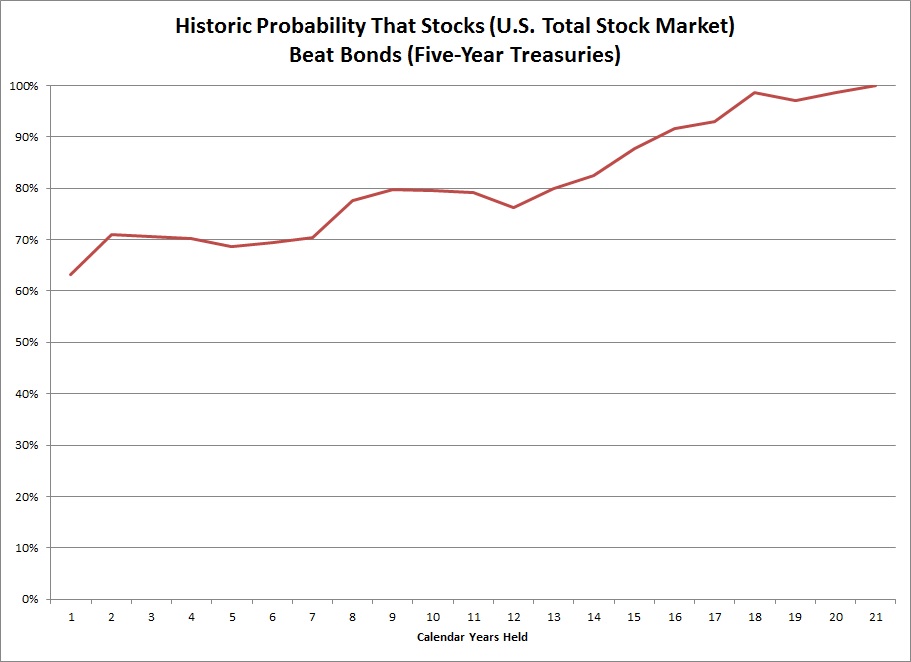

- You should not invest your money for less than 5 years. When I say ‘invest,’ I don’t mean buy some investment product with a view to selling it the next day, the next month, or even next year. I think five years is kind of the minimum investment horizon I’d endorse. Also, when investing, the best time horizon for selling is ‘never.’

- You should not invest in ‘safe’ products, like money markets and bank CDs, annuities and bonds. Since this contradicts most of what the banking and financial industry advocates, perhaps I should clarify this point. Money markets and banks CDs work wonderfully for saving money – to buy a fancy new pantsuit or a personal robot, for example, or some other essential purchase. Unfortunately, saving money offers almost no return on your money, and often a negative real return after taking into account taxes and inflation. Saving money is not the same as investing money. Annuities and bonds offer a wonderful psychological feeling of comfort. But that comfortable feeling is also not the same thing as investing. Parking money – when you can’t afford to lose any principal – is different from investing money. Investing money always involves the possibility of loss. Incidentally, I know your investment account is currently allocated to 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds (because everybody’s is.) I’m not your investment advisor, you’re not paying me one way or the other, so I don’t really care, but I’ll just point out that 40 percent of your investment account is poorly allocated.

- You should not invest in funds without checking the cost of the fund. Most of us would not dream of buying an ice cream sandwich at the Dollar Store without verifying its price first. I mean, I’ll take it out of the freezer and bring it to the cashier without knowing the price (maybe!) but I’m not too ashamed to ask ‘Hey, by the way, how much is this thing?’ (Although admittedly there are some things I wouldn’t do for a Klondike bar.) Can we have a show of hands from mutual fund investors who know the cost of the funds they bought? In my anecdotal experience, not even one in three investors knows the management fees of their funds. People who have worked in the finance industry usually know enough to ask, but even there I don’t think even one in two bothers to check ahead of time. FYI, it’s costing you a lot more than the price of an ice cream sandwich.

- Speaking of upfront payments, there is absolutely no reason to pay upfront fees for a fund, known as the fund’s ‘sales load.’ No reason at all. Do not do this. Oh, you didn’t know how much you’re paying in ‘sales load?’ See rule number 3.

- Don’t time the market. If you have investible assets ready to go right now into the market, just put them in the market, and forget what I wrote above about dollar-cost averaging. If, instead, you invest based on your monthly surplus, just set up autopilot investing from your paycheck or bank account and never alter that based on ‘timing’ concerns. There’s never a good time or bad time to be in the market. I mean, obviously there is, but there’s absolutely no reliable way you’ll know it ahead of time.1 Every academic study ever done concludes the same way: Timing is a mug’s game. You can’t win that way.

- If you’re not a financial professional, try not to spend too much time, energy, or brain space on this investing task. Simplicity and modesty can actually put you way ahead of the pros trying to do fancy things with their investment portfolios. Most of the exotic products don’t work better than the simple products, but they do tend to cost more, and they tend to go wrong in unexpected ways, at the most inopportune times. Keep it simple, smarty.

So that’s about it. If that all doesn’t work out for you, I’m sorry. But hey! The theory was solid.

A version of this appeared in the San Antonio Express News

Post read (5793) times.

- Well, the best time to be in the market is always thirty years ago. But you can’t get there from here unless you start today. ↩