A majority of people struggle to prepare financially for their retirement, but public school teachers and employees face a particularly difficult set of circumstances.

I’m enough of a fiscally hard-assed finance guy to think that every public school teacher should self-fund his or her retirement to supplement their pension plan, which for people in my state is the Teachers Retirement System of Texas (TRS). Unfortunately, there’s the grim reality facing many teachers about how hard this is to actually do. I learned a lot recently from my teacher friends about why that’s so.

My friend Dina Toland has worked as a public school teacher in Texas for 23 years and described the typical way she and her colleagues obtain their “retirement advice.”

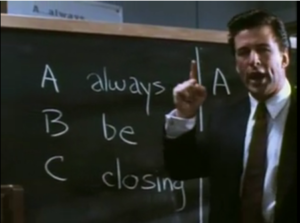

First, a representative salesperson for an insurance or investment management company gets invited, for some unclear reason, to a faculty and staff meeting, where they have a captive audience from which they can collect email sales leads by offering raffles or some other minor incentive.

The salespeople then attempt to schedule one-on-one teacher meetings using these leads, at which the pitch usually involves scaring teachers about their insecure retirement and the need for certain specific investment products. Thus made anxious, teachers are often urged to invest in variable annuities, which I consider one of the four horsemen of your personal financial apocalypse because of their high fees, illiquidity, low returns, and generous sales commissions for these same salespeople.

Dina was convinced to buy into this mess when she was a young teacher just starting out. Ironically, the salesperson herself was so inexperienced that she convinced Dina and her cohort of similarly clueless young teachers to take out too much money from their paychecks, such that they all had trouble paying their bills in subsequent months. Besides taking too much money, they all bought into these terrible variable annuities. As Dina says, how would they have known any better?

Dina was convinced to buy into this mess when she was a young teacher just starting out. Ironically, the salesperson herself was so inexperienced that she convinced Dina and her cohort of similarly clueless young teachers to take out too much money from their paychecks, such that they all had trouble paying their bills in subsequent months. Besides taking too much money, they all bought into these terrible variable annuities. As Dina says, how would they have known any better?

This problem afflicting teacher retirement planning isn’t limited to Texas. The New York Times ran an excellent 6-part series last year with provocative and true headlines like “Think Your Retirement Plan is Bad? Talk To A Teacher” and “An Annuity for the Teacher – And the Broker” about precisely these difficulties, featuring public school teachers in Connecticut who were sold products with this combination of high fees, low returns, illiquidity, and hefty commissions for insurance salespeople.

My friend David Nungaray, in his 6th year of teaching and administration in public schools in Texas, has a similarly discouraging story.

Early in his career, a representative salesperson of an insurance company was invited to speak to new teachers like him, at which he was of course urged to purchase an annuity. He did, to my chagrin when I later learned what had happened. This year he resolved to open up his 403(b) employee-sponsored retirement account, the next big option for self-funding one’s retirement.

Helping my friend David set up his 403b account was anything but easy and straightforward. David is himself extremely competent. But we agree this would never have gotten done without both of us working hard to do it. As a first step, David asked six of his colleagues in the public school system – chosen by David for their seeming prudence and likelihood to have a 403(b) account – if they had any advice for him. Only one of the six had ever signed up for a 403b account. Not an auspicious start. David then contacted his school district to look for help. Could David get any investment advice from his school district? No. The human resources department at his school district referred David to TCG Group, which administers all employees’ 403b plans for his school district, as well as many others in the state. The TCG Group website provides a list of 51 approved annuity and investment firms, with links to contact them.

David had no idea which investment firm to pick. Could TCG Group help? No, that’s not their job. They are 403(b) plan administrators only.

As a side note, I tried for three days to have a substantive conversation with folks at TCG Group, for the purposes of this post. Let’s just say they were as helpful and open with me as they were with David.

The next step was to pick an investment firm and to open an account. I helped him do that. Having done that, he returned to TCG Group to give them instructions to have 403b contributions deducted from his paycheck. Of course, then he needed to select an investment, or series of investments, at his chosen investment firm. That’s easy for me to help him with, so I did. But this hand-holding happened over the course of four weeks, with many barriers along the way. The barriers would have deterred a less determined employee, especially one without a friend willing to do it, in a non-conflicted way, for free.

Of course any of the investment firms could have “helped” him too, but he might have ended up with terrible annuity-like products totally inappropriate for the retirement account of a teacher still in his twenties. I’m all for self-funding and self-reliance as a theory, but I’ve become concerned about the reality of doing this well, for most teachers.

The stakes are high because most public school teachers in Texas – like those in many other states – can not count on Social Security in retirement, as 95 percent of school districts opt out of the federal system. So teachers fall back on the TRS and do little else.

If you are one of the over 1.5 million Texans who are members of the TRS, you should ask at least two big questions about your retirement. First, as my main safety net, is TRS financially strong? Second, will payments from TRS be enough to cover my needs in retirement, personally?

If you are not a member of the TRS, then as a citizen and taxpayer you should hope that state leadership is also asking important questions and having a good dialogue around these challenges and solutions. In a subsequent post I’ll talk about the finances of TRS, and that dialogue.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle

Please see related post:

Public Policy Debate on Teachers Retirement in Texas

Post read (457) times.