I wrote a few days back about how Reinhart and Rogoff’s serious, academic, review of past and prospective debt restructurings seemed to provide policy support for financial repression – such as capital controls, fixed currency regimes, highly regulated banks, and hidden taxes on savings through forced public pension investments.

This post highlights one of my favorite things – intellectual, counter-intuitive, irony. In particular I enjoy the irony of political affiliations that the Reinhart Rogoff paper inspires.

I don’t know Professors Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s political views, and in the most important sense they don’t matter. They’re economists, not political leaders.

In the post-2008 Crisis world, one of the ideological fault-lines has been to what extent governments should borrow and spend today, as a counter-cyclical buffer to the extremes of the economic downturn. Or conversely, whether the heavily-indebted governments of the developed world need to pare down their already-extensive borrowing, to avoid an even more disruptive crisis of fiscal insolvency.

Paul Krugman – from the political left – has carried the banner for more debt-financed government spending.

Regardless of the professors’ politics, the political right has adopted Reinhart and Rogoff’s work studying the history of debt restructurings as academic ammunition in favor of the budget austerity favored by the political right. This is logical.

To the extent Reinhart and Rogoff highlight fiscal profligacy and its consequences – for example in their book This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly and in their recent IMF paper – it makes sense that they find supporters in the austerity camp.

I guess that’s why I enjoyed the irony that I recently wrote about, namely that their recent paper appears to justify financial repression. The right-leaning austerity camp is probably the last group who would approve of an interventionist financial regime such as currency controls, explicit and hidden taxes on savings, and a heavily regulated banking sector.

Meanwhile, from the left, the critics of Reinhart and Rogoff’s history of debtors’ profligacy argue in favor of a much more severe regulatory regime when it comes to banking. The natural political affiliations seem flipped in this situation.

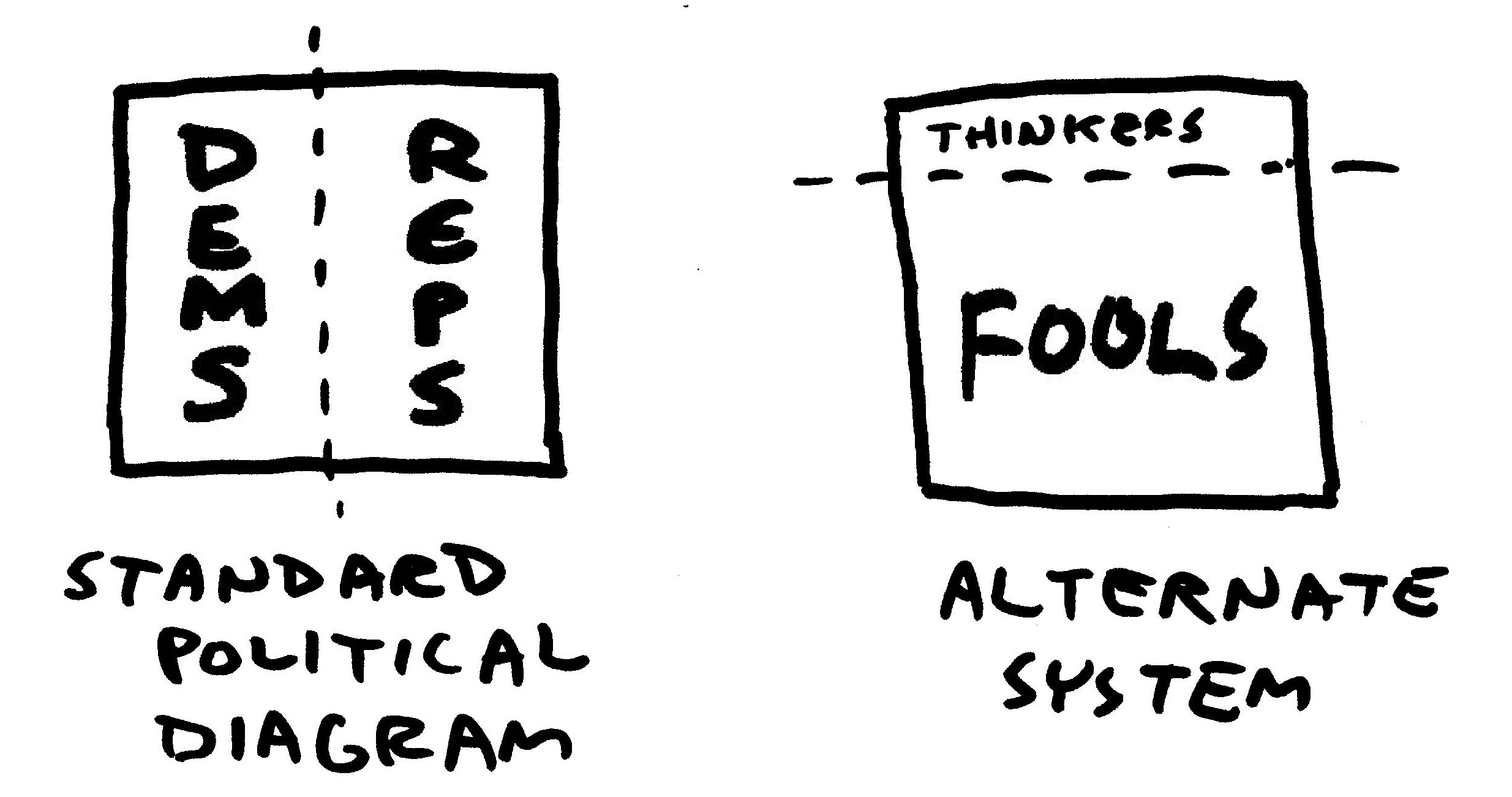

Of course, the challenge as always is to figure out what we really think about complex topics, rather than just adopt what ‘our side’ thinks on a complex topic. All of that reminded me of our tendency toward policy tribalism.

More on the irony of political affiliation

The best thing I read last week came from The Washington Post’s Ezra Klein, who highlighted our tendency to choose tribal affiliation over principal when it comes to policy preferences. It’s worth reading his article in full, but I’ll try to summarize Klein’s article.

First, Jesse Myerson wrote a lefty Op-Ed for Rolling Stone Magazine, advocating five policies

1. Guaranteed jobs

2. Guaranteed incomes

3. Higher taxes on landlords

4. A sovereign wealth fund to spread common ownership and

5. A public bank

Importantly, he cited Franklin Roosevelt, Martin Luther King, and some presumably left-leaning academics as supporters of his ideas.

Next, Dylan Matthews wrote a right-wing Op-ed for Ezra Klein’s Wonkblog, advocating the exact same policies, but citing conservative support for the ideas, such as The American Enterprise Institute, Milton Friedman, and Charles Murray.

The reaction: conservatives hated the first article and supported the second, while liberals, of course, praised the first and panned the second.

Klein goes on to cite the work of Stanford psychologist Geoffrey Cohen, who has shown that we consistently form our opinions about policies based on who we think supports the ideas – rather than the specific ideas themselves.

Do we really support the policy? Or do we just support it because our political tribe supports it? Are we thinking about stuff for ourselves or just figuring out which side our people are on?

To use a sports analogy (that I’m not sure really works): Do we really care about the guys on our team, or are we just rooting for laundry?[1]

I don’t know, but I will try to remember this.

Please see related posts on Reinhart Rogoff: Academia, Markets, and Click-bait

And the Reinhart Rogoff point that Financial Repression = less Financial Crises

[1] When he played for my team, Johnny Damon represented the paragon of lovable caveman-hood. But when he left for the Yankees, all that overdeveloped forehead (from, um, vitamin supplements I guess?) seemed gross. When he played for my team, Wes Welker was a virtuous, fast-as-a-tiny-quantum-electron, tight-end. When he crushed my spirit this past weekend with Satan Manning, well then. Welker is such a loser and a sell-out, in his goofy space helmet.

Post read (6708) times.