“Five Years from now, you’re the same person except for the people you’ve met and the books you’ve read.”

On Inequality

The Market Wonders, by Susan Briante. A book of poetry that compels us to consider the value of the stock market when compared to our human values.

Unintended Consequences – Why Everything You’ve Been Told About the Economy Is Wrong, by Edward Conard. I’m opposed to his politics but I must admit he offers the best description I’ve read of the mortgage crisis of 2008. Made me more sympathetic toward inequality, because I’m a contrarian cuss.

Nickel and Dimed – On Not Getting By In America, by Barbara Ehrenreich. Want to understand what it’s like to be part of the structurally poor in America? No? Well you won’t ever see it depicted in mainstream media, but here’s a good place to start.

Plutocrats – The Rise of The New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else, by Chrystia Freeland. I have a few quibbles on tone but this is a very interesting analysis of the extraordinary wealthy.

The Death And Life Of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs. This classic on urban planning policy from 1960 struck me as entirely relevant today. Jacobs writes convincingly on low-income housing policy, the problem with parks, the benefits of walkable cities, the importance of mixed uses, the essential nature of diversity in great cities.

Cities and the Wealth of Nations, by Jane Jacobs. By switching the economic unit of analysis from nations to cities, Jacobs offers still-relevant insights into development, inequality, currency regimes, and the decline of empire.

The Making of Donald Trump by David Cay Johnston. A review of thirty years of Trump’s businesses practices, associates, and personal style, from a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who covered him over the years. I wouldn’t say I was surprised by the revelations, but the details are important. Not a book about ‘inequality’ per se. But not entirely unrelated to the theme either, in the broadest sense.

Capital In The Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty. Sets the standard on data collection on wealth concentration in rich countries. Has a mathematical model that suggests ossification of aristocracy may be in our future, unless addressed through tax policy.

Words and Money, by Andre Schiffrin. A French-American from the traditional publishing world explains why for-profit behavior by media companies – in publishing, movies, book-selling, newspapers – are hurting society. Some proposed solutions which sound very European.

The Price of Inequality, by Joseph Stigliz. I started out sympathetic to his politics but his style of argumentation – hammer, hammer, hammer – is tedious. Also made me more in favor of inequality, because I’m a contrarian cuss.

On Personal Finance

The Automatic Millionaire by David Bach. A surprisingly well-done book on what may be simplest first two principles of investing: First, you DO have enough to invest. And the second principle: You HAVE to do automatic deductions.

Peace and Plenty, by Sarah Ban Breathnach. The worst personal finance book I’ve ever read, by the narcissistic, materialistic, unreflective author of Simple Abundance, a popular book from the 1990s endorsed by Deepak Chopra and Oprah Winfrey.

Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes, by Gary Belsky and Thomas Gilovich. The authors translate Behavioral Economics research with memorable anecdotes and illustrations to help us understand why we make sub-optimal personal finance decisions.

The Four Pillars of Investing by William Bernstein. At this point a personal finance classic. Great writing, great reviews of all the big ideas, great guidance to what we should all be doing with our investment money.

The Delusions of Crowds by William Bernstein. Bernstein anticipated 2021 and nailed it with this historical review of both religious and financial nuttiness that we humans are apt to repeat over and over again.

The Richest Man In Babylon, by George Clason. “Babylonian” fables written in the 1920s that retain timeless wisdom about of thrift, savings, skepticism, and self-reliance.

25 Myths You’ve Got to Avoid If You Want to Manage Your Money Right, by Jonathan Clements. Useful contrarian advice bursting the ‘myths’ of personal finance, from a long-time Wall Street Journal columnist

Your First Financial Steps – Managing Your Money When You’re Just Starting Out, by Nancy Dunnan. A personal finance book, from the mid-1990s, that did not age well. Anachronistic. Amazon Link to “Your First Financial Steps”

Secrets of the Millionaire Mind: Mastering the Inner Game of Wealth, by T. Harv Eker. Some interesting points to make on psychological limitations we may have about money, along with cognitive behavior techniques to overcome those limitations, but unfortunately told by a seminar-upselling jackass.

The Way To Wealth, by Benjamin Franklin. A greatest-hits of memorable aphorisms about thrift and industry by the founding father Benjamin Franklin, in his persona as Poor Richard.

Money Mindset – Formulating a Wealth Strategy in the 21st Century, by Jacob Gold. Probably a C+ from me. The ideas are fine (except he’s not directive enough on asset allocation) but the style isn’t that engaging.

Master Math – Business and Personal Finance Math, by Mary Hansen. This book’s focus on just the personal finance math, rather than the advice, makes it quite useful.

Think and Grow Rich, by Napoleon Hill. This personal finance classic offers ‘the secret’ to getting wealthy, and has inspired the world’s Dale Carnegies, Tony Robbins, Guy Kiyosakis. The ‘secret’ is not so hidden, and the prose is cheesy, but I’m willing to concede that the book could put you in the right mind-set for building wealth.

The Psychology of Money, by Morgan Housel. The best living finance writer with an instant classic of behavioral finance.

Investing Demystified: How To Invest Without Speculation And Sleepless Nights, by Lars Kroijer. A former hedge funder offers a simple, low-cost way to construct an effective global portfolio, keeping in mind the efficient market hypothesis (you don’t have an edge!) and the efficient frontier theory of portfolio construction.

A Random Walk Down Wall Street, by Burton Malkiel. The classic that launched the index fund market and popularized the efficient market theory. And its surprisingly interesting to read. You should read this!

How To Make Your Kid A Millionaire: 11 Easy Ways Anyone Can Secure A Child’s Financial Future, by Kevin McKinley. A financial planner offers practical advice for using time, plus savings, to provide future material well-being.

Simple Wealth, Inevitable Wealth, by Nick Murray. A personal favorite, showing how a calm and steady investment in equity mutual funds – over the long run – leads to inevitable wealth accumulation.

Behavioral Investment Counseling by Nick Murray. Another Murray classic, directed at advisors, to convince them that client behavior matters more than anything, and therefore how an advisors time, effort, and talent should and should not be allocated.

The Money Book for the Young, Fabulous, & Broke by Suze Orman. Solid advice for the target audience but I had a hard time getting past her annoying, robotic, schtick.

Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy And Its Consequences, by John Allen Paulos. An interesting and entertaining book on the importance of mathematical literacy, although I don’t think one of the intended audiences – innumerates – would ever read it.

Women, Money & Prosperity: A Sister’s Perspective On How To Retire Well by Donna M. Phelan. A personal finance book for women. Despite the pitch, the advice in the end is quite non-gender specific.

Stocks For The Long Run, by Jeremy L. Siegel. A classic in which Siegel present the 200+ years of data to show the overwhelming advantage of stocks over ‘safe’ investments when it comes to building wealth.

If Your Money Talked What Secrets Would It Tell, by Gary Sirak. Sirak offers real-life illustrations of his 8 Principles of Money, based on his career as a financial advisor for the last 30 years. He also argues persuasively that most of our trouble with money is caused by our own personal beliefs about money.

The Millionaire Next Door – Surprising Secrets of America’s Wealthy, by Thomas J. Stanley and William Danko. An influential (at least in my life) best-seller on the difference between having wealth and displaying wealth, and solid ideas on how to accumulate wealth.

The Millionaire Mind, by Thomas Stanley. Attributes of wealthy folks, such as their frugality, monogamy, purchasing habits, entrepreneurship.

The Only Investment Guide You’ll Ever Need, by Andrew Tobias. Funny and Useful, it’s a personal finance guide that actually lives up to its hyperbolic name.

My Vast Personal Fortune, by Andrew Tobias. Funny, quirky, and revealing anecdotes on real estate and advertising. Features Tobias’ obsession with auto-insurance.

Mathematics Standard Level for the International Baccalaureate, by Alan Wicks. I didn’t actually review this book, but just referred to it in my discussion of compound interest. The International Baccalaureate is how I learned about “Sequences and Series,” the mathematics behind compound interest. Also, this was written by my high school advisor and math teacher, so you should buy it!

On Business and Wall Street

Bailout – An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street, by Neil Barofsky. Barofsky, a personal hero of mine, blasts his way out of Washington DC, where he served as top financial cop for the 2008 bailout known as TARP.

Bad Blood – Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup by John Carreyrou. Best book on business in the past year and a great guide to how to spot fraud – which is a problem of our time.

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley’s Pursuit of Power by Max Chavkin. The first review in my series on our new billionaire philosopher kings. Peter Thiel has made some brilliant investments. He is also not a good guy. It’s his “nazi curious” leanings that make me particularly nervous.

The House of Morgan, by Ron Chernow. Fascinating history of the origins of JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley and Deutsche Bank (which absorbed the UK’s Morgan Grenfell). Even does much more in a few short chapters on recent history to explain how Goldman Sachs “came to rule the world,” than does Cohan’s book by that title.

Money and Power – How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World, by William Cohan. Cohan doesn’t answer the question in the title, and he cherry-picks a series of embarrassing episodes from Goldman’s history to offer it up as a scapegoat. The one useful section is his chapter on the mortgage department, in the years just prior to Crisis of 2008.

The ChickenShit Club: The Justice Department and Its Failure to Prosecute White-Collar Criminals, by Jesse Eisinger. Eisinger explains in detail why nobody went to jail as a result of the mortgage crisis, with specific focus on the weakening of the Justice Department’s will to aggressively prosecute individuals and companies after the Enron/Arthur Anderson debacles.

The Intelligent Investor, by Benjamin Graham. My kids will be reading this when they get old enough, because, 65 years later, it’s still fresh, and it will still be fresh in another 15-20 years.

The Hard Thing About Hard Things, by Ben Horowitz. Horowitz led his company through harrowing crashes and extraordinary success. He describes the painful decisions and gut punches of being CEO during the bad times. The latter-half of the book is less interesting, but the first part is intertwining and useful.

Systems of Survival – A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics, by Jane Jacobs. This isn’t about Wall Street, but rather about two interdependent systems of survival. Guardians (government functions) and Commercials (business functions) work well together but operate by separate precepts. Each has its own internally consistent moral code, but the breach and mixing of precepts can lead to monstrosities. I love this book as it practically explains everything you need to know about Left-Right/Democrat-Republican/Government-Business debates.

Flash Boys: Not So Fast by Peter Kovac. In insider from the high frequency trading world explains how Michael Lewis got so much wrong in his book Flash Boys.

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay, by John Lanchester. Lanchester is a super-clear and entertaining writer who explains the 2008 Crisis better than most.

Boomerang – Travels in the New Third World, by Michael Lewis. The silliest of Lewis’ Wall Street books, but nevertheless entertaining cultural snapshots of countries in the 2008 Crisis.

The Big Short – Inside the Doomsday Machine, by Michael Lewis. Funny and accurate review of the 2008 Crisis, in which Lewis does what no other journalists did – he makes the short-sellers the heroes.

Liar’s Poker, by Michael Lewis. The original classic. Start your Wall Street reading here, about Lewis’ short stint as a bond salesman, at Solomon Brothers, in the mid-1980s.

The Lean Startup by Eric Ries. Redefining the metrics of startups, and a whole new way of thinking about them. Don’t start a company, instead start a series of experiments to test your business hypothesis.

Where Are The Customers’ Yachts? by Fred Schwed. I had not expected this to be as funny as it was. Somehow, it turns out I dig 1940s financial humor, with some sly lessons on how Wall Street really works.

The Green And The Black, by Gary Sernovitz. Funny, informed, complex – A great overview of the implications of the shale revolution, aka the fracking revolution in the United States.

Too Big To Fail, by Andrew Ross Sorkin. Should be titled “Too Connected to Criticize” as Sorkin protects his present and future sources – the Wall Street CEOS of 2008 – from any criticism or real analysis of their responsibility for 2008.

Black Swan – The Impact of the Highly Improbable, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Taleb explains how the unexpected tends to shape everything, and our models never see the unexpected before it’s too late. Also, his timing on this book, right before the 2008 crisis, was awesome.

Fooled by Randomness, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Taleb’s first book blasts the traditional Wall Street world-view with his empirical skepticism and brash, take-no-prisoners, style.

Fiction

The Lives Of Animals, by J. M. Coetzee. A challenging, only semi-fictional philosophical exploration of the moral relativity of animals, compared to humans. Are we perpetuating an unthinking Holocaust on animals? Accompanying essays help flesh out the ideas.

The Pickup, by Nadine Gordimer. A novel exploring the immigrant and emigrant experience, and maybe, the impossibility of true understanding between people.

The Mystery of the Invisible Hand by Marshall Jevons. Two economists write this series of murder mysteries in which an economist applies economic theory to catch the criminal. This one takes place in San Antonio TX so I had to read and review it.

Capital, by John Lanchester. This book review, by Michael Lewis, contains great observations about English writing, and English attitudes towards capitalism.

A Conspiracy of Paper by David Liss. Explore 18th Century London stock markets just prior to the crash of the South Sea Company, as proto-private eye Benjamin Weaver investigates stock fraud and the death of his father. Fun stuff!

The Earl Next Door: The Bachelor Lords of London by Charis Michaels. American heiress Piety Grey battles scheming relatives and a literally falling-down London townhouse, while navigating the romantic pull of the Trevor Rheese, the Earl next door who thinks he just wants to live alone, unencumbered by responsibility for others.

Undermoney by Jay Newman. A prescient novel about Deep State power brokers, mercenaries, murderous kleptocrats in Russia and New York City. Newman somehow has the chops to describe their world in a way that feels like he knows what it’s like. Also, Newman is a bad ass hedge funder, so definitely has experienced some of this first hand.

Going Going by Naomi Shihab Nye. I reviewed this young adult novel in part because it takes place in my neighborhood and in part because it gave me a great excuse to discuss some meditations on what makes for a good city, and a good life.

The Turtle of Oman, by Naomi Shihab Nye. We brought this young adult novel on a trip to Big Bend National Park, which happens to be the perfect place to experience Oman. My older daughter and I enjoyed this tremendously.

The Way We Live Now, by Anthony Trollope. A book review by a friend, of a favorite book and favorite author, featuring the 19th Century British Bernie Madoff.

Theory of Knowledge

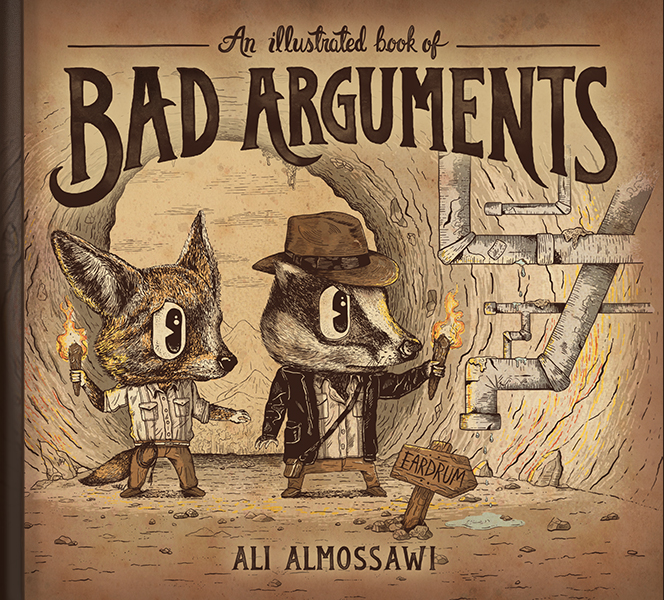

An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments, by Ali Almossawi. Almossawi’s online book is a pleasurably illustrated taxonomy of terrible logic, of the kind we so often hear from political pundits or members of the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex.

Risk Savvy, by Gerd Gigerenzer. Ultimately disappointing book that has some points to make about the limitations of building complex risk models for highly complex systems. But too much seems to be culled from presentations to rooms full of doctors, or something, and I was bored. I’d prefer to go with Nate Silver any day.

Dark Age Ahead, by Jane Jacobs. One of my favorite authors, with a title that made me need to read it. Jacobs has a theory of what will break civilization apart, and its all plausible.

Help, Thanks, Wow by Anne Lamott. Not really related to finance or even theory of knowledge. Just a meditative book that struck me as important to read and review. I highly recommend it if you need a good cry.

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail – But Some Don’t, by Nate Silver. Silver argues that applying Bayesian probabilistic thinking to a wide range of complex phenomena like sports betting, weather, earthquakes, Texas Hold ‘Em Poker, and politics help us understand the present and forecast the future far more than most legacy models we work with.

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden

Snowden betrayed the US and the intelligence community for a higher cause. I find his arguments utterly compelling. We are not thinking hard enough about the implications of the new surveillance society and surveillance marketplace.

Post read (10148) times.