A sometime gold-coin buyer and a frequent reader of Bankers Anonymous sent me a message a few days ago, linking to the CNBC headline “1930s-style debt defaults likely, says IMF,” and with the simple question: “Mike – True?”

A sometime gold-coin buyer and a frequent reader of Bankers Anonymous sent me a message a few days ago, linking to the CNBC headline “1930s-style debt defaults likely, says IMF,” and with the simple question: “Mike – True?”

Harvard economists Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff’s latest paper, commissioned by the IMF and published in December 2013, re-raises the specter of sovereign default in the so-called ‘developed world,’ warning of restructuring, restrictive capital controls, and debt write-offs.

Their paper was rewarded and echoed with headlines from Business Insider like “Extreme Debt Means 1930s-Style Defaults May Be Coming to Much of the Western World” and CNBC’s “1930s-style debt defaults likely, says IMF,” the headline that prompted my reader’s email to me.

This seemed like a great opportunity to reflect on the problem of different, confusing, contradictory messages constantly streaming from the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex.

Academia, Click-bait, and Markets

Those headlines, loosely based on the Reinhart and Rogoff IMF paper, are a great example of the giant gulf between financial academia, click-bait, and actual markets. Each information source follows its own rules and logic – but mixed up together provide a cacophony of worse-than-useless dis-information.

First, academia on its own terms

Professors of international economics should consider a wide variety of scenarios, and they should present historical data, as Reinhart and Rogoff have done, with their book This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly.

[I confess I have not yet read this, but I suspect I will find this a useful addition to other books I have enjoyed on sovereign debt defaults, such as A Century of Debt Crises in Latin America: From Independence to The Great Depression 1820-1930 by Carlos Marichal.]

I enjoyed the Reinhart and Rogoff paper, with its useful historical data, reminding readers that sovereign debt defaults in Europe are not particularly rare. In addition, sovereign defaults sometimes come hidden in sheep’s clothing – as when a combination of capital controls, high inflation, or forced ‘savings’ from captive sources such as workers’ pensions effectively bail out overly indebted governments.

As a former emerging markets bond guy I read Reinhart and Rogoff’s work with much interest. Here’s a summary of their main points, and my reactions:

- Drastic sovereign debt restructurings are historically more common than many realize, and come in a variety of forms. [Totally agree]

- Financial repression, while brutal and inefficient, probably reduces financial excess, and therefore financial crises. [Totally agree]

- The 5 year-old crisis we are in will involve more explicit restructuring of sovereign debt in the so-called ‘developed’ world, presumably peripheral Europe. [Mmm. Squinting. That depends. Doubtful.]

- We will see a return of ‘financial repression’ in the ‘developed world.’ [I see no evidence of this. Or, I guess it depends how you define ‘financial repression.’]

But what about the click-bait?

Reinhart and Rogoff are legitimate economists (at a reasonably decent University) so it’s not surprising that they have produced serious work on historical sovereign debt restructurings. I wonder, however, to what extent they anticipated (and even encouraged?) the click-bait aspect of their paper.

“1930s-style debt defaults likely, IMF says” is a totally misleading version of their report.

“Ex-Goldman bond salesman may make billions blogging his random opinions, says blogger,” is a headline I could write about myself, but it would have as much relationship to the probabilistic truth as that CNBC headline has to the IMF report.

Unfortunately, CNBC – and the rest of the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex – runs on nonsense click-bait, so people like my reader who sent me the email query get pummeled with emotionally-charged or scary bullshit, on an hourly basis.

Market Data

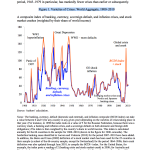

How do I know that – on a probabilistic basis – both the click-bait headline as well as points 3 & 4 of the Reinhart-Rogoff paper can be safely ignored?

Because what neither academia, nor the click-bait-setting members of the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex typically take into account is that we have a ton of aggregated financial information available in markets about exactly their topic. Right now. At all moments.

The bond market

At any given moment – with updates on a minute-by-minute basis – the most–informed people in the world on sovereign risk – with the most to gain or lose financially – are indicating the probability of default on all sovereign debts.

Bond traders – at mutual funds, hedge funds, banks, insurance companies, and broker-dealers – control the flow of capital into or out of investments in sovereign debt.

Yield or bond spread indicate aggregate market perceptions of risk by the most knowledgeable and interested people in the world.

The constant buying and selling of bond traders sets a price, in yield terms, that tells us a lot about what the odds of default are. The higher the yield, the higher the controller of capital is demanding to take the risk of the bond. In aggregate, the self-interested decisions of bond traders give a very full view of the total risk associated with these bonds.

The most common way bond traders compare the relative risk of sovereign debt is through a ‘spread,’ which means the additional yield investors receive over the yield of a riskless bond yield.[1] A 1% bond yield spread, or as bond traders would actually say, “100 basis points”[2] spread over an equivalent riskless bond, indicates that highly informed and highly interested investors find the bond mildly, but not extraordinarily, riskier than a ‘riskless’ bond

Most of us do not see the minute-by-minute information on government bond spreads but we can access it, updated at least daily, on the global government bond yield pages of financial news sources like The Financial Times or Bloomberg or The Wall Street Journal.

Why so much about the bond markets?

Why am I going into this excruciating detail about the bond markets? Because if you know something about how the bond markets work, and what information they convey, you can interpret both the Reinhart-Rogoff thesis on defaults and the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex’s click-bait headlines for what they are.

In sum:

Reinhart-Rogoff: Improbable

CNBC’s headline: Nonsense

How do I know this? Because the bonds markets give us bond spreads on the sovereigns they reference. Here are some select 10-year bond spreads this week from The Wall Street Journal’s global government bond page:

Italy: 97 basis points (less than 1% yield premium)

Portugal: 225 basis points (2.25% yield premium)

Spain: 88 basis points (less than 1% yield premium)

The bond market is saying, with these spreads, that it finds these European bonds mildly risky, but not terribly risky. Default, while possible, is highly improbable over the next ten years.

Of course, Greece already restructured its sovereign debt, so Reinhart-Rogoff’s ‘prediction’ came true. But since they published their ‘prediction’ in December 2013, however, they really can’t take credit for being nearly 2 years late.

So, no, 1930s-style defaults are neither likely to happen nor likely to be widespread, as implied by the IMF paper, and by CNBC’s headlines. Of course, anything can and will happen with markets, but the smart money’s not betting on that, and you shouldn’t either. Leave the fear-mongering to Harvard economists and click-bait headline writers.

Please see related post: The biggest, mostly ignored, point of Reinhart Rogoff’s IMF paper.

[1] Among bond traders primarily trading in US $ Currency, a ‘riskless bond’ for the purpose of determining bond spread, is usually a similar maturity US Treasury. Bond traders in Europe or Japan might use a different riskless bond as the basis for comparing risk in their own currency. We can argue about whether US bonds, or Japanese bonds, or German bonds are actually ‘riskless,’ and traders do, but traders also need a convention for comparison, so US Treasuries often serve that purpose regardless of whether its truly ‘riskless’ in the absolute sense.

[2] A basis point is 1% of 1%. Hence, 100 basis points for every 1% in yield or yield spread. If we say 5 basis points, or 5bps, (pronounced “5 bips”) that means 0.05% in yield, or spread terms.

Post read (15815) times.