We’re all about to get dunked[1] by the US Presidential race in a deep-water tank of Texas exceptionalism.

With a year-long GOP primary season ahead of us, get ready for Texas Senator Ted Cruz to explain how extremely small government (plus God!) serves us best. Also, prepare for Texas native son (now Kentucky Senator) Rand Paul to explain the same, but without the God part. We can look forward to former Texas Governor Rick Perry pitching his Texas economic miracle to the rest of the United States. And do not forget GOP favorite Jeb Bush who – like his younger brother W. Bush – grew up in scenic Midland, TX.

Even if you regard Texas with extreme prejudice – as I did before moving here in 2009 – you can’t avoid its prominence as the blueprint of Red State plans for the rest of the country.

I read Erica Grieder’s Big, Hot, Cheap, and Right: What America Can Learn From The Strange Genius of Texas as a kind of primer on the GOP Primaries.

If you’re an East or West Coaster who mostly learns about Texas from the NYTimes’ Gail Collins’ periodic columns on the biggest little state in the Union, I recommend Grieder’s deeper dive into some of the state’s colorful history, characters and traditions.

I read with most interest the parts of her story concerned with the ‘Texas Miracle’ and in particular Texas’ curious tradition with respect to the government’s proper role in economic development.

Here’s the thing that’s struck me since I arrived, and Grieder concurs: Texas political leaders do not actually pursue free-market economics in practice. There’s a strong tradition and ongoing practice, in fact, of the government picking winners and losers in the marketplace.

Before moving to Texas, I associated the rugged libertarianism of, say, Ted Cruz and Rand Paul, with the idea of government’s limited role in an economy. Yet time and again I’ve noticed that Texas governments – both State and City – take very seriously their mandates to subsidize particular businesses and particular industries.

‘Limited government’ in Texas really means limited government services to households, but it does not preclude the government from picking winners among businesses.

Elected officials – both Republicans (at the State level) and Democrats (who dominate all of the major cities in Texas) – always couch these targeted subsidies to businesses in terms of ‘jobs growth.’ The thinking, I guess, is that what’s good for a business owner is generally good for employees, since business owners are ‘job creators?’

As Governor, Rick Perry championed the Texas Enterprise Fund, a general purpose ‘economic development’ fund which handed out $507 million to ‘promising’ companies and institutions, specifically linked to ‘job creation’ achievements.

The State Auditor’s report in September 2014 found “control weaknesses” that made it impossible to verify ‘job creation’ claims by Perry government. The Auditor also found applications from private companies for funds to be insufficient and non-compliant with the original requirements of the Enterprise Fund. As Grieder reports in her book, many recipients of Enterprise Fund money, perhaps unsurprisingly, donated generously to Rick Perry’s campaigns, as much as $7 million to Perry’s reelection funds and the Republican Governors Association.

None of these results are surprising to observers of the Fund. What is surprising is Perry’s supposed allegiance with free-market, low regulation, limited government approaches, while spearheading the Texas Enterprise Fund.

The New York Times reported in 2012 that Texas under Perry has the highest rate of tax incentives targeted to specific companies of any state in the nation. Again, not surprisingly, there’s a strong link between beneficiaries of tax breaks and contributors to state officials, as reported by the New York Times.

But this Texas tradition of picking winners and losers in the marketplace is not limited to the GOP. The stakes are lower at the local level, but seemingly just as common.

Among the Democratic-controlled city where I live, every other week it seems a city or county ‘economic development’ group hands out a combination of targeted tax breaks or grants to a particular company.[2] Sometimes my city’s economic development team even directly invests in the equity of startup companies[3], which strikes me as, basically, insane.

This type of government-driven economic development violates everything I believe about:

- How actual economic development happens

- How winners and losers in an economy should be sorted

- How business owners actually decide to ‘create jobs’ or not ‘create jobs,’ in their businesses

- How government should best interact with private business

- How natural conflicts of interest between public office holders and private capital controllers should be mitigated.

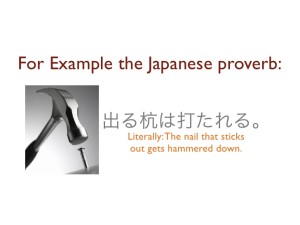

Yet, Texans on both side of the political spectrum don’t seem bothered by these ‘Texas Miracle’ tactics, at least as observed in the press or at the polls. This tradition of direct subsidies to chosen industries and companies – as described in detail by Erica Grieder’s book – does not seem to elicit the kind of visceral reaction it would back where I come from.

Here in Texas, this is all frequently described as ‘incentivizing job creation.’ Where I come from, it’s usually called corruption.

Erica Grieder’s tale of Texas’ peculiar history, characters and economic power cover a wide range of topics, but I appreciated most these parts focused on this peculiarity of Texas government and culture.

I’ll be watching the GOP primaries closely with an eye to how this plays out among all of Texas’ native sons.

Grieder covers other ground in her book as well.

If you’re already a Texas resident with a reading habit – I read Texas Monthly, Texas history books, plus the local paper, – many of Grieder’s story lines and anecdotes will seem familiar already.

At times the book reads like a review of recent political journalism. Grieder’s not providing a ton of data in these sections, but rather journalistic narrative. This makes for a fun book to read, and Grieder’s a talented writer.

We are left short of ‘proof’ that Texas has something to offer distinctive from other states, other than Texan’s belief in their own exceptionalism.

Please see related posts:

[1] Is waterboarding an appropriate metaphor here? Or is that too much?

[2] Here’s one for a local Caterpillar manufacturer last week. This one for a solar manufacturer was a doozy.

[3] As in this one, in which the City put money into a local private equity incubator, and this recent one, in which the City bought equity in a startup medical device maker, in return for it relocating to San Antonio. I hate this.

Post read (1773) times.