In honor of Leap Day, I’m writing today about something in the energy markets that shouldn’t exist. Or maybe it should exist only once every four Earth-revolutions around the sun.

In honor of Leap Day, I’m writing today about something in the energy markets that shouldn’t exist. Or maybe it should exist only once every four Earth-revolutions around the sun.

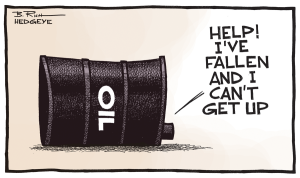

The oil price crash – we’re at 13-year lows in the average price of a barrel of oil this month – creates chaos for oil-company investors. That chaos in turn causes weird contradictory signals between the stocks and bonds of some oil companies. In order to illustrate this oddity, let me first introduce two of “Mike’s Newtonian Fundamental Principles of Finance.”

Efficient markets

Principle #1 – Markets are efficient.

Like, if I see a $100 bill lying on a city street, I’ll know that it’s not real, because how could it be? If it were a real bill, I know somebody would have picked it up by now, right?

Similarly, when in doubt, I try to never assume markets are stupid. I assume instead that I am the stupid one. Or, that what I observe isn’t real.

Principal #1 matters because right now, stock market prices for some public oil companies seem really stupid to me. I’ll name a few of these companies below, but first…

Bond people v stock people

Principle #2: Bond markets always understand what’s going on better than stock markets. Bond markets are better at math. Really it’s true, just ask anyone in the bond markets. Admittedly, I developed this prejudice during my experience as a bond markets guy, but still.

Principle #2 matters because the bond market is saying completely different things from the stock market when it comes to some public oil companies.

When distress happens

One more market-instructional comment, before getting into the present weirdness of specific oil company stocks: We typically think of earning money from bonds by capturing the ‘yield’ on an investment. Investors earn this ‘yield’ on their money from a combination of the bond’s principal and interest payments, made over time.

When a company become financially distressed, however, markets begin to value its bonds not for the yield from future payments on the bond (because the company might stop paying) but rather for the ‘liquidation value’ of the company. When the market begins to believe the company can’t make bond payments, it just looks to ‘how much would this physical stuff owned by the company be worth in a fire-sale out of a proverbial garage?’

Also, when a company can’t pay its bonds, holders of stocks should generally assume – there are exceptions, but still, work with me here – they will be wiped out. The shares go to zero in bankruptcy or liquidation

Oil company weirdness

If you want to see a weird phenomenon that shouldn’t exist, check out stock values of companies like WPX Energy (WPX), Carrizo Oil and Gas (CRZO), and Laredo Petroleum (LPI). According to the stock market[1] these are all ‘worth’ over a billion dollars in market capitalization, based on their share prices. (Market capitalization is share price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding, but you already knew that).

According to their bond markets, however, they are all possibly headed for liquidation or bankruptcy. Oil and gas brokerage firm GMP reports recent bond quotes recently for these three companies at 43, 63, and 59, respectively. Typical bond prices for healthy companies start and end around 100 cents on the dollar, but generally fluctuate between 80 and 120 cents on the dollar over the life of a bond. The math is a bit complicated, but as a general rule, the further prices fall below 100 the more likely the bond market values the company for it’s “liquidation” value, rather than it’s yield as a viable company making timely bond payments.

With these oil company bonds in the 40-60 range, the bond market right now says there’s a good chance these companies go into bankruptcy or liquidation in the short to medium run. The stock market meanwhile says there are more than a billion reasons to own their shares. It’s a puzzle.[2]

Since mid-2014, when the price of oil began dropping, oil companies have scrambled to survive. Many have been in distress for more than a year. [LINK: http://www.houstonchronicle.com/about/article/Credit-challenged-drillers-draw-on-creative-6056993.php]

With these three companies’ bonds ‘yielding’ around 20%, the bond market looks to liquidation value, and says ‘this market is closed.’

And yet, many of these companies have raised money in the stock market in the past year.

Laredo Petroleum raised $650 million in a stock sale in March 2015, back when shares were valued at twice what they are worth now.

In July 2015, WPX Energy raised $653 million in a combination of stock and convertibles (debt that can be converted into shares) although again, shares were worth twice then what they are now.

Carrizo sold shares most recently – $244 million worth – in October 2015. Those shares have also lost about half their value since then.

Here’s the problem in a nutshell. With the bond market saying these companies will likely be liquidated, I just don’t get how the stock market says they’re worth over a billion dollars.

While markets are undoubtedly efficient and you should question them at your peril (Principle #1), either the bond market is underpricing these companies or the stock market is overpricing them. Not being an oil market expert, I don’t know which market is right.

But because of Principle #2, I have my suspicions.

Please see related posts:

Beward people talking their book – including the oil market folks

[1] Note: these three companies are still all worth north of a Billion as I’m writing it, (last checked February 24th) but that can obviously change. Should check again on Friday before running this column to see if that’s all still true.

[2] At the risk of heading off on a tangent, other publically traded companies sometimes exhibit this strange behavior of probable-worthlessness combined with billion-dollar public share valuations. The former mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – in conservatorship since the 2008 crisis – still boast similar market caps of close to a billion dollars. But in their case they have advantages the oil companies do not, such as:

1) Hundreds of billions in profit in the last five years, sent to the US Government as owner/conservator.

2) Decades of lobbying to Washington insiders (It’s good to have friends in high places!)

3) Ownership by the world’s most powerful hedge funds, who are simultaneously lobbying for the companies and suing to wrestle ownership back from the US Treasury. The mortgage giants are special cases that these little oil companies can’t match.

Post read (205) times.