In June 2023 I featured a real estate investor who had made the bull case for Texas that it enjoyed unusual tailwinds as a diversified economy with low costs and a business-friendly government.

Ten years ago Hearst Newspapers columnist Erica Grieder wrote a whole book with this thesis Big, Hot, Cheap, and Right: What America Can Learn From The Strange Genius of Texas.

If you agree with this perspective, you now have a way to express this bet with your own money through a single exchange-traded fund, or ETF.

The central thesis of the new ETF (ticker TXS) launched in July 2023 by sponsor Texas Capital Bank, is that “companies headquartered in Texas enjoy certain economic, regulatory, taxation, workforce and other benefits relative to companies headquartered in other states,” according to the prospectus.

Ed Rosenberg, Managing Director for ETFs and funds management at Texas Capital Bank put it to me this way: ““The Texas economy is growing faster than the rest of the country. You have a lot of companies moving here, for obvious business reasons. It’s cheaper, and it has a better tax situation. There is a lot of young talent. A lot of people want to live in the state. Texas has more Fortune 500 companies headquartered here than any other state.”

You can imagine this kind of message appeals to state leadership. In fact Governor Abbott has been doing yeoman’s work to tout this new ETF, and even celebrated it by ringing the closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange on September 29th, along with executives from Texas Capital Bank.

How should we evaluate this fund on its merits?

In order of priority, in evaluating a potential investment mutual fund or ETF, I would look at effective diversification within its theme, fund cost, tax-sensitivity and lastly, a track record of returns.

Diversification

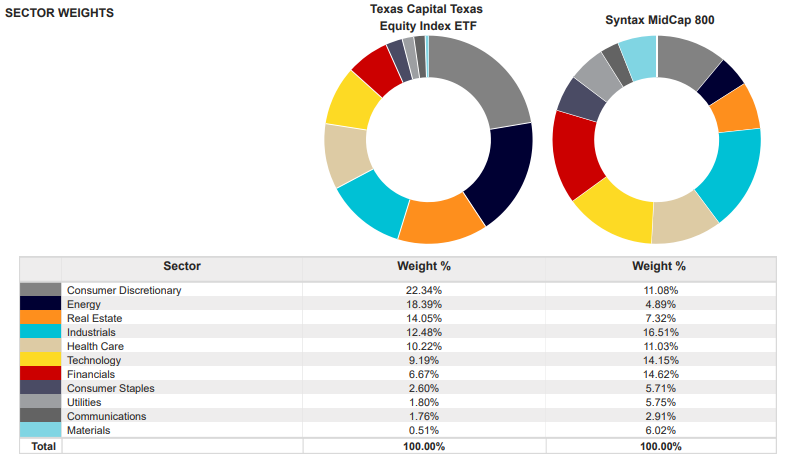

The managers of TXS have paid outside data firm Syntax to create a unique index with two layers to it. The first layer is built on data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, which measures the GDP of Texas to figure out which industries contribute to the economy, in what proportions.

Syntax then seeks to match the industry weightings of the fund to the relative influence of different sectors on the Texas economy. The managers identified eleven separate industries that make up the Texas economy. Energy is the largest component, but is still less than 25 percent of the index. Meanwhile consumer discretionary, industrials, and information technology make up 14.5, 12.7, and 11.5 percent of the Texas economy respectively, and therefore make up that much of the index on which TXS is built. From there, the index qualifies companies within each sector, and weights them according to market capitalization, which just means their size.

As of September 29th, the top ten largest holdings comprised 35 percent of the fund, including well-known Texas-based companies such as Tesla, Exxon, Charles Schwab and Waste Management. So there is some significant concentration with giant companies headquartered in Texas.

Further criteria for inclusion: Companies have to be headquartered in Texas, and meet liquidity and publicly-traded size characteristics. No penny stocks here, or closely held companies with a tiny “float,” of shares that barely trade. Overall the ETF owns more than 200 companies in eleven separate GDP-weighted industries, so certainly passes the diversification test.

Something that the fund by definition does not offer is geographic diversification, but rather the opposite, geographic concentration. An investor would need to achieve geographic diversification with some other vehicle.

Style

One thing we can say about TXS, relative to the mid-cap index against which it is judged, is that the Texas companies in the index overall skew more toward a “value” orientation rather than a “growth” orientation. This is reflected in the dividend yield (higher than the index), in the price/earnings ratio (lower than the index) and the fact that energy rather than technology is the largest industry within the fund. That doesn’t predict returns in the future, but it is a set of characteristics that would help an investor or investment advisor figure out how TXS could interact with other investments within a larger portfolio.

Costs

TXS charges a 0.49% management fee. Management fees for mutual funds and ETFs have come down dramatically over the past two decades. If a standard mutual fund would have cost around 1 percent in fees in 1993 or 2003, the competition from low-cost index funds has made a 1 percent mutual fund or ETF an outlier today. Many passive ETFs charge 0.03 percent or 0.1 percent these days, one-thirtieth or one-tenth of what might have been standard two decades ago. To choose a higher cost ETF in 2023 is to make the implied bet that the higher-cost fund will consistently outperform its benchmark, every year. That rarely happens, so it’s rarely worth doing. TXS at one-half of one percent is somewhat expensive for an ETF. You’d expect it to earn half of one percent higher than comparable funds every year to justify the costs.

I’d grade TXS with a solid B in terms of cost. It’s not 1 percent pricey, but there are many cheaper ETFs in the marketplace.

Tax

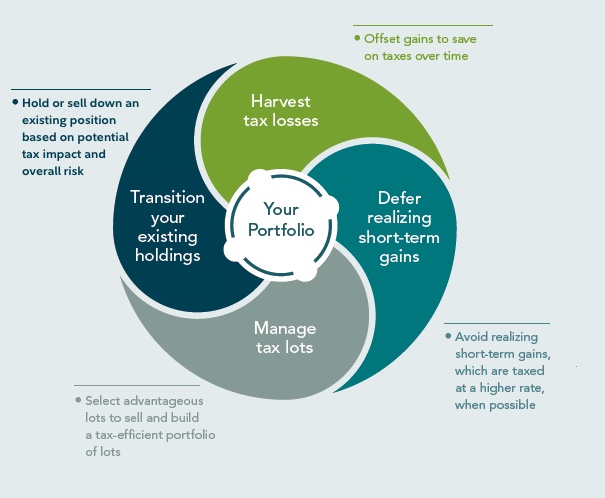

Tax sensitivity matters only for funds held outside of a tax-deferred retirement account. A “tax-sensitive” fund refers to the idea that high-turnover funds may generate capital gains tax liability throughout the year that a low-turnover fund does not. In general, tax sensitivity would favor passively-managed investments over actively-managed investments, and a long-term buy-and-hold approach instead of a short-term tactical approach.

TXS describes itself as passively managed, so should end up fine on a tax sensitivity measurement. The portfolio manager also has discretion to manage securities to minimize taxes, according to Rosenberg.

Expected Returns

TXS first became available in July 2023, so past performance measurement in October 2023 is meaningless. I mention this mostly to make the point that short-term returns should be a pretty low priority when picking this, or any other, fund.

A rookie mistake in purchasing ETFs and mutual funds is to choose the best performing recent fund over the past 1 or 3, or even 5 years. Not only is that time horizon too short to give meaningful information, but that approach puts the investor at risk of buying hot funds, just as the market or investment fashion takes a turn in a different direction.

Any outperformance of the fund versus its benchmark may be attributed to the initial thesis of the fund over the longest period of time. Or, it could be attributable to other factors that will be mostly understood in retrospect. In any case, judging returns of a fund in a time period less than 10 years is to risk conflating noise and signal.

We might have some useful data 10 years from now to judge whether the “Texas Thesis” of 2023 was a good one or not. But we definitely don’t have enough data now to make that judgment. So investing in TXS can only be based on a hunch and a gamble. I’m not knocking gambles. Lots of investing is done this way. I just think it’s useful to acknowledge that we’re doing that.

I do not personally own TXS in my portfolio, at least for now. (Your daily reminder: super-low cost, super-diversified equity index funds all the way, baby!). For similar life-philosophy and personality reasons I also don’t drive a King Ranch Ford F-150. For investors who don’t mind paying a little extra and who believe in the exceptionalism of Texas, Texas Capital Bank has invented a clever way to put your money where your cowboy boots are.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post:

Book Review: Big Hot Cheap and Right, by Erica Grieder

Post read (29) times.