Once upon a time – a little over a year ago – I helped a friend start an employee retirement program for her business, and that made both her and me feel very good. Building the long-term financial health of employees – in a tax-advantaged way – has to be one of the most rewarding activities a greedy capitalist can do.

Once upon a time – a little over a year ago – I helped a friend start an employee retirement program for her business, and that made both her and me feel very good. Building the long-term financial health of employees – in a tax-advantaged way – has to be one of the most rewarding activities a greedy capitalist can do.

More recently, one of those employees checked with me about market volatility during the first part of the year. I happened to be stopping by their office. She happened to be worried about the fact that despite making contributions over the previous 6 months, her account hadn’t grown at all. With the market dropping so much, and so often, she wondered, shouldn’t she maybe stop her contributions for a bit? Just, you know, until the market settled down. I don’t think she wanted to sell her holdings, just cease the payroll contributions. For a bit.

I waited theatrically until my jaw fully bounced from the concrete before closing it.

“What?!” I stage-whisper-shouted, so that everyone else would hear.

My reaction gave her all the answer she needed about what I thought of her idea. Hopefully I looked so alarmed that all her colleagues took note and put away any thoughts of market-timing their tax-advantaged retirement account contributions.

Still, her question deserves a more fleshed-out response than my mock shock.

A contrarian truth

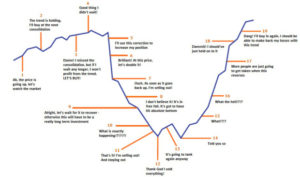

Her logic came from a perfectly sound interpretation of the well-known investing cliché ‘Buy low, sell high.’ The market is going down, she’s thinking, so let me wait until the bottom to resume buying, at the lows.

I recently read a very good case for why ‘Buy low sell high’ is “the worst financial advice of all time.” As you may already know, I’ve got a soft spot for crazy-sounding contrarian opinions that reveal an underlying wisdom.

Why should we not try to “buy low and sell high?”

I mean, yes of course, there is mathematical logic to purchasing with the smallest number of dollars and selling with the largest number of dollars. We end up with more dollars. But that increasing-dollars thing is not in fact what generally happens when we attempt to “buy low and sell high.”

Adopting the idea that we are responsible for picking the lows and highs logically leads to trying to time the market. We might see the market value of our investments drop and think it’s better to sell before it drops more. Or we might stop contributing to our retirement account, until we’ve ‘hit the bottom.’ Or, we could attempt to load up on some investment because it dropped 25 percent, or whatever.

In fact, much of the financial-infotainment-industrial-complex is built on this false premise that we should attempt to ‘buy low and sell high.’ The attempt to figure out highs and lows in a peripatetic market seemingly justifies tuning in to the trash fire that comprises most of television’s investment programming.

Bad Results

What happens when you falsely believe it’s your job to “buy low and sell high?” A whole bunch of bad things happen, such as:

- You trade more often than you should, incurring higher transaction costs than necessary.

- You trade more often than you should, incurring punishing tax rates.

- You buy things because they’ve gone down in price, even though they can continue to go down much further.

- You sell things that have gone up in price, even though they may be worth far more in the future than they are today.

- You leave money for too long in low-risk/low-return assets like bonds or cash or money markets waiting for the right low-point when you can buy, forgetting that that low point only happens when the financial apocalypse seems upon us, and it would seem madness to invest in risky markets then.

Instead, Do Nothing

My friend the anxious employee – hopefully – will stop paying attention to the value of her investment account any more often than, say, once a year. She’s 30-years old right now, which means she will likely have this money locked away in the market for 30 to 50 more years. A 10 percent drop, a 20 percent drop – heck a 35 percent drop – in the value of her account means nothing compared to what she will earn in the long run if she stays the course, investing they way she should.

At a 6 percent return for thirty years, she will make nearly 6 times her current money. At a 6 percent return for fifty years, she will make more than 18 times her money. That 6 percent return doesn’t come in the form of steadiness, but rather stomach-churning downdrafts and breathless upswings, and everything in between. Big temptations, each one, to try to buy low and sell high.

At a 6 percent return for thirty years, she will make nearly 6 times her current money. At a 6 percent return for fifty years, she will make more than 18 times her money. That 6 percent return doesn’t come in the form of steadiness, but rather stomach-churning downdrafts and breathless upswings, and everything in between. Big temptations, each one, to try to buy low and sell high.

Earning multiples on your retirement money will work best if she resists the urge to “buy low and sell high,” or any other timing-based behaviors, like halting contributions when the market gets volatile.

Instead of “Buy low and sell high,” a better mantra would be “automate retirement contributions and then: do nothing.”

See related post:

Post read (611) times.