Picture that scary in-between financial moment, a kind of knife-edge living, when you have too much high-interest debt to pay off in any reasonable amount of time, but not so much debt that bankruptcy is necessary or inevitable. What do you do?

A friend of mine, who would like to be known just as D, received an offer in the mail from Americor Financial Services, promising a new $27,000 line of credit.

D pays all his debt on time, but it’s expensive. He anticipates additional expenditures in the months to come. D would like more available credit. D called Americor to learn more about that line. After offering up details over the phone on his financial situation, including how much debt he currently pays on, the representative described a plan. Begin paying Americor monthly, approximately $500 less than he currently pays, and cease paying on the rest of his high-interest credit cards.

![]() After 4 to 6 months, the representative told him, Americor will be able to negotiate from a position of strength with his banks. The representative practically guaranteed that the banks would accept a negotiated settlement for 50 percent of what D owed.

After 4 to 6 months, the representative told him, Americor will be able to negotiate from a position of strength with his banks. The representative practically guaranteed that the banks would accept a negotiated settlement for 50 percent of what D owed.

Perhaps the most intriguing part of the Americor representative’s pitch to my friend is that Americor promised that his credit rating – which is currently strong — would only temporarily dip, for about six months. After that, it would bounce back quickly. In addition, the debts would be reported to the credit bureaus as “paid in full,” even if reduced to 50 cents on the dollar. I call BS on that part.

What about that original $27,000 line of credit promised in the mailing, my friend D asked the representative? That line, it turns out, is only available approximately 16 months after enrolling in Americor’s program, or once his outstanding debt has been reduced by 50 percent. The line of credit would cost 18 percent annually. The Americor representative assured D his credit would be good enough to obtain a better rate elsewhere, if he wanted to, at something like 8 percent.

That of course, would depend on having great credit 16 months later. Which, again, I doubt.

D told me,

“No equivocating, they promised me that the old creditors would be happy and eager to extend me new credit at the end of the process.”

Wouldn’t his score go down, D asked Americor, repeatedly? D told me, “He said it would just go down in the beginning, but that sometimes you have to take one step back before taking two steps forward.”

The Americor representative told him “people do this all the time.”

In fact, much of this pitch sounded like BS to me. To give Americor the benefit of the doubt, banks do settle for less than the full amount owed on debts that have gone delinquent, especially perhaps over 90 days. But the claims about a quick bounce back in credit score did not pass the smell test.

I reached Dwight Flenniken III, Chief Marketing Officer for Americor, on the phone. I presented to him my two main doubts. First, not paying debts for 90 days would absolutely wreck my friend’s strong credit. Second, his credit bouncing back in a year and a half just didn’t make any sense.

Credit card companies care a tremendous amount about both timely payments and full payments. They distinguish between 30-, 60-, and 90-days late on payments as increasingly severe problems. Any 90-days late payment has a lasting effect on your score. Accounts in collections and accounts not paid in full stay as negative marks on your credit for years.

Talking with Flenniken cleared up my confusion, at least as it would apply to my friend D.

The first reason is that Americor’s typical client is in a lot worse shape, credit-wise, than my friend.

“People don’t come to us until their credit is wrecked. Most of our consumers have between a 540 and 600 FICO,”

Flenniken clarified. Starting from a low FICO, Flenniken and I both agreed, a downward dip isn’t very consequential.

Since D’s credit is in the high 600s, close to Prime, his score would fall a lot further than the typical Americor client. I think the original representative painted an overly positive picture of the consequences for my friend, in terms of “one step back and then two steps forward.” Flenniken agreed D might have better options than Americor.

The second factor involves a little game – my word, not Flenniken’s – that Americor plays with the credit bureaus. They begin by reporting a new open line of credit with the debtor within a few months of enrollment in their program. A client like my friend, however, would not be able to actually access the line of credit until lots of conditions had been met, often not until that 16 month mark.

The second factor involves a little game – my word, not Flenniken’s – that Americor plays with the credit bureaus. They begin by reporting a new open line of credit with the debtor within a few months of enrollment in their program. A client like my friend, however, would not be able to actually access the line of credit until lots of conditions had been met, often not until that 16 month mark.

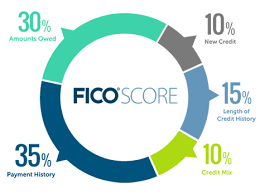

The thing you have to know about this trick is that 30 percent of what makes up a FICO score is what’s known as “credit utilization,” meaning the portion of your lines of credit that you’ve drawn upon.

A new $27,000 line reported on my friend’s credit from Americor – that he can’t actually access for another year – would act as a significant buoy to his credit score through improving his “credit utilization” score. That buoy could partially counterbalance the effect of delinquencies, especially for someone starting with very low credit. The fact that this new credit line is in theory only – again, not accessible for over a year – is why I consider this a bit of credit-scoring legerdemain 1 that Americor plays. They’ve kind of hacked the FICO score.

On the knife’s edge, there’s a place for struggling through, sucking it up, and knocking out one’s debts the slow, hard way. There’s also a place for a fresh start through bankruptcy, or hiring a debtor’s attorney to negotiate for you, or even working with a debt negotiation company like Americor. A debt settlement company over-promising an “easy way” out of too much debt without hurting your credit, however, is just setting you up for disappointment.

D tells me he will not be going forward with Americor Financial Services.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle

Please see related post:

The Power of a Debtor’s Attorney in TX

Post read (248) times.

- Dare I say, ‘prestidigitation?’ ↩