Ok, so it’s no secret I’m pretty sweet on SIGTARP, the Norse God of Financial Accountability.

Ok, so it’s no secret I’m pretty sweet on SIGTARP, the Norse God of Financial Accountability.

There’s the pleasure of calling a fellow US Treasury colleague a liar.

There’s the feistiness of a government official pointing out that through our failure to rein in TBTF banks, we’ve laid the groundwork for the next crisis

There’s the carefully balanced review of the Citigroup Bailout.

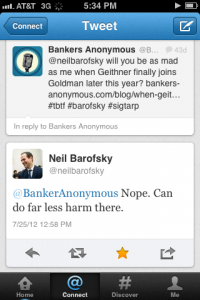

Frankly there’s the plain old fun of SIGTARP himself, Neil Barofsky, responding during his book tour[1] to my tweet about Geithner, unconcerned that Geithner would jump to Goldman, Sachs, because at least at GS he’d do less harm than as Treasury Secretary!

But I digress. There’s a good deal of valuable information in SIGTARP reports, and in this installment I thought I’d highlight a few things we can learn about small and medium size banks. I’m sad to say that four years after the Credit Crunch, many small and medium size banks are doing terribly.

US government regulators NEVER tell you which banks are in distress.[2] But SIGTARP consistently goes where other regulators dare not tread.[3] Read the full report to find out which small banks will go under next, probably by 2013, or simply go to the list of banks which have missed dividend payments.

On missing Dividend payments owed to Treasury for TARP money

The stated reason for TARP was to ensure that TBTF banks did not bring the entire financial system to a grinding halt when taken over by the FDIC or placed in receivership. For less clear-cut reasons[4] however, Treasury also offered small and medium size banks a chance to take advantage of the fast-track route to recapitalization via government investment.

As it turns out, and despite explicitly forbidding this[5], the TARP money extended a lifeline to small and medium size banks that have failed to thrive following the Great Credit Crunch. A few hundred of these banks have either succumbed to failure or have missed so many dividend payments to the Treasury that survival seems doubtful.

SIGTARP reports list not only those banks which have outright failed or those where the government has lost money, but also those banks that have missed dividend payments to the Treasury and the number of those payments as well. The missed dividend signals the banks that are probably too far gone to survive.

Wondering if your local TARP-bailout bank is in good shape? You can check for it in the SIGTARP report HERE.

To save you some time scrolling through the SIGTARP report, you can look on the following pages for:

Pp 98-102: 162 Banks that have missed one dividend or many dividends.

Pp 102-103: 41 Banks where the US Treasury has realized a loss through its TARP investment.

Pp 110-117: 99 Banks that have failed, gone bankrupt, or had their US Treasury investment forcibly restructured.

On troubled Community Banks that still owe TARP money

One measure of recovery from the Great Credit Crunch would be the strength and stability of banks in the United States. And, unfortunately, a great number of small community banks, we learn from SIGTARP, are really still sucking wind.

While 90% of the original TARP money[6] from late 2008 has been repaid from all of the TBTF banks (except Regions Bank), small and medium size banks have been much slower to repay.

As of the latest Congressional report, approximately 400 small and medium size banks have yet to pay back TARP funds. Even that group of 400 TARP banks overstates smaller banks’ ability to repay, since an additional 137 banks swapped TARP funds for a program custom-designed to let them off the TARP hook, through a financing called SBLF.

What are the implications for the future of small banks unable to repay TARP?

400 banks account for approximately 5% of banking institutions in the country, not a huge portion of the total. In a strictly macroeconomic sense, it is systemically irrelevant whether these banks live or die in the years to come. A case can even be made that fewer banks in the United States would be just fine.

From a taxpayer perspective the $20 Billion value in small bank preferred shares and warrants represents less than the US Treasury risked with individual banks such as Citigroup and Bank of America in the early days of the crisis.

On the other hand, comparing small bank failure to household financial failure shows the locally devastating effect if they implode financially. That is to say, it matters to those banks and their communities if they fail. Not only that, we can assume, not unreasonably, that failing banks will be concentrated in depressed regions of the country, exacerbating access to credit for small businesses and real estate developers in precisely those areas which can least sustain losses.[7]

The SIGTARP report provides evidence, if you read between the lines, that a great number of these smaller 400 TARP recipients are on life-support, and many will not make it out of the intensive care unit.

Congress passed the Small Business Lending Fund (SBLF)[8] nominally to provide more credit for small business, but in reality to allow medium and small banks to exit TARP and roll into a less restrictive government program.[9] One hundred thirty-seven banks qualified for Treasury funding under SBLF by proving their likelihood of increasing their loan portfolio to small businesses – and exited TARP shortly thereafter. Those who could exit TARP at that time, did – the rest could not.

Furthermore, executive compensation restrictions make it unlikely that any bank still owing TARP money has a profitable and sustainable banking franchise. If they could have paid it back, they would have by now.

The 162 Banks Most Likely to Fail

As of the July 2012 report, one hundred sixty two, or almost half of the remaining 400 TARP banks, have missed dividends (currently with a 5% coupon rate) on the preferred shares owed to Treasury. By law, the dividend rates jump to 9% on these bank preferred securities beginning in 2013. Payments of 9% on their capital is an exorbitant rate for banks to pay when the costs of funds in the money markets for healthy banks remain below 2%.

In sum, the picture is grim for remaining small and medium TARP banks, but the financial system and ordinary taxpayers will not suffer extraordinary losses. To badly hit communities, however, more pain awaits, probably in the second half of 2013 when 9% dividends deal the fatal blow to weak banks.

Also see:

In Praise of SIGTARP Part I, “Truth in Government”

SIGTARP Part III – “The Citigroup Bailout”

and SIGTARP V – The AIG Bailout

[2] There’s a good public policy reason for this. Exposing a weak bank publically may create a self-fulfilling prophesy of weakness, as depositors and customers leave the zombie bank for its stronger competitors.

[3] Which is why it’s kind of an illicit thrill to see struggling banks publicly outed this way. I know, I’m weird.

[4] One strongly implied reason at the beginning of TARP was the ‘safety in numbers’ idea. That is, if many banks took TARP funds at the same time it would remove the stink of government intervention from the actual targets, the TBTF banks on the financial precipice. Another reason is probably the sway of small and medium banks with their Congressional representatives. One reason that makes less sense is the systemic value of small and medium banks.

[5] TARP funds were supposed to be only available to Qualifying Financial Institutions (QFIs.) But the definition of a QFI included the mandate that they be “healthy, viable institutions.” We know with hindsight that at least both Citigroup and Bank of America would have failed to qualify for this designation had “healthy, viable” been a truly disqualifying condition. But we now also know hundreds of small banks failed that test as well.

[6] In this posting, by “TARP funds” I really mean to refer to the Capital Purchase Program (CPP) by which Treasury bought preferred shares and warrants in 707 banks, including the largest 17 TBTF banks. Technically “TARP funds” could include a wide variety of other investment programs authorized under TARP, but I’d rather use the acronym TARP than CPP, since it is better known.

[7] See this interesting site with stats and maps of bank failures.

[8] In September 2010

[9] The initial dividend rate of 5% matches the TARP dividend rate of 5%, but crucially SBLF funding does not carry restrictions on executive compensation. Much better, Smithers.

Post read (3510) times.