In 2020, the best living writer on personal finance published his first book. (No, I don’t mean me, silly. You are just too kind, stop it, I’m blushing.)

Morgan Housel wrote The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness and, of course, I had pre-ordered it from Amazon and yeah, you should read it.

If you’ve already read dozens of personal finance books (I have!) then I’m not saying you must read this one. But you will be entertained, and you will finish it in less than a day. If you haven’t read many personal finance books before, then this is a really good place to start. And if you haven’t specifically read Morgan Housel before then you are in for a treat.

Each chapter tackles a key aspect of wealth-building. I particularly enjoyed his chapters on wealth, risk-aversion, and narrative bias.

Wealth is not achieved by owning a bunch of expensive stuff. The fast cars, the big houses, the fancy electronics. We often believe people who have those things must be wealthy. Maybe they are, or maybe they just have an appetite for debt. Without checking their bank statements, we usually don’t know. Wealth, Housel argues – I heartily agree – is better measured in terms of freedom. Freedom to spend your day just as you choose, wherever you want, with whomever you want.

Importantly, a pile of money in the bank can be quite helpful in obtaining that freedom. But equally true, vastly different amounts of money enables emancipation from obligation, depending on the size of one’s wants.

To the extent the expensive stuff actually diminishes your available pile of money necessary for freedom from obligation, it’s not a stretch to understand that the car, house, and electronics may actually result in less wealth, not more. Wealth, Housel reminds us, is achieved through what you don’t buy. Readers familiar with the classic finance book The Millionaire Next Door will recognize this whole thought process.

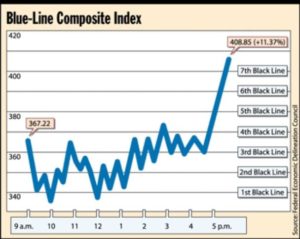

Here’s another great point Housel makes. In investing, the price for good returns is often volatility and uncertainty. If you can’t handle either volatility or uncertainty, you can’t afford to be in assets that provide a good return. Most people, it turns out, can’t really pay that price. In behavioral finance, we talk about the related idea of asymmetric risk aversion. This means we suffer from losses much more acutely than we enjoy gains. We focus on the bad and have trouble tracking the good. A pessimistic worldview holds our attention and feels “realistic” while an optimistic worldview feels “unserious” or “unreliable.” Newspapers know this, as captured by the cliche “If it bleeds, it leads.”

Nobel-prize winner Daniel Kahneman suggests this focus on the negative over the positive had evolutionary roots, “This asymmetry between the power of positive and negative expectations or experiences has an evolutionary history. Organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce.”

Unfortunately, this explains why most people can’t handle the advice to “buy and hold” stocks for multiple decades, despite overwhelming evidence that this is the right way to go.

Like other accessible finance writers, Housel relies on narrative and anecdotes to illustrate his timeless lessons. You will recognize familiar heroes and villains from these stories of wealth and greed, such as Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, Bernie Madoff and Rajat Gupta.

As an improvement on the familiar, Housel devotes a chapter to how narrative can deceive as well as illuminate, when it comes to investing. Behavioral finance teaches us that in the face of uncertainty – and investing is always uncertain – our brains tend to tell us stories that make us feel less uncertain, even when that’s unwarranted. Once we become attached to a certain story – this company always beats its earnings, that industry is crumbling, this entrepreneur achieves engineering wizardry on a regular basis – we disregard the data that doesn’t reinforce our pre-set narrative. We do this in our relationships, in our personal identity, and in our politics. Housel warns that it can be an expensive tendency to stick to the same preconceived narrative in investing.

One of the most pleasing parts of finishing The Psychology of Money, to me, is that Housel eventually says in the penultimate chapter what he does with his own money and investment portfolio.

If you always wondered what a careful money knower does with his own money, you may be similarly interested in that question and his answer.

Readers of my stuff over the years will already know how I answer that question. But if you don’t yet know, I am pleased to report that Housel does exactly what I think the right answer is. So you can read his, and my, answer for yourself, in Chapter 20.

But of course we should consider the implicit possibility, which I now make explicit, that maybe I appreciate and celebrate Housel because his narrative about money and investing closely matches my own narrative about money and investing? Perhaps I have fallen prey to the very same confirmation bias that behavioral finance warns us against? Gosh, it’s all so meta.

Addendum

Quick addendum about the best living finance writers. In 2020, The New York Times wrote up a feature on the second-best living finance writer, Matt Levine

Levine writes a column for Bloomberg News called “Money Stuff,” available for free as a daily email. Everyone should subscribe.

He is intellectual, hilarious, and produces in-depth, annotated daily explainers about Wall Street from a guy who used to work on Wall Street, respects the game, revels in the complexity, but who also sees the irony and humor in it all. Levine is like me, but five times as good.

Thankfully the competition is still open for third-best living writer on finance. I’m reserving a spot on my mantle for the bronze medal. So, please, get all your ballots in on time. Is that not what this election chatter I’ve been hearing is all about?

Please see related posts:

Please see all Bankers Anonymous book reviews

Post read (151) times.

e United States. The book also might seem to serve as an updated guide for the rest of us to make sense of the mess of race relations in the United States.

e United States. The book also might seem to serve as an updated guide for the rest of us to make sense of the mess of race relations in the United States.