Podcast: Play in new window | Download

In this interview Bryant talks about the difficulty of employing oilfield workers, who often look for trouble.

In this interview Bryant talks about the difficulty of employing oilfield workers, who often look for trouble.

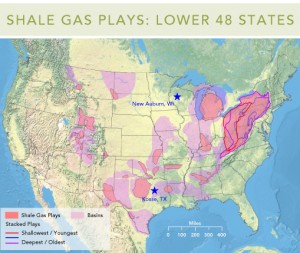

Bryant: Hello, my name is Bryant, and I presently work for a company that develops and operates frac-sand silo terminals in the Eagle-Ford shale.

Bryant and I spoke about his views working on the fracking world in an earlier podcast but we also spoke extensively about the impact of the Natural Gas Revolution on jobs in South Texas. The first point is that there are a ton of jobs created. The second is that it turns out the work-force can be pretty rough.

Bryant: The extracting of natural gas from the earth does create a lot of jobs, which is something that obviously this country is starving for at this time. You know people tell me, “I don’t want to work as a rig hand.” No, I’m talking complete cities are developing because of this stuff. An oilfield comes in first: you need restaurants, you need hotels, you need rent-a-cars. You start to develop quite a bit of economy — you have an economy wherever this stuff really starts to kick off, and I think that’s good. You need welders. You start to then develop actual skilled workers.

Michael: I went on the site of this company and everything was provided seemingly by something else. There were the Schlumberger signs, the Halliburton signs, the guys guarding the entrance to the ranch that they were drilling on. There was the catering guys. This is being done in an area where it’s basically raw ranchland for a hundred years, and they have to basically import services for everything. It was kind of amazing.

Bryant: Everything, generators, electricians — any time I have an issue with my silos and I need an electrician, it’s not easy. If you need a skilled worker in some of these areas they’re very difficult to come by. Like I said, labor, that’s why the Eagle Ford is so attractive. You’ve got San Antonio, Houston, you’ve got major cities that people are leaving and flocking to these smaller towns, really in the middle of nowhere, and providing all the services needed.

This stuff, fracking, it employs a lot of people that may not have education. It employs a lot of people that have a lot of mouths to feed, that may not have really the education to go and get an office job. I think that’s really important for the world. A lot of people don’t have the opportunities to get the job they really desire. They just need a paycheck. This really helps. I would hate to see all these towns I deal with, all those people not working. We’d have a serious problem on our hands. I mean by just violence, and upset people.

Michael: You and I talked about your earlier job in the Eagle Ford that was with a buddy of yours…Can you just describe for me the part about what it’s like to manage a bunch of guys in an oilfield work environment, and how different it was from what you’d expected, or where you come from?

Bryant: It’s tough. It’s probably the hardest part of my job still to this day. I came from working before I moved to Texas to work in this industry I worked for the publishing industry in New York City for five years. I was constantly surrounded by people that probably like to read a lot of books and keep up with current events, etc. I came into an industry where not a lot of the workers on the ground have college educations.

Michael: What about high-school educations?

Bryant: Not a lot of them have high-school education as well, so it’s very difficult, at least for me just to bridge that gap between office work and someone that’s been driving a truck for their whole lives, and who don’t really understand why there are procedures that can’t be broken, and why there are rules that need to be maintained. They just seem to care about it’s my truck, I want my money, and that’s it or I don’t want to work today because I didn’t get a good night’s sleep last night.

So, it is very difficult. I hate to use the word unruly, but you come across a lot of people that they sometimes don’t really care as much as you’d like them to. Now it also is very difficult in that a lot of these towns you get fired or you quit from one place, you just walk across the street and they’ll hire you immediately to do the same thing you were just doing. There’s such a need for drivers and people with experience. Workers know this. So, they know if they don’t show up because they went out and they blew their check and got drunk, and just didn’t wake up, and they come in two days later and you fire them, they’re just going to walk across the street and get fifteen, twenty dollars an hour doing the same exact thing for somebody else.

That environment is difficult. A lot of companies are trying to adapt, trying to have the medical insurance and 401(k), trying to maybe have a little signing bonus. You have to do things to keep good workers because it’s very competitive. But it is very difficult to manage people in the oilfields sometimes. They can be a little rough around the edges, but that’s why I think managing in this industry actually pays pretty well. It’s not an easy task.

Michael: I’m afraid you don’t have enough tattoos to be running this kind of crew.

Bryant: I definitely change my attitude a bit, depending on who I’m with. If I’m not in the field, you kind of change a little bit. You try to blend in a little more and probably in the vocabulary. I use a lot more oilfield jargon than when I’m probably doing a sales call or some kind of meeting at a corporate level. So again, I think that’s what makes it a fun job for me. You’re constantly a chameleon and you’re in between two different worlds all the time.

A lot of these guys can be pretty irresponsible. They make really good money, so a lot of times they come from places where they don’t make — they come from poorer backgrounds and all of a sudden you’re making twenty, twenty-five bucks an hour, you’re clocking twenty, thirty hours of OT because it is twenty-four hour drilling. This stuff never stops, so you’re making a lot of money. You probably didn’t learn money management much and kind of start getting into trouble.

Michael: Is there trouble to be had in South Texas?

Bryant: Oh yeah, there’s always trouble. I’ve never actually been up to North Dakota. They say it’s like stepping onto the moon, it’s so barren. I do know people that have been up there and they said, “Honestly, you get to some of these places, and the only thing there is, is like a barbecue joint, a trailer park, and a prostitution house. That’s all you need is drinks, and money, and women, and these guys probably stay pretty happy for a while.” There is trouble. There is a lot of trouble.

I used to actually give out paychecks on Mondays instead of Fridays because workers tended not to show up on Saturday. They’d get their money on Friday, they’d go and get drunk, and I’d get a call maybe somebody was in jail, or somebody was drunk, and I really had to just change my rules. I said everyone gets paid on Monday. You don’t go out and get in as much trouble on a weekday. Yeah, there’s a lot of trouble.

Bryant and I spoke of the difficulty of managing the low-end of the labor market, but then he described the other end of the labor market, the scientists and engineers providing the brainpower for the shale play. As much as the story job-wise is mostly positive, I couldn’t help but think of the idea that we’re in the role of a 3rd world country…we provide the low-end cheap labor, and the rest of the world provides the brains.

Bryant: I’m going to tie this into politics a little bit, but you meet all these engineers for the big three: Halliburton, Schlumberger, and Baker, and not a lot of them are from the U.S. You meet a lot of them from India. You know, Asian and South American. It’s crazy. You actually sometimes walk into these offices and it’s like the United Nations. It’s people from all over the world, which is great, I’m all for it, but I think it shows that we are slipping more and more, like everyone has been saying, in our math skills, in our education, period. We have a great technology but we’re not really creating people or educating people to do it. We’re kind of letting it get away.

Michael: So, the high-end intellectual jobs, the engineering jobs, the people inventing this stuff or figuring it out are not necessarily trained here. They train somewhere else and then they get here.

Bryant: This is definitely the testing ground. The U.S. is where it’s happening, but a lot of those times it’s being created by an engineer that’s not from here. You’re getting people from other countries that are seeing an opportunity to come into the industry and make some money. The industry is eating them up. The industry has money to pay for the best, so they’re buying the best minds they can buy to make their work more efficient so they can make more money.

Please also listen to Part I: Fracking and Regrets

Post read (10434) times.