Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Note: I reviewed Gary Sernovitz’ book in September, and we did a phone interview back then, which I’ve now posted as an audio interview, Part I – on the big personalities in fracking. Part II – on environmental issues, will follow. I recommend listening to the audio version, but I’ve posted a transcript of our conversation as well.

Mike: Hi, my name is Mike, and I used to be a banker.

Gary: And I’m Gary. I guess I’m sort of still a banker, at least a private equity investor.

Mike: Perhaps more importantly, you’re also ‑‑ full name, Gary Sernovitz the author of, among other things, The Green and the Black: The Complete Story of the Shale Revolution, The Fight Over Fracking and the Future of Energy. Thanks for talking.

Gary: Thanks for having me.

Mike: As you know, I read and really enjoyed your book, and I reviewed it on my site. I just want to praise you for doing what I think is my favorite thing, which is taking a complex issue upon which nobody agrees, and everybody thinks the other side is complete fucking idiots, and saying no, we’re not all idiots. We could understand each other. So thank you for doing that. That’s really great.

Gary: Thanks for the praise and clearly, that is not the dominant mode of American discourse, as evidenced by the discussions heading into November.

Mike: Yeah, it’s really difficult to not see the other side as either morons or dupes or evil. And I would say if you just say the word “fracking” we’ve already introduced the idea the other side is one or all of those things. I appreciate you describing yourself as a New York liberal. And I described you as deep in enemy territory there for fracking, and yet you have to both answer for your profession, which is to be investors in energy and in oil and gas and fracking, but at the same time, be a thinking person.

I don’t know who’s more unattractive, oilmen or Wall Street guys, but every once in a while, I’ll say something mildly positive about a Wall Street guy in some column and people will write inevitably “You’re such a jerk talking about the banksters as if they’re not all evil.” Okay, sorry.

Gary: I manage to work for a private equity firm that invests in the oil and gas business to be the worst of both worlds.

Celebrities of Fracking – Aubrey McClendon

Mike: Some of the interesting parts about your book are combinations of celebrating capitalism, and ingenuity of the shale revolution, and incremental changes. And then part of that celebrating capitalism is celebrating some of the funny and interesting characters who made good off of the thing.

I’m interested in some of those. Some of them I’ve heard some of their names but don’t particularly know them, but I understand they’re rock stars of your industry. I’d love to chat about those if you don’t mind.

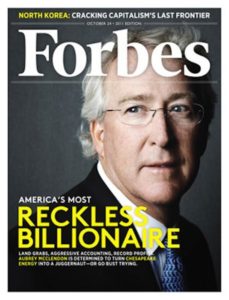

One, your favorite seems to be Aubrey McClendon who I guess died after you’d written the book. I don’t think you referenced his death, or maybe you do?

Gary: No, he died in what is not terribly clear ‑‑ whether it was self-inflicted or not, but drove about 80 miles an hour into a highway overpass the day after being indicted.1 Obviously, a lot of speculation on the timing of that.

Mike: Certainly looks suspicious, as a complete outsider.

Gary: The conclusions most people have drawn ‑‑ but I think there has been no official word from the investigation one way or the other. Not necessarily that there needs to be, but the funny thing about the book is there was an alternate book that was just sort of a straight biography of McClendon that kind of was impractical to write with my job and with need to write ‑ he’s backed by a firm in his later life that competes against my firm in terms of providing capital to oilmen. I ended up putting that to the side.

Mike: There’s a book worth or more of Aubrey McClendon stories?

Gary: Yeah, sort of every chapter you find he’s Zelig of the book. In every chapter he kind of finds his way. There is a small Aubrey biography woven through it unwittingly, just because he is one of the more colorful characters. He kind of harkens back to a different kind of swashbuckling capitalism. Partly he enters the oil business, kind of a wildcatter, and partly he did have a very unusual role just that effectively the company he had, Chesapeake, was thought of as somewhat small, sort of volatile, high risk.

Mike: A wildcatter spirit of a company versus the more corporate people?

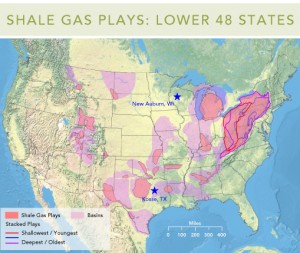

Gary: And hold onto your seatbelts when you deal with Aubrey and Chesapeake in general. When the shale revolution started ‑‑ it wasn’t really him, it was another company, Mitchell Energy that started it. So when it started, what Aubrey did was really kind of sort of start this competitive frenzy in successive basins where people would discover oil, maybe we have a shale here in north Louisiana or east Texas or North Dakota on the oil side, or Pennsylvania or Ohio. And Aubrey had thousands of guys knocking on doors, and an unlimited appetite for capital and complexity, and everything that just got billions of dollars.

Then everyone looked around and oil companies pursuing more normal course ambition ‑‑ “Well, Aubrey’s going to suck up all the opportunities!” and so he was the catalyst in these basins for this frenzy. Then ultimately, you know what happened was he kind of didn’t fully grasp ‑‑ no one did, how good this was going to be. So he ended up with a lot more gas and crashed the price of gas. So many basins worked, and successively cheaper prices, and that happened on the oil side, and then also just any companies with too much debt heading into a downturn is always going to be in trouble. He kind of got a margin call on his personal account for two billion dollars.

Mike: I should be so lucky someday. I will be so upset when I get a two-billion-dollar margin call.

Gary: That’s how much he was worth at the peak. I don’t know what the margin calls was for but my net worth went down by a couple billion dollars. Then he kind of got kicked out of Chesapeake because of all sorts of other somewhat old-school CEO perks that are sort of beyond ‑‑

Gary: That’s how much he was worth at the peak. I don’t know what the margin calls was for but my net worth went down by a couple billion dollars. Then he kind of got kicked out of Chesapeake because of all sorts of other somewhat old-school CEO perks that are sort of beyond ‑‑

Mike: Sort of pledging shares, right, for his own purchases?

Gary: More like he had the right to buy interests personally in all the oil wells Chesapeake owned, which is a thing ‑‑

Mike: I see, a conflict of interest.

Gary: Yeah, just kind of was not done that much anymore. Then he got backed by a private equity firm and they bought eight billion dollars of properties, oil properties right before the oil price collapsed. The bigger issue facing him was not really this indictment, which is somewhat on a pretty secondary issue, but really was on financial difficulties, and five or six different companies all bleeding cash, and all big debt problems.

Just sort of the world coming in ‑‑ he owned 20% of the Oklahoma Thunder and he had pledged that for a loan. I think maybe it was last weekend [September 2016] for some reason he needed to have the largest collection of Bordeaux in the world. So that’s being auctioned off now by his estate. Somewhat in bad form, and got a lot of bad publicity. He had pledged 20 million dollars to Duke his alma mater.

Mike: I read about that, that Duke said “where’s our 20 [million]?,” and the heirs didn’t find that tasteful.

Mike: I read about that, that Duke said “where’s our 20 [million]?,” and the heirs didn’t find that tasteful.

Gary: Oh, the Duke alumni, the Duke community ‑‑ just say yeah, that’s a charitable donation. It is unclear what will happen, but it is definitely a very 19th century or very early 20th century, Dreiser story of rising and falling and rising and falling.

Mike: Captain of Industry or Robber Baron type.

Gary: Outside the realms of normal corporate America or the norms of it. Obviously kind of very entertaining but did have an impact on it. He was known to be an extremely nice guy.

Mike: Presumably a gregarious salesman type.

Gary: Yeah, he wasn’t cynical. His margin call was on buying – insatiably – stock in his own company, so he obviously believed in it. He was not a dark figure but an irresponsible figure, then left a lot of obviously shareholders, partners, and everything holding the bag, based on sort of a wild irresponsibility in terms of how he built his business.

Mount Rushmore of Fracking – Lucky or Good?

Mike: What I liked about your ‑‑ on the one hand celebration of capitalism and innovation and in a sense “here’s the new shale billionaires” ‑‑ you have a “Mount Rushmore” of four of them, who rose above the others. On the one hand, we have a tradition in the United States of celebrating these people as paragons of capitalism and far-seeing geniuses, of which Aubrey is included with that, with Mark Papa from EOG and this guy Harold Hamm, and I guess George Mitchell, one of the originators of the techniques.

But then I appreciate that you also say there’s an aspect of the story which is these guys have just sort of dumb luck combined with bizarre personalities, like you’re describing with McClendon with his appetite for risk and appetite for everything ‑‑ I appreciate it. And then trying to figure out: Are these guys just beholden to their own personalities and limitations and that’s why they did these odd, risky, crazy things, which turned out to be “right place, right time,” at the right scale? Which is obviously huge they all did that.

There’s this awesome passage which I’d also like to read, which is among my favorites of the whole book, which is describing Aubrey:

“Aubrey feels sometimes like seeing the country’s best restaurant critic blissfully eating from a box of day-old donuts. People respect the critic for the sensitivity of his palate, but maybe the man just likes to eat.”

I really liked that.

Gary: That’s brilliant.

Mike: It is really. It encapsulates that we celebrate these capitalists for their amazing talent and yet I don’t know, maybe the guy’s slightly insane and just has no taste at all. It’s just awesome, but of course, I love day-old donuts too. I can relate.

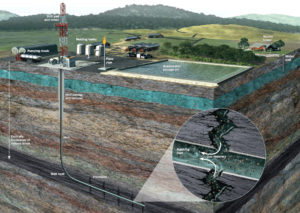

Gary: I think people in the oil business are very fond, and this is probably in any business, “My successes are because I’m smart; his successes are because he’s lucky.” Being in a business one gets a bit more color on who was lucky, who was smart. Most people are some combination thereof. But I think the thing to remember about the entire industry is before the shale revolution the US onshore ‑‑ we had a company in Corpus [Christi] working in South Texas, about drilling wells for 400,000 dollars to find 2 million dollars’ worth of gas.

Mike: Scratch and peck kind of little tiny companies.

Gary: Yeah. And anyone in the oil business, like Exxon, which looked in contempt at the US onshore business as a bunch of losers who couldn’t make it doing big international stuff in Kazakhstan or offshore Angola or Equatorial Guinea. There was a certain very admirable hustle, that kind of never-say-die that kept ‑‑ people shouldn’t have been drilling before ’98 in the US if you think about where were the best reserves of oil and gas.

It was just – globally – it was just the infrastructure wasn’t there to displace it. Then the shale revolution came and suddenly ‑‑ the amazing thing wasn’t just that actually underneath the stuff that these guys were scratching and pecking, as you say, were an amazing volume of oil and gas but actually oil and gas was a lot cheaper to extract than the stuff Exxon was doing.

Mark Papa

It’s one of these stories of “the first shall be last, last shall be first” that really came out of nowhere. And everyone got caught up in it. Then there’s all these micro stores because there’s a lot of basins that have risen. Think about there in Eagle Ford, which is the one closest to you guys. Eagle Ford now is – the most shale wells have been drilled in Eagle Ford. It’s now kind of a mature basin. It was really developed by EOG, gets a lot of the credit ‑‑ Mark Papa.

And kind of was one where it was a stealth play. And then there’s this mad rush for the Eagle Ford. Now the Eagle Ford is kind of considered well, there’s A) it’s drilled up a lot, and some of it’s more natural gas, and some of it’s more natural gas liquids, and it’s not that good. And by the way, if you go to West Texas, the Permian, there’s an Eagle Ford stacked on top of another Eagle Ford. There’s all these thousands of feet of different benches you can drill horizontal wells in.

Eagle Ford is now considered okay, a little mature, maybe some opportunities, but you’re only interested in moving back there if you can’t find anything in the Permian in West Texas and New Mexico. There’s dozens of different kinds of stories of rises and falls and the business ‑‑ there’s not just a lot of amazing oilmen who picked exactly the rise and fall correctly. There were some who were just there in a basin that ended up rising. And there are some that did guess it correctly. There are some who came in too late and ended up losing a lot of money.

Mike: There’s a bunch of things I want to follow up on that. One is the Permian which I don’t know much about but a month ago [September 2016] the general newspaper readership got a sense that Apache Energy had a huge find. I want to follow up on the “genius capitalists” of the thing.

There’s a local guy who I don’t know personally, but was celebrated around the discovery of the Eagle Ford. Suddenly this guy I hadn’t heard of before, named Rod Lewis became a known shale revolution gas billionaire. Part of his legend – and I don’t think he appears in your book, is as a very blue-collar guy checking old oil wells and then ‑‑ sudden success is always overnight and it took 20 years that we didn’t know about…

But you do describe a guy, and I don’t know if you have stories about him or his thing, but you do have a thing that sounded very similar to that, in your book. Terry Pegula, who sounds similarly this blue-collar guy in the business of helping plug old oil wells and then suddenly seems to, out of nowhere, have acquired a massive amount of leases, which is then first worth a billion and then three or four billion a couple years later. Do you know the Rod Lewis story to tell? Local people might be interested. I’ve only heard basically what I just told you.

Terry Pegula

Gary: Petro-Lewis is a very well respected company and definitely considered one of the Eagle Ford’s central private play. I don’t know his story particularly, but Terry Pegula, who now owns the Bills2 and Sabers and the savior of Buffalo was definitely almost like a hoarder of leases.

Mike: Clean your stuff out, man. We’re going to call the cops on you. He was that guy?

Gary: Yeah, and would take them from other companies with the agreement that I will plug these wells ‑‑ a natural gas well sometimes can produce for a century maybe, at very low volumes, but it gives you the right, based on the lease, to actually drill beneath it. Even if you have a well producing 50 dollars a day of stuff, it does give you the optionality ‑‑

Mike: Vertically you can go below that existing small-producing well.

Gary: Yeah. He didn’t do that on purpose. No one thought when he was hoarding these leases that there was going – Qatar was going to be in Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. He was just doing it because he liked doing it. I think also as a car dealer once said to my wife his view, “If it’s free, it’s for me.” People would just give it to him because it took liabilities off their hands. I don’t know the Petro-Lewis story but that’s one of those kind of amazing stories, sort of the wheels of markets and capitalism and fortune and luck and idiosyncratic histories that people like to wrap up sometimes in a more heroic narrative.

Mike: We love the narrative of the blue-collar guy making good. That’s a pleasing capitalist ‑‑ it’s terrible when the rich remain rich. It’s great when the poor suddenly make it rich.

Harold Hamm: Humble, but sensitive, Trump supporter

Gary: That’s why Harold Hamm, hearing him getting offended by “fracking,” he is the single person who’s gotten richest individually off the shale revolution. He is one of 13 kids, a sharecropper in Oklahoma, who barely graduated high school. Never went to college. Didn’t have shoes until he was six. A story out of a different century and now is the 70th richest man in the world. He signed a giving pledge with Bill Gates.

Mike: I think you described him getting into North Dakota because he was one of these losers who had no other chance.

Gary: Exactly. He admits it. He’s a humble guy in some ways. He kind of admits “I couldn’t afford what we were paying” ‑‑ basically you’re paying option value for leases in North Dakota.

And I heard Harold Hamm speak, and he gave a very pro-Trump soliloquy, like 45 minutes long with slides, more of a presentation. He talked about a very obscure argument. I don’t even know what happened, but Trump came to Colorado and also said basically the same thing Hillary said, which is communities should be allowed to regulate fracking in their backyard.

And Hamm’s like: “Forgive my friend Donald. He didn’t know what he was saying. He agrees with me.” Even the word “fracking.” He’s one of Trump’s chief supporters. And he made it clear that if you use the word fracking around him, the conversation is over, because it is an insulting term to describe hydraulic fracturing.

Mike: Okay, words matter and that’s a hurtful word for him.

Gary: Yes.

Mike: Okay. He sounds a little sensitive, but anyway.

Gary: You’d think 70th richest man in the world and 12 billion dollars would make you less sensitive. Apparently, that’s not the case.

Mike: Words have power and he’s a man who can be hurt by that word.

Please see related audio post (upcoming)

Part II with Gary Sernovitz – on the environmental issues of fracking

Before becoming an oil private equity guy, Gary Sernovitz was the next F. Scott Fitzgerald, and authored two novels, Great American Plain, and The Contrarians.

Please also see related posts:

Natural Gas Revolution – Corporate, Well-capitalized

Mad Max Bizarro World – South Texas

Audio Interview with Bryant on Fracking, and Regrets

Post read (195) times.

- The indictment came down in March 2016 ↩

- Just found this story from 2014 and Trump’s tweets about getting beaten by Pegula in a bidding war for the Bills. Trump, ever the petulant child. ↩