First published forty years ago, A Random Walk Down Wall Street by Burton G. Malkiel is one of those books – much like Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor – more referred to than actually read.

Malkiel’s central thesis – that equity markets are so efficient at pricing stocks relative to their risk that the vast majority of investors would do best to buy an index mutual fund rather than invest in individual stocks or buy an actively managed mutual fund – has utterly demolished the other side in the battle of investment ideas, even if the war of investment ideas rages on in the world, oblivious to the total intellectual victory of one side.

Since a majority of individual equity investors – in addition to institutional investors – do not yet embrace in practice the Random Walk’s Efficient Market Hypothesis, more should probably read this book to realize that the battle has already been decided.

Lately it does feel as if the tide is turning – as both more individuals and more institutions realize that although some individuals and some managers may ‘beat the market’ some of the time, few managers beat the market often enough to justify their fees. And further, that even if some managers did regularly beat the market in the past, it’s quite difficult to know in advance which ones will beat the market in the future. The resulting logical choice that more and more people make – despite the extraordinary marketing efforts of the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex – is to purchase index funds.

A Random Walk‘s impact

How important is Burton Malkiel and his book? One measure of his book’s impact is the index mutual fund industry.

At the publication of the first edition of A Random Walk in 1973, the ‘index fund’ did not yet exist, and instead was something Malkiel mused about:

“What we need is a no-load, minimum management-fee mutual fund that simply buys the hundreds of stocks making up the broad stock-market averages and does no trading from security to security in an attempt to catch the winners. Whenever below-average performance on the part of any mutual fund is noticed, fund spokesmen are quick to point out, ‘You can’t buy the averages.’ Its time the public could”

Shortly thereafter, John Bogle at Vanguard proposed the creation of the S&P 500 index, which became available to the general public in 1976. Malkiel became a director at Vanguard fund and may take considerable credit for the intellectual authorship of this superior idea.

The Tide is Turning

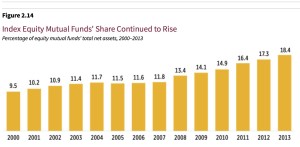

After reading Malkiel’s A Random Walk, I was fascinated to learn about the following shifts in the mutual fund landscape in favor of indexing:

For eight years in a row leading up to 2013, domestic (US) actively managed equity funds experienced net outflows, while domestic index funds experienced inflows.

Of the $167 Billion in net new money invested in mutual funds1 in 2013, $114 Billion went to index mutual funds.

As a result of these trends, equity index funds, as a share of all equity mutual funds, has hit a high of 18.4% in 2013, up in a steady increase almost every year from just 9.5% in 2000.

Malkiel’s book does not explain all of this shift, nor did it cause it, but it has provided the popular intellectual justification behind the investment of hundreds of Billions of dollars per year. That’s a pretty cool legacy that should at least be added to his Wikipedia page or something.

Great writing

Malkiel carefully navigates that difficult ridge line between technical writing that includes academic research, including probabilities and statistical methods, and fundamental security analysis – upon which he bases his ideas – and popular interpretations and advice for the average investor.

While stock prices may be random, his writing is anything but random. He’s careful and logical and subtly funny too.

I expected the academic case for the Efficient Market Hypothesis – for which A Random Walk is most famous – but I am pleasantly surprised at how practical, accessible and prescriptive the rest of the book is on constructing an individual’s investment portfolio.

How to value stocks – two ways

Malkiel posits two ways to determine the value for any stock.

Fundamental value – Benjamin Graham in The Intelligent Investor taught us the theory and technique for determining the fundamental value of securities.

In plainest terms, you have to determine all of the future cash flows of a security, and then apply the discounted cash flows formula to determine the present value of all future cash flows. The sum of all discounted cash flows equals the fundamental value of a security.

The great thing about this technique is that you can know the actual worth of a stock, for example.2

Furthermore, asset prices periodically revert back to fundamental values, so if you can do this technique you can know in a sense where prices are headed, at some point in the future.

Many investors – including probably the majority of mutual fund portfolio managers, Wall Street analysts, and stock-picking hedge fund managers – employ fundamental valuation techniques when selecting stocks. Certain bottom-up investors, also known as value investors, believe that they can achieve impressive results using fundamental valuation techniques.

Graham’s most famous student Warren Buffet seems to have done pretty well using this technique.

The terrible thing about this technique is that:

a) Its incredibly hard – ok it’s impossible – to actually know what all future cash flows of a stock will be – so we end up adopting models of the future that include substantial guesswork about earnings growth (or shrinkage);

b) The appropriate mathematical discount rate for determining the present value of all future cash flows is also always an estimate, introducing a further element of imprecision to what appeared at first to be a precise process, and;

c) Market prices can remain widely divergent – above and below – from fundamental value for long periods of time. “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent” is an old Wall Street phrase that captures just this type of problem with fundamental analysis. It’s an unfortunate but true statement that sentiment and irrational factors – the eternal struggle between fear and greed – and technical factors such as the ebb and flow of investment funds – can set the price of stocks far away from fundamental value for long periods of time.

So fundamental value techniques, explained by Malkiel as well as critiqued by Malkiel, are a commonly used technique but not a panacea for stock market investing.

Investor Sentiment – Malkiel credits Economist John Maynard Keynes as an early proponent of the truism that the combined madness and wisdom crowds – also known as investor sentiment – can carry along the price of individual stocks as well as the general level of the market, irrespective of fundamental value. Believers in the theory of investor sentiment may invest with the idea that they can anticipate future interest in a stock or in the market by understanding investing crowd psychology.

When it comes time to sell, the price of a stock will be buoyed by other believers in the ‘story’ of the stock or the market, willing to buy in at the same or higher prices. Even for fundamental value investors, an owner in equities has to depend to some extent on the future participation of others in order to receive value in the secondary market for any shares sold.

This is sometime described by the shorthand phrase ‘The Greater Fool’ theory of investing. Meaning, I don’t necessarily need to know anything about a stock’s fundamentals as long as a Greater Fool than me is willing to buy my shares when I want to sell.

The great thing about ‘investor sentiment’ investing – which by the way I would posit 99.5% of all individual investors depend on much more than fundamental value investing – is that you don’t need to do much homework or heavy math. Just get a ‘feel’ for the direction of the market or the ‘story’ of the stock, and away you go. Again, this is basically how everyone invests in stocks in practice.

I mean, do you know any non-professional stock investors who model out all future cash flows and then apply an appropriate discount to obtain a present value? No? Me neither.

The problem with investing largely on this theory, however, should be obvious for a number of reasons:

a) While irrational exuberance (and its evil twin “irrational lugubriousness”3) can dominate for some time, it’s a ridiculously blind way to invest. We all do it of course, but we’re blind. And we should acknowledge our blindness in advance.

b) Bubbles grow out of Greater Fool theory investing, and the end of bubbles is always ugly and painful.

c) Sentiment can and does change much faster than fundamentals, adding unwarranted volatility to markets as well as possibly to unwarranted activity in our own investing. We humans change our minds twice a day before breakfast and four times on Thursdays. That kind of volatility of sentiment tends to hurt our investment portfolios.

So which way of investing is right? Neither!

As investors we often adhere – at least in theory – to one of these two methods.4 But neither tends to serve us well, or well enough, to achieve an edge over any other investors.

Malkiel advances the Solomonaic wisdom5 that both theories are right, and both are wrong.

Certainly both fundamental value and investor sentiment do determine market prices in a confusing, seemingly random, combination. The problem is that with most stocks we compete with hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of extremely smart and knowledgeable investors. With so much competition to achieve the best returns for our capital, we rarely have the chance to outguess others in a profitable way.

We try and try, but as Malkiel’s and others’ academic research has shown, precious few professionals can achieve a better result than the market as a whole. As individuals we have even less chance to outperform than the professionals.

‘Tis The Gift To Be Simple

Malkiel’s famous conclusion in A Random Walk is that most people would do best by trying to simply earn the market returns of the broad market – rather than attempt vainly to ‘beat’ the market.

As the old Shaker dance goes, ‘tis the gift to be simple, ‘tis a gift to be free. The modest, simple, low-cost index fund beats managed funds most of the time, and it also beats an overwhelming majority of actively managed funds over extended periods of time.

Since all mutual funds in aggregate are made up of the entire market, logically the aggregate returns of all mutual funds will reflect the aggregate returns of the entire market. Roughly half will ‘beat the market’ in any given year, and roughly half will underperform the market. However, past performance – as the clichéd disclosure goes – does not predict future results.

With each successive year you compare actively managed mutual funds to market returns, fewer and fewer actually ‘beat the market.’

In practice this is what academic studies confirm, except for the fact that actively managed mutual funds tend to lag, in aggregate, market returns by approximately the fees they charge. Which fees tend to range from 0.75 to 1.5% of assets.

Index mutual funds by contrast tend to charge 0.1% to 0.35% fees and so tend to underperform their respective markets by a much smaller amount.

Forty years later, hundreds of billions of dollars flow into index mutual funds annually, in large part due to Malkiel’s popular presentation of these simple ideas.

Final thoughts and caveats on index investing

S&P500 not entirely diversified

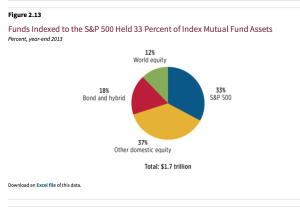

About one third of all indexed investment money currently resides in S&P 500 index mutual funds. The S&P 500 Index consists of the largest 500 US companies, which make up 75% of total stock market value in the United States. As such, this index serves pretty well as a proxy for market exposure, but investors should understand that it consists of only large companies and only US-based companies.

Investors in the most popular index fund do not get the diversification of ‘mid-cap’ or ‘small cap’ companies, many of which may ‘beat the market’ in any given year or even long period of years. Furthermore, some research suggests that smaller capitalization stocks may outperform larger capitalization stocks in the long run. This may be because smaller companies appropriately offer higher returns because they are smaller and possibly inherently riskier. I don’t think the research is definitive on this point, but at the very least investors in the S&P 500 should know that they’re only getting exposure to 75% of the US stock market, and only the biggest companies.

Perhaps more importantly, investors in the S&P500 index forgo exposure to the majority of public companies – approximately 60% – that are not listed on the US stock exchanges. S&P500 index investors miss direct exposure to the public companies of Europe, Japan, Australia, Africa, Latin America, China, and India – any of which may ‘beat the market’ represented by large cap US companies. Of course, equity markets are linked and responsive to one another, and the largest US public companies have extraordinary exposure to non-US growth, but the effects are indirect. S&P 500 index investors should know they are not as geographically diverse as they could, and probably should be.

Author Lars Kroijer argues in his book Investing Demystified, persuasively I think, that the logical approach for someone who embraces the Efficient Market Hypothesis of A Random Walk is to invest in an ‘all world equities’ index. This product exists, and offers a cheap, maximally diversified way to wholly embrace Malkiel’s approach.

Market-weighting indexes have drawbacks

The next problem with the S&P 500 index is that it is designed as a market-weighted index, meaning investors get their money allocated to the component stocks of the index in their current market-capitalizations proportion.

Here’s the problem with that. If Apple Inc makes up 3% of the S&P 500 index, and investor sentiment pushes up the value of Apple shares when the iShoe gets announced, such that the weighting of Apple becomes 3.1% of the largest 500 companies in the US, then index funds are forced to buy more Apple, to remain in line with market-weightings.

This type of forced buying acts to further push up shares of Apple. A self-reinforcing market mechanism – when buying forces more buying – creates a troubling feedback loop that probably pushes the stock away from fundamental value and possibly creates opportunities for non-indexed money to take advantage of index money.

Its not terribly hard to see how the largest capitalization stocks could be pushed to prices higher than fundamentally warranted as a result of too much S&P 500 index money for example, which would tend to dampen returns for investors in the largest capitalization stocks.6

As Malkiel describes repeatedly throughout A Random Walk, certain smart investments cease to be as smart when everybody does them. The success of the S&P 500 index mutual funds in particular may make future investing in the S&P 500 index less attractive for the purposes of achieving broad market returns.

In this case a simple solution is to diversify into a broader market index like the Wilshire 5000, or the kind of total world equities index advocated by Kroijer.

Please see related post, All Bankers Anonymous book reviews in one place!

Please see related book reviews:

The Intelligent Investor Benjamin Graham

The Signal and The Noise by Nate Silver

Investing Demystified by Lars Kroijer

And related posts:

Nate Silver on the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Lars Kroijer on Agnosticism over Edge

Post read (3428) times.

- Defined by the report as “new fund sales less redemptions combined with net exchanges” ↩

- Or annuities, private companies, bonds, longevity insurance, oil and gas leases, or income-generating real estate. If a financial instrument has cash flow, this is the way to value it. By the way, as a side note, how do I know gold isn’t a real investment? No cash flow. ↩

- Thank you. Thank you very much. In the future, when I am Fed Chairman, I will just whip that phrase out during a Great Recession to show how the market is excessively pessimistic and stocks are about to soar. Then later I will have it trademarked. Who wouldn’t buy my next book titled ‘irrational lugubriousness?’ It has a nice ring to it. ↩

- In practice, as I mentioned before, 99.5% of all individuals just punt with the investor sentiment method. ↩

- By that I mean: Split the baby in half, leaving nobody happy. ↩

- That, Alanis, is a much better example of irony than the proverbial black fly in the Chardonnay, which is really just an example of something that’s kind of a bummer. ↩