As of last week, your income taxes are all filed. Congrats! Or, like me, you got an extension. Boo!

In either case, it’s a good week to think about what our tax money bought this year. And since we’ve all been promised federal tax reform this spring or summer from a unified legislative and executive branch it’s also good to reflect on how the federal government spends our tax dollars now, and how it might spend them in the future.

In either case, it’s a good week to think about what our tax money bought this year. And since we’ve all been promised federal tax reform this spring or summer from a unified legislative and executive branch it’s also good to reflect on how the federal government spends our tax dollars now, and how it might spend them in the future.

A simple way to understand federal government spending is to compare it to a household. I don’t mean governments should be run like households – they shouldn’t – I just mean that we taxpayers can understand numbers that resemble the size of our expenditures in our own life. Otherwise you know, a billion here and a trillion there, it can get confusing.

The median household income in 2015, according to the US Census, was $55,775. With simplicity as my goal I prefer an easier, rounder number. So let’s just say instead of the median, we have $100,000 to spend each year as a household.

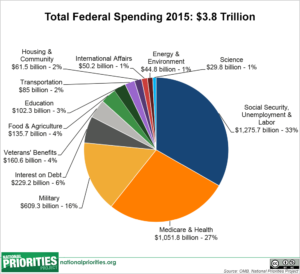

Looking at the federal government as a household with $100,000 in annual income, here’s where all the money goes, rounded to the nearest hundred dollars.

- Our federal government household paid $33,300 for a combination of Social Security, unemployment payments, food assistance, housing assistance, welfare, and labor costs. All of these are considered “mandatory” in the sense that they are promised payments, and not voted on in a budgetary process each year by Congress.

- We paid $27,400 on Medicare and other federal health-care costs. This is also “mandatory” and outside of the annual budgeting and decision-making process. The bill just comes in the mail and we pay it, no questions asked.

- Our household paid $15,800 for military expenditures. This is considered “discretionary” spending, so Congress must approve an annual budget for setting this amount.

- We spent $6,000 on debt interest, our household credit card. This is not discretionary if we ever want to be able to borrow again.

- Lastly, everything else cost $17,500 in 2015, also part of the “discretionary” part of the budget approved by Congress. That includes everything from veteran’s benefits to transportation, and from energy and the environment to education and international affairs.

So…what do we think of that? If you were in Congress looking to rein in spending as the majority party, what would you cut?

On the real political spectrum there are numerous (I won’t say there are fifty) shades of grey on the topic of federal spending. But to oversimplify into black and white shades, we could say that a prototypical left-of-center voter will say “hands off Social Security and Medicare,” while a prototypical right-of-center voter will say “hands off the military.”

And I mean, ok, sure, we all want security from foreign threats, security from catastrophic medical expenses, and security from eating cat food in our old age. So again I’m simplifying people into these two Left and Right buckets.

And I mean, ok, sure, we all want security from foreign threats, security from catastrophic medical expenses, and security from eating cat food in our old age. So again I’m simplifying people into these two Left and Right buckets.

But since entitlement reform (Social Security, Medicare, food, unemployment and housing subsidies) and Defense budgets then become sacred cows to the Left and Right, all budgetary discussion becomes really stoopid, really fast. Elected officials don’t want to turn off half the electorate by promising to actually get serious about spending cuts, so they talk about stoopid stuff.

It’s stoopid to focus on some bad art you don’t agree with funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. It’s stoopid to complain about pointy-headed liberals getting PBS funding. It’s stoopid to focus on “waste, fraud and abuse” as a real source of cost savings in the federal government. These are mere pimples on the butt of the federal government’s spending.

We need to get more like Willie Sutton and his bank robbery strategy. Why do we need to talk about cutting entitlements and defense, Mr. Sutton? “Because that’s where the money is!”

If you’re not willing to discuss cutting both entitlements spending AND defense spending then I don’t know what to tell you except you’re not invited to my birthday party and your ideas about fiscal responsibility are stoopid too.

If you’re not willing to discuss cutting both entitlements spending AND defense spending then I don’t know what to tell you except you’re not invited to my birthday party and your ideas about fiscal responsibility are stoopid too.

Having gotten that off my chest, let me say one or two sentences about why each of the three biggest sacred cows – Social Security, Medicare, and Defense – should be targets for cost-cutting at the federal level. I honestly don’t know the best way to do it. I’m just saying we could spend less on all three.

Social Security – when this program was first enacted in 1935, the average lifespan in the United States was just under 62 years. Maybe logically, people became eligible for Social Security at age 62. Would a newly-designed Social Security program set 80 as the right starting age for benefits? Maybe. Furthermore, in 1935 a 65 year-old beneficiary could expect to live until age 74, on average. Now, a 65 year-old could expect to live until age 82, on average. While that’s good news, it also means the program is far more generous, far longer, than originally intended. Sorry folks, we need to raise the eligibility age further.

Medicare – We spend 30% more than the 2nd highest-spending country-per-capita (Switzerland), and typically about double what rich countries like Canada, France, Japan spend on healthcare overall. Strangely, we have notably worse outcomes in terms of life expectancy, infant mortality and other major chronic problems such as heart disease and diabetes I don’t personally pretend to know how to cut spending and raise outcomes. And anyway, who knew health care policy could be so complicated, right? But surely we could learn a thing or two from other countries about how to bring costs down while improving health outcomes? (But please don’t call me Shirley.)

Defense – We not only pay more for defense than any other country – and three times more than #2 spender China – we pay more than the next 8 countries combined.

Paying too much for one’s military – to enforce global peace – is how empires always fall. Ask the Romans, the Spanish, and the English.

Paying too much for one’s military – to enforce global peace – is how empires always fall. Ask the Romans, the Spanish, and the English.

No more sacred cows. No more avoiding. Do the real cost cutting if you want to be taken seriously, and face the political consequences. Everything else you say about federal government cost-cutting is a joke and we’re not stoopid.

Post read (1247) times.