Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Here’s Part I of my interview with an investment consultant who charges advisory fees in an unusually (admirably!) transparent way. Click on Part II and Part III to hear Wendy and I discuss the uses of insurance, the psychology of savings, and how to get rich slow. You can read the transcript but as always I recommend the audio version highly!

Michael: Hi, my name is Michael and I used to be a banker.

Wendy: Hi, Michael. Wendy Kowalik, I founded Predico Partners. We’re a financial consulting firm.

Michael: Wendy, thanks so much for talking about that. There’s lots of different interesting things to say about your business, but I wanted to start with costs, because I think cost is one of those topics people don’t know that the most important thing to ask your investment advisor, in my opinion, is “how do you get paid?”

You have a different cost structure than most investment advisors. Can you tell me about that? and then I may jump in as well about that.

Wendy: Absolutely. What we found over the years is that most typical cost structures are built where someone brings you assets, and you’re going to charge a fee to oversee them, and invest them, and that’s how everyone gets paid. There’s a thousand different pieces of the puzzle beneath that.

What we decided to do at Predico is to go about life a bit differently. We decided we’d do an hourly charge for clients because it didn’t matter how much money you had; it was more about the time we were spending to either help you find someone to manage your money, or help you find some place to take care of it from there.

We do it based on a project fee or hourly fee.

In 2008 we had a client that had lost a lot of money, when we were in the former investment management business. And one of the things they sat back and asked was: “Do you get paid to keep me in the market or do you really believe that if I get out of the market that you could still make money and help me out?”

We decided we wanted a conflict-free answer to that question. And as we also looked at it, we had clients asking us “If our value went from 10 million to 20 million dollars are you really doing that much work for me than you were doing when it was at ten?”

The answer was no, from our perspective.

Michael: That is the main question. It’s basically as much effort to manage somebody who’s got 100,000 dollars, a million dollars, or 10 or 100 million dollars. As a manager, the scalability of charging fees on assets is so freaking amazing that it’s really unusual that someone would say I’m going to charge — you’re charging analogous to an attorney or a CPA, who would say charge me for the project by the hour, not on percentage of assets. It’s very unusual.

Wendy: Correct.

Michael: It’s almost to the point of you’ve chosen the hardest way to try to run your business, versus the scalability of “Hey, if I get a couple clients who have ten-million bucks I’m pretty much in business and I’m good.” As an investment advisor, it’s a very scalable business that way.

Wendy: That’s a very true statement. I tell clients that all the time. If you look at investment advisors they have two ways of making money. The first way is the way they’re going to market to you, which is “I make money if you make money. I grow my practice by growing your assets. That’s why we should do it this way.”

The other way is the way that most of the investment business works is I make money by getting as much assets under management as possible, so even if a market goes down, if I picked up four more clients with assets, my income has still gone up this year.

Michael: And you haven’t chosen either of these awesome ways to make money!

Wendy: for 17 years of my career I did, and I did that, and we made a really good living by managing peoples’ money, and selling them insurance. I found it wasn’t a comfortable model for me. I was uncomfortable that I was either overpaid for my time for certain clients, and underpaid at other times. I decided I just wanted to get paid for my time, in a manner that both of us could see clearly the only person writing me a check was the client. And yeah, it’s definitely a much tougher model to track your hours, but I think it’s the fairest model, and I can sleep at night when I put my head on my pillow.

Michael: A client writing a check, versus what everybody else does in the investment management world, which is I just quietly slip out a portion of your money on an annual or quarterly basis, and you never even feel the pain of losing that money. When somebody has to write a check upfront for advice they’re given, it’s just a much higher hurdle.

I think it’s sort of magical the way that most investment advisors sort of slip the money out quietly, and you never notice it.

Wendy: Very true statement.

Michael: It’s magical little part of the compensation scheme that we call investment advisory, and you’re not doing it.

Wendy: And what they teach you over time when you’re in the investment management business is “It’s going to be just like gym-membership fees. Everyone signed on to the gym, they never go, and the gym keeps collecting it.” Same thing with an investment advisor.

Michael: Neglect is a key part of a lot of business strategies, gym fees, and a lot of insurance is built around the idea of neglect. You’re not going to re-check.

On a side note, my wife and I were looking at her mutual fund choices this week, and I noticed she’s got a bunch that are fine choices in terms of risk, but they’re probably five times the fees as probably she needs. It’s been going on for ten years. I looked at it and I said, “Oh my gosh, I can’t believe you have these high-cost mutual fund fees.” She said, “You’re the one who told me to do it.” I was like “That’s right, ten years ago.” I’ve neglected for ten years to check whether she’s still in these high-cost mutual funds. There’s a lot of money involved, even at our scale, that over time those mutual-fund managers have earned, simply from neglect. I just forgot to check.

Meanwhile, I’m out there pounding the gavel for people “You’ve got to be in index funds, or lower your costs, and don’t overpay these managers.” Meanwhile, my wife’s retirement account is paying a lot of fees, and I’m the one to blame, as she pointed out correctly.

Wendy: “It is the cobbler’s kids” [“that go barefoot,” I guess] That is a very true statement It is amazing how easy it is to ignore, and it makes you realize how tough it is for clients to do it. There are many times clients say “I can’t believe I’ve let this go on. I’m so embarrassed I haven’t looked at this, or I didn’t know.” We all run into the same point. You’re busy making money for the company’s bottom line. The last thing you look at is your own bottom line.

Michael: It’s hard. I know you know — I don’t, but you’ve done this; it’s hard to get somebody to say pay me money now, upfront, for some future benefit, rather than “I will keep getting paid on a renewable, quiet, stealthy fee, year after year after year.” I admire it. I’m amazed, actually.

Wendy: Thank you. It was definitely — I was very concerned about it when I launched the model because that was what most people told me. I just don’t know that I’d be comfortable, but I found people really like the fact I have no conflict, that I can sit in a room with an investment advisor and help them interview, and ask the questions because we did sell it for 17 years. I really do know why they’re being shown a certain thing or why not. It is fascinating to see all the things that are second nature, after you’ve been in the business, that you wouldn’t even think to tell a client, and watching that evolution come out.

Michael: Somebody comes in to you and they have a modest 50,000 or 100,000-dollar portfolio versus somebody else comes in and they say “I just inherited 15 million,” are you charging essentially very similar amounts for the same service?

Wendy: As I tell everybody, we charge $250 an hour and we’ll sit down and estimate the number of hours to get you an ideal project fee. So, yeah, in answer to that question. If you want us to go through, the only difference should be if you only have 50,000 dollars and two managers, helping you review it and ask some of the questions is a lot less hours, so it should be a lot less charge than it would be if I’ve got 32 accounts.

Michael: Somebody comes to you and you’re going to put together a plan. They may certainly end up paying mutual-fund or hedge fund management fees, and then they may end up paying fees to an insurance solution on top of what they paid you. They’re not eliminating that. It’s just they’re getting that presumably without the conflict of your caring, in a sense, about who they go to. Is that accurately said?

Wendy: Right, we do not manage money so once they actually decide they want to go put that money to work, we’ll help them find somebody if they need help or we’ll review what their current investment advisor is proposing. But yes, they’re going to end up paying some form of fee. The goal is we’ve helped them negotiate those fees down as low as possible, or we help them find somebody that they feel very comfortable, and trusting that they’re in good hands if they’ve never done this before.

Please see related posts:

Do you need an Investment Advisor? And Why?

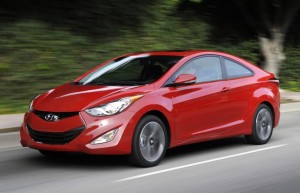

Management fees – My Hyundai Elantra analogy

Book Review – A Random Walk Down Wall Street, by Burton Malkiel

Post read (1015) times.