. Each may benefit from the other to fulfill their most urgent quest.

Julie has already eschewed the comforts of her father’s world in The Suburbs. She probably already suspects, unconsciously, that the pretensions of her young intelligentsia cohort at The Table at the LA Cafe will never fulfill her. Abdu has already dedicated uncomfortable years of his young life to attempt to gain access to the West, and away from his woebegone Village at the edge of the desert, in an unnamed part of the Arab world. He probably already suspects that time is running out on him in South Africa, that the immigration authorities will soon track him down to deport him.

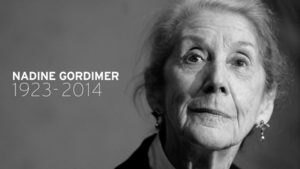

Of course a romance blossoms, despite the barriers of class, race, language, religion, and legal status. But The Pickup is no Romance. The reason we read Romance novels, I assume, is because we enjoy the fantasy of love breaking down all of the seemingly insurmountable barriers that stand between us. The reason we read Nobel Prize-winning fiction, I assume, is because we trust they tell us some higher truths about human existence. The fantasy and the truth of romance are in tension here, and Gordimer has a stubborn fidelity to truth.

Empathy

Empathy plays an interesting role in the novel. On the one hand, this is a story of emigrants and immigrants, groups deserving of the kind of empathy that novels are uniquely suited to foster. Maybe every year is the most important year to develop this empathy, but in 2016 it feels especially urgent, between the Syrian refugee crisis and the xenophobic political movements powering Brexit and candidate Trump. Gordimer published The Pickup in 2001, so clearly this isn’t the first year of our urgent need. Gordimer’s sympathetic treatment of an extended Middle Eastern Muslim family could help this need.

And yet the protagonists Julie and Abdu – for all their erotic attachment – fundamentally misunderstand one another. The shared motivating force of their lives – to put distance between themselves and the self-perceived traps of their respective families – goes unrecognized in the other. Or, if not unrecognized, at least not empathetically treated. Julie ultimately fails to see that everything Abdu does stems from his need to escape his village. Abdu cannot fathom Julie’s consistent rejection of her wealth and easy connections.

We may hope to bridge the many barriers that keep us from understanding “The Other.” Gordimer does not find that optimism overly realistic, at least for her characters. An unbridgeable distance keeps them apart.

Distance

Distance – is distance the antonym of empathy? – also plays an interesting role in the novel. Geographical distance from home, yes of course, that exists as a fact and a metaphor. Emotional distance too, as maintained by both characters. Abdu will not admit to love as a legitimate attachment while he seeks his number one goal, legal emigration. Love is a luxury he cannot afford, so he keeps reminding himself. After their first night of sex, “He resists residue feelings of tenderness towards this girl. That temptation.”

Julie doesn’t hold herself apart from Abdu, but rather her entire familial background – codenamed The Suburbs – and her entire social set – codenamed The Table, at the LA Cafe. She is from both those places, but wants more than anything to be anywhere but there. Her most desirable place on the planet, we come to learn, is as distant from her origins as possible.

Something about the voice of the novel creates distance too. The narrator adopts a particularly distant tone in the opening chapters for Julie and Abdu’s romance, with a voice reminiscent of a police procedural. “Clustered predators round a kill,” isn’t the usual opening sentence of a romance, but a crime novel. Something about the way Gordimer uses personal pronouns throughout the novel – just “He” or “She” when we expect their names, adds to the reader’s sense of distance from them and the action.

We eventually – more in the second half of the novel than the first – learn the inner thoughts of our characters. But for much of the The Pickup we only observe their actions and reactions at a distant reserve.

At the end, Gordimer offers a resolution to her characters’ situation that – if it’s not an entirely pessimistic one – is at best realistic about the possibility of bridging human gaps. Race, nationality, religion, class, country of origin, family culture – how can we expect to overcome these barriers? We need empathy, but are we wired for distance? An erotic attachment, a codependent solution we might find in the other – these are probably not in the end sufficient.

Abdu’s need to escape his village trumps all other needs. Julie’s aversion to the unconscious bourgeois life of her family repels her from not only South Africa but equally her mother’s adaptive life in California.

My weird school

I had a very personal reaction to The Pickup, based on my experience at The United World College of the American West – a high school located in Montezuma, New Mexico. Really it’s a place unattached to its nominal geography, located in what seems at first to be an impossible Brigadoon to which every student is a temporary, voluntary, emigrant. Every teenager there has chosen to be a minority of nationality, ethnicity, religion, and language, attempting to survive an unmoored internationalist, idealistic, culture. Many – probably most? – are consciously or unconsciously seeking to put distance between themselves and their home.

I kept thinking throughout The Pickup of the intensity of attachments we formed there. We marveled at ourselves, nimbly leaping over the barriers that the prejudiced adults of our homes couldn’t. We flattered each other with our openness to people who spoke and looked different from our own families. The erotic draw to “The Other” was a powerful force on campus rivaled only by the earth’s gravity.

And yet, I suspect the adults observing us also had their doubts about our lasting ability to break down these barriers. We knew too little about each others’ respective privilege. The majority of us were the verbally blessed members of The Table at the LA Cafe, smoothly critical of the old power structures. A few of us came from the easy wealth of The Suburbs, with a chance to return at any time we chose. A few even came from The Village, seekingly desperately to never return. Did we know at the time the impossible distances between us? Gordimer seems to know.

Please see related post:

All Bankers Anonymous Book Reviews in One Place

Post read (730) times.