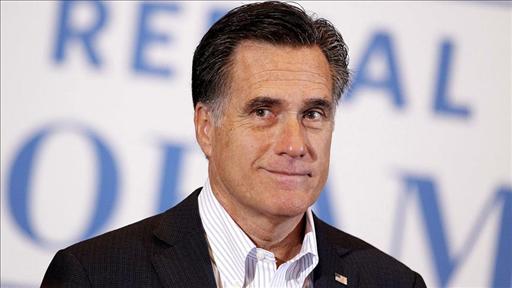

Contradicting what I wrote in my previous post about IRAs being irrelevant to upper-middle class and wealthy people, we have the curious case of Mitt Romney, who reported in his 2010 tax returns an IRA worth between $20 million and $100 million. At that level of assets, I must acknowledge he’s the exception to my rule of IRA irrelevancy for high income people.

Contradicting what I wrote in my previous post about IRAs being irrelevant to upper-middle class and wealthy people, we have the curious case of Mitt Romney, who reported in his 2010 tax returns an IRA worth between $20 million and $100 million. At that level of assets, I must acknowledge he’s the exception to my rule of IRA irrelevancy for high income people.

An IRA at $20 million to $100 million has gone from humble and homely to something quite sexy and amazing. In other words – as my wife would say – Mitt Romney’s IRA is Bradley Cooper in Silver Linings Playbook.

At first glance you may be tempted to shrug your shoulders at the size of Romney’s IRA. After all, since he’s a wealthy and successful businessman, isn’t that kind of what you’d expect? Ummmmmm, no.

It’s so incredibly unusual to amass that kind of wealth inside an IRA that I’m kind of hoping to crowd-source the answer to this mystery. I mean, I can speculate below, and I will, but I would really love for someone more knowledgeable than me to guide me in the process.[1]

Here’s why it’s hard: throughout most of Romney’s working life, the individual IRA contribution limits were $1,500 to $2,000. The limits jumped to $3,000, $4,000, and $5,000 in 2002, 2005 and 2008 respectively, but all of that is too recent to benefit from the real power of compound interest to get up above $20 million.

I am as aware of the incredible power of compound interest to grow humble seeds of capital into mighty oak trees as anyone, but the investment math involved here is not, let’s say, frequently observed.

A simple, but probably wrong, assumption

Assuming Romney was eligible to make the maximum IRA contributions from 1974 onward[2], and did so, he was eligible to contribute a total of $94,500 over the years 1974 to 2010, to his personal IRA.[3]

By applying a relentless 24.5% compounding return to each and every theoretical maximum Mitt Romney contribution from 1974 to 2010, we can in fact arrive at a total summed value of $21.5 Million.

| YEAR | CONTRIBUTION | 2010 $VALUE | #YEARS | Age |

| 1/1/1974 | $1,500 | $4,001,178 | 36 | 26.8 |

| 1/1/1975 | $1,500 | $3,213,798 | 35 | 27.8 |

| 1/1/1976 | $1,500 | $2,581,364 | 34 | 28.8 |

| 1/1/1977 | $1,500 | $2,073,385 | 33 | 29.8 |

| 1/1/1978 | $1,500 | $1,665,369 | 32 | 30.8 |

| 1/1/1979 | $1,500 | $1,337,646 | 31 | 31.8 |

| 1/1/1980 | $1,500 | $1,074,414 | 30 | 32.8 |

| 1/1/1981 | $1,500 | $862,983 | 29 | 33.8 |

| 1/1/1982 | $2,000 | $924,212 | 28 | 34.8 |

| 1/1/1983 | $2,000 | $742,339 | 27 | 35.8 |

| 1/1/1984 | $2,000 | $596,257 | 26 | 36.8 |

| 1/1/1985 | $2,000 | $478,921 | 25 | 37.8 |

| 1/1/1986 | $2,000 | $384,675 | 24 | 38.8 |

| 1/1/1987 | $2,000 | $308,976 | 23 | 39.8 |

| 1/1/1988 | $2,000 | $248,174 | 22 | 40.8 |

| 1/1/1989 | $2,000 | $199,336 | 21 | 41.8 |

| 1/1/1990 | $2,000 | $160,109 | 20 | 42.8 |

| 1/1/1991 | $2,000 | $128,602 | 19 | 43.8 |

| 1/1/1992 | $2,000 | $103,295 | 18 | 44.8 |

| 1/1/1993 | $2,000 | $82,968 | 17 | 45.8 |

| 1/1/1994 | $2,000 | $66,641 | 16 | 46.8 |

| 1/1/1995 | $2,000 | $53,527 | 15 | 47.8 |

| 1/1/1996 | $2,000 | $42,993 | 14 | 48.8 |

| 1/1/1997 | $2,000 | $34,533 | 13 | 49.8 |

| 1/1/1998 | $2,000 | $27,737 | 12 | 50.8 |

| 1/1/1999 | $2,000 | $22,279 | 11 | 51.8 |

| 1/1/2000 | $2,000 | $17,895 | 10 | 52.8 |

| 1/1/2001 | $2,000 | $14,373 | 9 | 53.8 |

| 1/1/2002 | $3,000 | $17,317 | 8 | 54.8 |

| 1/1/2003 | $3,500 | $16,228 | 7 | 55.8 |

| 1/1/2004 | $3,500 | $13,034 | 6 | 56.8 |

| 1/1/2005 | $4,500 | $13,460 | 5 | 57.8 |

| 1/1/2006 | $5,000 | $12,013 | 4 | 58.8 |

| 1/1/2007 | $5,000 | $9,649 | 3 | 59.8 |

| 1/1/2008 | $6,000 | $9,300 | 2 | 60.8 |

| 1/1/2009 | $6,000 | $7,470 | 1 | 61.8 |

| 1/1/2010 | $6,000 | $6,000 | 0 | 62.8 |

| SUM TOTAL | $94,500 | $21,552,451 |

This is mathematically possible, but highly improbable in the real investing world. Not every investment goes up in a rocky, volatile risky world. And nobody relentlessly returns 24.5%, for 36 years, in the real world. (Except, of course, Stephen A Cohen.) Or 30.7%, the amount rate of return Romney would need to achieve a total IRA over $100 million.

A slightly more realistic picture of how Romney grew his IRA

Under a more realistic set of circumstances we would assume that Romney rolled over his employer-sponsored plan like the Bain Capital SEP-IRA, which allowed for average contributions of $30,000 per year. If he regularly socked away $30,000 in his primary Bain Capital years, 1984 to 1999, he’d still have needed to average a 21% return over those 15 years to get above the minimum $20 million threshold, or over a 29% return, each and every year, to reach $100 million.

These returns are also extraordinary, but because they may have happened over a 15-year period rather than 36 year period, they become a tad more believable. The years 1984 to 1999 also coincided with an incredible bull-market run in public equity markets, which while not directly related to the private markets in which Bain Capital specialized, would tend to buoy Bain Capital’s access to liquidity, leverage, investor confidence, and exit strategies over the 15 years.

Most importantly for the IRA discussion, however, is the key point that a SEP-IRA really isn’t the humble, homely individual IRA we started out discussing. When you can contribute $30,000 per year it’s not a fair comparison to the traditional personal IRA, but rather more akin to a super-charged 401K plan.

So seemingly-homely Bradley Cooper, even when running in a black hefty trash bag and trying his best to look like the average, just out of psych lockup, slumpy, bipolar dude on lithium, was really sexy Bradley Cooper all along. (Again, the heavy editorial hand of my wife.)

But still, how could Romney earn 21 to 29% year after year after year for 15 years?

Ok fine, I’ll contribute to the speculation, which has to remain speculation because Romney never publicly explained his IRA success.

The Wall Street Journal offered a plausible explanation of Romney’s IRA success last year.

The Wall Street Journal article explains it the following way:

Bain Capital employees including Romney (as then CEO) apparently co-invested their SEP-IRAs alongside other Bain Capital funds, and probably received different classes of shares than did traditional Bain Capital investors. The different classes of shares, the speculation goes, could have systematically low values because they represented junior, or riskier, pieces of Bain Capital investments.

These systematically low-priced share-classes of the Bain Capital co-investments frequently popped in value on successful investments. When the investments worked, as they often did, these initially low-valued, risky shares offered much higher returns that we would normally find in public markets.

It sounds plausible, risky, legal, and not particularly replicable for ordinary investors.

But yes, under certain circumstances, the personal IRA can be a real cool investment vehicle.

Please see related posts on the IRA:

IRAs don’t matter to high income people

The magical Roth IRA and inter-generational wealth transfer

The 2012 IRA Contribution Infographic

[1] I am, like all non-wealthy Americans, just a temporarily embarrassed millionaire. If some helpful reader would share the Romney methods we would all be grateful, especially me.

[2] This assumption is unlikely to be true, since he was in a combined Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School program in 1974 and 1975 and might not have had any, or sufficient, income in those years as a student. But it is possible, so I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt.

[3] This $94,500 includes the ‘catch-up’ amounts he became eligible for, starting in 2002, for being over age 50.

Post read (14535) times.